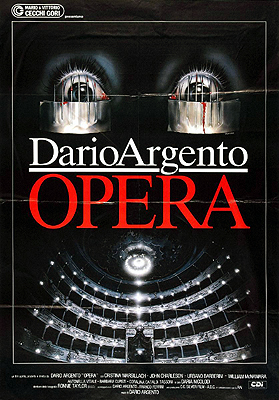

Opera / Terror at the Opera (1987/1990) **

Opera / Terror at the Opera (1987/1990) **

The Phantom of the Opera was an important part of my earliest development as a horror fan, but in a rather strange way. TV never played silent movies in the 70’s or early 80’s, so it wasn’t until my family acquired its first VCR circa 1986 that I had an opportunity to see the film itself. I read a lot of books on horror and monster movies when I was a kid, though, and back then, those could just about be counted on to feature a still or two of Lon Chaney Sr. in his Phantom makeup. The only thing scarier (which you could also just about count on seeing in those old books) was a shot of Max Schreck from Nosferatu, and thus did those two antiques join the very first list of “I have to see this one day!” movies that I can ever recall forming. A predictable side effect of all that was to make me a lifelong sucker for pretty much any riff on the Phantom of the Opera premise. The Phantom of the Opera in a rock club? In a shopping mall? On the condemned back lot of a movie studio? Sign my ass up! Gods help me, I’ll probably even get around to the one with Gerard Butler belting out Andrew Lloyd Webber drivel like he’s trying to pick a fight with it in a Waffle House parking lot one of these days. Similarly, I got more excited than I normally do about Dario Argento films when I learned that one of his 1980’s gialli was basically The Phantom of the Opera if Erik was a Black Glover. But although I know by now not to trust Argento fans too far when extrapolating my own likely reaction to his work, Opera’s reputation as the director’s last true masterpiece certainly made it sound more promising than his direct Phantom of the Opera adaptation, which even his most ardent defenders usually count among his worst films.

Marco (Ian Charleson, from Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes) isn’t, strictly speaking, in the opera business. A moderately notorious director of horror movies, he has somehow found himself helming a new production of Giuseppe Verdi’s Macbeth nonetheless. Unsurprisingly, Marco’s instinct is to shake things up, and his take on the material is looking more like something that flops expensively on Broadway than any of the usual fare at Milan’s Teatro alla Scala. (The actual shooting location for the opera scenes was the Teatro Regio in Parma.) The costumes resemble leftovers from Throne of Fire. The three witches are constantly gyrating nude girls, seen only in silhouette behind backlit scrims in a trio of alcoves above the main stage. There’s more special effects trickery than traditional stagecraft in the design and construction of the sets (which rather put me in mind of The Barbarians, while we’re comparing Marco’s Macbeth to junky Italian sword-and-sorcery flicks). And the cast must contend constantly with an ungovernable horde of ornery, scene-stealing ravens, which are supposed to provide ominous atmosphere, but have merely sown chaos thus far. Well, soprano diva Mara Czekova (this part was supposed to be played by Vanessa Redgrave, of all people, but it got reduced to a POV cam and an angry voiceover when she backed out at the last minute) has had enough, do you hear? She’s going home, and she isn’t coming back unless and until Baddini the producer (Antonio Iuorio, of Ubaldo Terzani Horror Show and Diabolik) pulls the plug on all this foolishness to put on a real opera! Nor is there any practical possiblity of winning the star back, because she’s struck by a car and badly injured while storming out of the theater. It’s nothing life-threatening, but that hit-and-run asshole left Czekova with way too many broken bones to go treading the boards again anytime soon.

Czekova’s misfortune is big news for her understudy, an orphaned singer scarcely out of her teens by the name of Betty (Collector’s Item’s Cristina Marsillach). Strangely, though, she hears it neither from Baddini, nor Marco, nor even her agent, Mira (Daria Nicolodi, of Creepers and Shock), but rather from a raspy-voiced stranger who calls her on the phone to congratulate her, then immediately hangs up. And by the time the aforementioned trio do get through to her a little while later, Betty is decidedly conflicted about the prospect of stepping into the role of Lady Macbeth. On the one hand, it is undeniably the opportunity of a lifetime. But everything that makes it so can also be read as a chance to fuck up in ways that could wreck her career at the starting gate— and everyone in the theater business knows that Macbeth is a bad-luck play! Marco is supportive of Betty’s fears, but confident in her abilities. Mira makes clear her opinion that the girl would have to be fucking crazy to let such a stroke of fortune slip by. And Baddini quite simply won’t take “no” for an answer. In the event, Betty’s debut as Czekova’s replacement is much better received by audience and critics alike than the play as a whole. She even has an admirer— Inspector Alan Santini (Urbano Barberini, from The Black Cat and Gor), of the Milanese police!— drop by after the show to give her a bouquet of flowers.

None of that is to say, however, that opening night went off without a hitch. Indeed, there was an alarming incident in the middle of Betty’s first solo, in which part of the lighting rig fell from its perch beside one of the fifth-tier balcony boxes, and crashed to the floor just behind the rearmost row of seats. And although no one was hurt down there, the whole thing was set in motion when one of the ushers confronted a prowler inside the box in question. It was their struggle that knocked down the lights, and the usher was stabbed to death. That’s what brought Santini to the opera house in the first place, overseeing the delicate business of conducting a crime-scene investigation during a performance without touching off a counterproductive panic among the spectators— one of whom, after all, might have been the culprit. Santini’s sleuthing has come up bust so far, but the moment Betty gets wind of the murder, she starts thinking about the anonymous weirdo who called her the other night, and about the equally anonymous driver who sped off after running down Mara Czekova. Betty is also quick to recognize that a sufficiently suspicious person— a police inspector, for example— might interpret those three data points as a finger of guilt pointed at her, and she takes the earliest opportunity to split the opera house before Santini comes round again to ask her any questions.

That opportunity is provided by Stefano (William McNamara, of Surviving the Game and Copycat), a stage hand who’s had a thing for Betty since long before she got promoted from understudy to star of the show. The pair withdraw to his freakishly luxurious apartment, where their attempts to do what comes naturally to 20-year-olds alone together are thwarted by some deep-seated hangup that the girl has encountered before with other would-be lovers, but has never been able to explain even to herself. The kids’ romantic evening is about to go even further awry, too, because Betty’s #1 fan has followed them. When Stefano gets up for a bathroom break, the Black Glover makes his move. Seizing Betty, he ties her to a pillar, and outfits her with both a gag and a diabolical contraption of sticky tape and sewing needles that prevents her from closing her eyes without poking her upper lids full of holes. Thus restrained, she has no choice but to observe every horrid moment as the killer goes to work on Stefano. On the upside, the circumstances of this crime can’t plausibly be taken to implicate Betty, and would therefore tend to exonerate her of any involvement in the two at the Teatro alla Scala. But for all that she was forced to watch, Betty can’t tell Santini what the perpetrator looked like, because he wore a featureless black mask throughout. The most disturbing aspect of the experience, though, might be its eerie familiarity. Although Betty has no conscious memory of any such thing, she has a nagging sense of having been a spectator to some similar atrocity during her earliest childhood. That’s way too distressing a piece of information to tell Santini, even if it might make the job of catching the killer easier. The only person Betty trusts enough to hear that confidence is, oddly enough, Marco, to whom she begins growing markedly closer after that.

At this point, it’s worth asking just what the killer’s game might be. Taking out Mara Czekova to clear the way for Betty’s ascent is only to be expected; that’s what Phantoms of the Opera do. Stabbing the usher, meanwhile, was in some sense a defensive action, insofar as he was trying to prevent the killer from witnessing Betty’s hour of triumph. And killing Stefano could be interpreted as the elimination of a rival, if again we extrapolate from the motives and behaviors of past Opera Phantoms. But making Betty look on while he took the boy apart— what the hell was that about? Well, remember that our Black Glover set all this in motion because he wanted to see the singer perform. Having watched her strut her stuff on the theater stage, and found it to his liking, he returned the favor by putting on a show for her, doing the thing that he’s good at. In truth, there’s a bit more to it than that, as Argento has already hinted with Betty’s memories of memories, but the essence of it all is still the killer seeking to establish a relationship of reciprocal exhibitionism. Nor is he going to content himself with a one-night-only booking. So long as he’s in a position to notice Betty interacting with other people— Marco, Mira, Giulia the wardrobe mistress (Coralina Cataldi-Fassoni, from The Devils of Monza and Demons 2), whoever— Betty’s #1 fan won’t ever run out of stages on which to play. The mere fact of the killer treating his crimes as a form of performance art is likely to make him difficult to catch, too. After all, people putting on a show will go to every practicable length to make sure it comes off without a hitch. The Black Glover makes a serious mistake, though, with one of his more impulsive acts of violence. While helping himself to a souvenir from one of Betty’s costumes in the backstage area where Maurizio the raven-wrangler (Maurizio Garrone) keeps his birds between shows— and going unmasked while he’s at it— the killer gets into an altercation with several escapees from the big cage, and slays them in a fit of pique. Corvids never forget a face, even when it belongs to a human. And they never let go of a grudge, either.

Opera was, to a certain small extent, autobiographical. In 1985, Dario Argento was inexplicably attached to direct a production of another Verdi opera, Rigoletto, at the Sferisterio amphitheater in Macerata. He and the theater’s management did not see eye to eye on much of anything (small wonder, that— among other things, Argento got his William Castle on, proposing to rig the seats with electrodes in order to shock the audience in time with the lightning flashes in a thunderstorm scene!), and the world would ultimately be denied the improbable spectacle of the Four Flies on Gray Velvet guy directing Verdi on a 160-year-old stage. So when Mara Czekova and the theater critics berate Marco as a boor and a dilettante, that’s Argento getting up in his feelings over the opera establishment saying much the same about him.

For most of its length, I was really digging Opera. Indeed, right up until the first time it seemed to be ending (and fucking well ought to have), I was ready to proclaim it Argento’s best pure giallo, or at least the best one that I’ve seen so far. It’s every bit as stylish as his better-known films from the preceding decade and a half or so, and since it also carried the biggest budget of the director’s career to date (seven billion lire— about $5 million at the 1986 exchange rate), he was free to seek out images that either had never been cost-effective before, or had been out of his reach altogether. In the former category, consider the recurring transitional device of a closeup on a human brain (presumably the killer’s), photographed to resemble the surface of an alien planet. It’s nifty, and it adds significantly to the mood of the film, but it’s nothing that anyone would bother doing unless they had money to burn. The most striking example of the latter, meanwhile, is the climactic raven attack in the theater auditorium, shot from the perspective of a bird on the wing. That sequence reportedly consumed a billion lire all by itself, but it was well worth the expense; there’s nothing else like it in any giallo of my acquaintance. Meanwhile, we have all the expected Argentisms: the keen eye for shooting locations, the masterful use of the widescreen frame, the downright balletic depiction of acts of extreme violence. There’s a sequence in which someone gets shot through the eyeball while peering through an apartment door’s peephole that rivals anything Lucio Fulci ever inflicted on the human eye, and that business with the tape and the needles is just brilliantly sadistic. (Supposedly, Argento thought of the latter gimmick in response to his annoyance with viewers who closed their eyes during his meticulously crafted murder scenes.) This sort of thing is why we put up with Argento’s inability to string two paragraphs of story together in a way that makes a lick of sense, so having him in such rare form ought to make Opera a film not to be missed. And maybe better still, Opera even mitigates its creator’s total incompetence as a constructor of murder mysteries by positing a scenario in which the killer’s identity per se doesn’t matter, and by wasting no time whatsoever in pursuing the answer to that question.

Alas, though, Argento gotta Argento— and when the time comes, he Argentos so fucking hard that it just about wrecks the whole film. I mentioned before that Opera pushes on past what ought to be its ending, but simply to say that doesn’t begin to convey how much damage it inflicts upon itself by doing so. You see, the false ending is just about perfect, whereas the true ending is misguided in every possible way. You know how you can never kill a slasher just once, even in a movie without any sequels? Well, that applies to Betty’s #1 fan, but in this case, it doesn’t just mean that he stands up again to resume the attack after getting stabbed in the throat or whatever. No, Opera’s Black Glover finds a bullshit escape hatch for being blown the fuck up and burned to a crisp. And his return to action occurs not in the heat of the climax, but weeks if not months later and 100 miles away, when he follows Betty and Marco to Switzerland to harass them some more. It’s as if Halloween II had a drastically truncated version of Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers grafted to its ass as a miniature fourth act. What’s more, this deformed Siamese twin of an auto-sequel spends much of its time teasing an even dumber twist, which Argento evidently intended to use for real at first, but turned away from before it could be committed to film. It’s ruinous. Just ask Daria Nicolodi: “The movie was good, but I didn’t like the ending— and I still don’t. I think it could have stopped before the Swiss nonsense.”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact