Gor (1987) -***

Gor (1987) -***

Some authors, especially among those with pulpier sensibilities, don’t so much write as vomit their ids directly onto the page. Take for example Laurel Hamilton, John Ringo, and perhaps most notoriously, John Norman. Norman is an odd man to say the least. I mean, how many college philosophy professors do you know whose sideline gig writing paperback-original science fantasy novels inspired a whole real-world subculture of lifestyle BDSM types? The truly mad thing is that the more you know about Norman and his nonfiction writing, the more it almost makes sense for his fiction to have that particular impact. As a philosopher, Norman’s main concern is that perennially popular fool’s errand, attempting to derive a moral system for humans from the manifestly amoral realm of nature. Such efforts always seem to lead people into all sorts of silly essentialist positions, as if humans were no more variable and no more capable of modifying their own behavior than skinks or katydids, and Norman is no exception. He’s also a Nietzschean at heart, so his thinking tends toward a contradictory tangle of radical individualism focused on freedom from institutional interference on one hand, and on the other, the lazy reification of supposedly “natural” hierarchies that conveniently put people like him at the top. He shares some of Nietzsche’s contempt for women, too, but Norman’s is a smugly affectionate contempt that, depending on your tastes, may seem either more or less obnoxious than overt and honest misogyny. At pretty much every opportunity, Norman can be counted on to spout off about women’s innate craving for submission to a masterful man, and just in case it wasn’t sufficiently obvious that this element of his philosophy grows directly out of his personal sexual predilections, he considerately laid it all out for us in his 1974 erotic manual, Imaginative Sex. (My younger readers may not realize what a big deal sex manuals were in the 70’s; I say again that those were very strange times.) Imaginative Sex wasn’t subtitled Better Living Through Rape and Power Fantasies, but it might as well have been— and all 53 of the roleplay scenarios it contained were femsub scenes (to use terminology that hadn’t been invented yet when the book was written). Now I’m in absolutely no position to pass judgement on anybody else’s sexual fantasies. In fact, I believe it’s unethical to do so, since nobody can really help what turns them on. But neither do I conflate what makes my dick hard with a rational basis for a just and well-ordered society. John Norman does, at least if his writings and statements in interviews can be taken at anything like face value, so maybe it’s no wonder that some subset of his fans would develop into the fetish-sex community’s equivalent to Randroids and Lyndon LaRouche cultists.

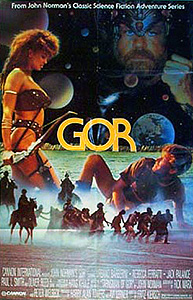

Of course it stands to reason that a philosopher who was also a sci-fi writer would use his fiction as a showcase for his ideas about the Way Things Ought to Be. What makes Norman so much more interesting than, say, Ayn Rand (despite his espousal of an ideology every inch as horrifying as hers) is the setting he chose for that showcase— Gor, a barbarous planet that shares Earth’s orbit on the opposite side of the Sun, ruled over by a race of nigh-omnipotent insects who use their super-science to keep the human population at the social, cultural, and (with a few exceptions) technological level of the early Iron Age. Imagine your most annoying Libertarian Facebook friend writing erotic John Carter fanfic, and you’ll be close to the tenor of the Gor novels. Or at any rate, you’ll be close to the lunatic self-caricatures they eventually became. The first few books, written in the late 1960’s, are actually pretty engaging fantasy adventure yarns, with just enough darkly kinky sex to set them apart from their antecedents of three and four decades past, and their viewpoint character is an Earth man who is appalled at the way of life in Norman’s utopia, even as he gradually yields to its pull upon some atavistic layer of his personality. Their emphasis is less on captivity, rape, and sex-trafficking than on barbarians riding into battle on the backs of giant, man-eating eagles. In short, those first few Gor books would have made an excellent basis for a 1980’s Conan the Barbarian cash-in— so inevitably, the Gor movies we actually got were written by people who never bothered to read the source material, and were shot by Italians with no money for giant eagles, dinosaurs of burden, or insectoid demigods. And incredibly enough, Gor and Outlaw of Gor didn’t even deliver the sleaze that had long since become the novels’ reason for being by 1987, despite the involvement of international sleaze-master Harry Alan Towers as producer.

Let’s begin with a few words about our hero, Tarl Cabot (Urbano Barberini, from Demons and Opera). In the first book, Tarnsman of Gor, he was basically a clever rogue who faked his way into an associate history professorship at a small New England college because he couldn’t think of anything he especially wanted to do with his life. His bizarre first name was a clue to the history of his largely unknown father— a John Carter-like adventurer who apparently was taken to Gor and back several times before settling permanently on the alien world. In Gor, however, Cabot is just some schmuck, and nobody even seems to notice that he’s the only person named “Tarl” on the entire planet. Cabot does still teach a college class for which he has no apparent qualifications, although I’m hard pressed to tell you what its ostensible subject might be. The one time we see him in mid-lecture, he’s blathering about Gor, the hidden Counter-Earth which he has no reason to suspect exists, and of which subsequent action will suggest that he’s never heard. Towers and fellow screenwriter Rick Marx have also invented for Tarl a fickle and fairly awful girlfriend (Ann Power), along with a rival for her affections (Arnold Vosloo, of Steel Dawn and Darkman II: The Return of Durant). This Tarl-Beverly-Norman triangle feels like something out of a teen sex comedy, and seeing it played out by characters who are supposed to be adults is just freakish.

Anyway, Beverly was supposed to go on a camping vacation with Cabot over spring break, but she has changed her mind on the completely reasonable grounds that camping vacations are pure misery for civilized people. Cabot goes it alone, but crashes his car en route to the mountains. That’s when his ring— a souvenir from the father he never met, whom the movie will never again mention— teleports him to Gor for no fucking reason. I have to assume that this is because there was no money in the budget for him to be abducted by a UFO for reasons that are hinted at but not explained until the second sequel. I’m honestly not sure which of those two plainly sub-optimal approaches is superior.

Cabot arrives on Gor just in time to witness the sack of the city of Koroba by the armies of Sarm (Oliver Reed, from Severed Ties and Night Creatures), the self-styled Priest-King of Gor. Sarm’s object is to unite the entire planet under his rule, and his strategy for doing so is to seize the Home Stones of all the free cities. In the books, the Home Stones are tied in with all sorts of world-building stuff, including some fairly persuasive history and sociology. Here, they’re just generic talismans that are important because the script says they are. The central point remains the same, though. Without his city’s Home Stone, Marlenus (Larry Taylor, of The Wife Swappers and This, That, and the Other) will lose his legitimacy as ruler of Koroba, and his demoralized people will bow down to Sarm instead. Unless, that is, there remains someone close to the throne but not on it to serve as the nucleus of a resistance movement untainted by the disgrace of losing the Home Stone. With that in mind, Marlenus has sent his daughter, Talena (Rebecca Ferratti, from Cheerleader Camp and Embrace of the Vampire) away from the city in company with a warrior called Torm and an advisor whose name I didn’t catch, neither one of whom were deemed important enough to merit mention in a credit list that includes entries like “Feast Master” and “Hooded Women.” Sarm, however, notices Talena’s absence when he tours Koroba’s conquered citadel, and he dispatches his son, Sarsam (Chris du Plessis), with a contingent of soldiers to hunt and collect her. Those men happen to find Cabot as well as their real quarry, to say nothing of a sizable body of Koroban refugees, and in a stroke of outrageous good luck, Tarl manages not only to defend himself against Sarsam, but to kill him.

Cabot’s life becomes very complicated after that. Witnesses on both sides of the fight assume that he is some sort of wandering hero who has pledged himself in opposition to Sarm’s tyranny, essentially forcing him to become just that. After all, Talena and her rebels are the only thing standing between Cabot and Sarm’s army, which as you might imagine now has special instructions to kick the ass of that guy who killed Sarsam extra-hard. So Tarl somewhat reluctantly joins Talena and her escort on a trek across the desert toward the Sardar Mountains, where Sarm makes his home. Their object is to steal back the Home Stone of Koroba and to free Marlenus from captivity. Along the way, Torm and Talena instruct Cabot in the Gorean martial arts, and the rebels acquire a new ally in the dwarf Hup (Nigel Chipps), who claims to know a secret route through the mountains and into Sarm’s capital. They also acquire a new enemy in Surbus (Paul L. Smith, from Pieces and Dune), a violent outlaw who hates Hupp for reasons that are never explained, and who furthermore thinks Talena would make a fine addition to his harem. Meanwhile, it comes out that a mystical interaction between Tarl’s ring and the Home Stone of Koroba may have the power to return him to Earth, giving him a reason to resist even after Sarm changes tactics, and starts trying to corrupt Cabot directly instead of dispatching hordes of goons to out-fight him.

In case this wasn’t obvious from the introduction to this review, let me state for the record that I’m a somewhat grudging fan of the Gor books, at least the few I’ve managed to track down thus far. I appreciate them as eccentric variations on the “planetary romance” genre of science fantasy, as uncommonly imaginative soft smut, and perhaps most of all, as the inadvertent self-psychoanalysis of their fascinatingly crankish and peculiar author. And so I’m forced to agree with Norman’s own assessment of Gor and its sequel: “I am pleased that the two films were made. It would have been even better, of course, if they had had anything to do with my work.” On the other hand, most people watching Gor probably never wanted a BDSM barbarian movie in the first place, and will be relieved that nothing recognizably Norman’s survived the translation from print to celluloid. This is one of those times when evaluating the film requires forgetting about the supposed source material, because nothing has been carried over except for a few concepts and character names— the latter of which can’t even be counted upon to refer to people analogous to their original bearers. Sarm, for example, was basically a giant praying mantis in Norman’s telling, while the character who best corresponds to the movie’s Sarm is the books’ Marlenus!

The most entertaining things about Gor can all be implied simply by mentioning the company that put up the bulk of the money for its creation, the infamous Cannon Group. It’s a moderately well-funded movie that still looks cheap and shoddy, not least because of production design that never really adds up to any overarching esthetic. Many of the props, set elements, and costumes look as if they were recycled from some other production. Take the weapons, for example. Perhaps half of them are typical of 80’s barbarian movies generally, on par stylistically and in standard of construction with those of Conan the Destroyer. A few, though, are far more fancifully designed, and would be better suited to something like Masters of the Universe— or to a Gor movie that was serious about adapting the novels. Then there are some really crude and clunky ones that look like they were made for a stillborn sequel to Ironmaster. There’s no apparent pattern to the mixing and matching, no sense that the different weapon styles reflect different cultures with different sensibilities or different levels of technological advancement. The same could be said of the costumes for everybody other than Sarm and his soldiers, which display little commonality beyond a reliance on leather and a most unfortunate devotion to loincloths with that thong-point-three level of butt coverage which never does any favors for even the most perfect ass, male or female. And the sets often don’t even make physical sense, with the worst offender being the village where Cabot and company meet Hupp and Surbus. It’s a tent city in the middle of a flat, sandy desert, right? So how the hell is its tavern an enormous, Bronson Canyon-like cave? Wouldn’t a thing like that be visible in some of the long-range establishing shots?

Similarly typical of Cannon— and especially of Cannon’s international productions— is the lunkheaded screenplay by Rick Marx and Harry Alan Towers (the latter writing under his “Peter Welbeck” pseudonym). Rick and Harry don’t waste any time in showing us what they haven’t got; the very first words we hear are Cabot’s interminable, rambling lecture about Gor and his dad’s ring: “So… This stone— this glowing gem, found hundreds of years ago in a Hibernian cavern— possesses a key to another world, known as a Counter-Earth, called ‘Gor.’ How the stone works, and the circumstances that govern its power, and the nature of Gor itself, are yet undetermined by modern science.” Then we get college professors behaving like B-movie teenagers, setting up the inevitable moment when Cabot returns to Earth after his trans-dimensional adventure endowed with the strength and courage to punch Norman in the nose. The writing does not improve when the setting shifts to Gor, but at least there we’re in the comfortable company of well-worn barbarian movie clichés. You know the ones: arbitrary quests with arbitrary sub-goals, arbitrary attacks by arbitrary enemies, arbitrary catfights at arbitrary moments, and so on.

The true joy of Gor, though, is Oliver Reed’s Sarm. His character design, to begin with, is almost as confrontationally ridiculous as that of Kadar, the evil warlord in The Barbarians; given that both films were made for Cannon International, the resemblance is probably no coincidence. Sarm’s costumes could not possibly be any less flattering to a man of Reed’s age and physique, proudly exposing acres of swelling paunch and sagging pecs, and drawing attention to shoulders that are perhaps no longer as broad and straight as they once were with a succession of ill-fitting ornamented collar-contraptions. His headgear is a marvel to behold, ranging from heavy crowns that look like he’s wearing them upside down to a horned-and-winged bronze helmet suggesting that King Ghidorah has come in for a landing on Sarm’s head. Even the red-gold dye-job the makeup department has given Reed’s hair and beard might as well have been calculated for absurdist effect. Then, once again, there’s the dialogue, which in Sarm’s case aims for Shakespearean villainy, but comes out closer to the Al Adamson variety. And of course there’s the inescapable sense that the details of Sarm’s actions never quite square with his stated aims. Take, for example, his orders that until Sarsam’s killer is found, a hundred of Koroba’s people— “men [Shatner pause], women [Shatner pause], and children”— are to be tortured in his dungeons. What’s the point? I mean, it might make a certain amount of sense if Sarm expected the friends and relatives of his victims to squeal on Cabot, and Sarm admittedly has no way of knowing that the man who killed his son was not of Koroba in the first place, but there’s no indication that he has any such aim in mind— and even if he did, he promptly goes back to the Sardar Mountains, where no Koroban stool-pigeon could get in touch with him anyway! And yet despite all that, Reed commits to this role with every brandy-sozzled fiber of his being. The funny thing is, that commitment comes in two sharply demarcated flavors. Early on, we get Serious, Intense Ollie, the one determined to treat Gor as if it were worthy of his talents in the best mid-century British tradition. In those scenes, Reed underplays nearly to the point of whispering his lines, creating a nicely counterintuitive impression of Sarm as a mild-mannered monster. Then, in the second half of the film, by which point Reed presumably has an extra payday or two’s worth of booze in him, he seems to realize what he’s really signed on for, and says, “Oh, fuck it— RELEASE THE HAM KRAKEN!!!!” The contrast between the two halves of the performance is shocking. Even Sarm’s hilariously cursory death scene leaves no adjacent fragment of scenery un-chewed. It would be dispiriting to contemplate Reed’s absence from the sequel if I didn’t already know that the villain in Outlaw of Gor was to be played by Jack Palance.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact