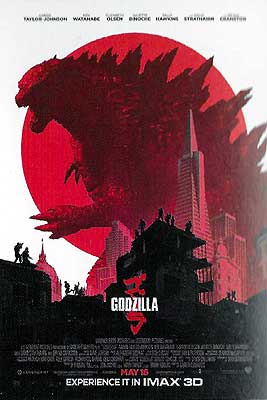

Godzilla (2014) ***½

Godzilla (2014) ***½

Remember the time a bunch of Americans (okay, fine— a bunch of Americans, a German, and a couple of French guys) made a Godzilla movie, and it stank up the place so badly that Toho, which had made a big deal about getting out of the Godzilla business only three years previously, felt compelled to get back into it to reclaim the franchise’s honor? Well, I can assure you that every serious kaiju eiga fan remembers it very clearly. That’s why there was so much trepidation and rampant negativity when word got out that Legendary Pictures and Warner Brothers were teaming up on a new gaijin Godzilla. We were afraid it was going to turn into an encore performance of the Dean and Roli Show. So it pleases me to report that the worrying was largely unnecessary. The Legendary/ Warner Brothers Godzilla isn’t just an improvement over the Tri-Star version, nor even just a worthy continuation of the Japanese kaiju tradition. This Godzilla is actually good enough that only the original Godzilla: King of the Monsters/Gojira is plainly superior, although the best of the second-tier Toho Godzilla movies (Godzilla vs. the Thing, Terror of Mechagodzilla, maybe Godzilla vs. Biolante) give it stiff competition.

One of the best credits sequences I’ve seen in ages knits together stock footage of 40’s and 50’s nuclear weapons experiments into a story that we can follow only loosely for the moment. It’s obvious enough, though, that what’s happening is of great importance to what will come later. Something about a shadowy government-connected organization called Monarch and a creature living in the Pacific Ocean so huge and terrible that nothing short of an H-bomb stands any chance of killing it. Then a caption informs us that the year is 1999, and we join a light helicopter bearing Monarch markings as it sets down at the site of the Universal Western Mining Company’s newest venture in the Philippines. Evidently there’s been a minor but very strange disaster. As a Universal Western aparatchik explains to Monarch scientist Dr. Ishiro Serizawa (Inception’s Ken Watanabe) and his assistant, Vivienne Graham (Sally Hawkins), the company was setting up for an exploratory dig based on Geiger counter readings hinting at a massive uranium deposit. Just barely had the first pickaxe swung, though, when the pileup of heavy machinery on the surface collapsed what turned out to be the ceiling of an uncharted cavern system. By the time the mess was more or less cleaned up, the radiation signature that led Universal Western to the spot in the first place had inexplicably tapered off to practically nothing, but that was only the beginning of the weirdness. Down in the deepest, most inaccessible part of the caves, the miners found the fossilized skeleton of some immense, serpentine animal. Nobody’s ever seen the like of it, and it’s much too big to be a dinosaur. If it were my discovery, I’d christen the species Jormungander sacrifaeces, translating into Latin the first thing I blurted out upon seeing it. Also, the last of the radioactivity that got the company prospectors’ hopes up happens to be concentrated in those ancient bones. Then there are the things Serizawa and Graham find inside the skeleton, a pair of… egg cases? Cocoons? Something like that, anyway. And unlike the Midgard Serpent, they appear to be alive and recently alive respectively, sustaining themselves on the radiation from the monster’s petrified carcass. The most important point, however, is that the non-living pod is non-living because whatever was inside it has hatched. And to judge from the trail it left behind as it slithered off into the ocean, it’s pretty monstrous itself.

Meanwhile, in Janjira, Japan, expat Americans Sandra (Juliette Binoche) and Ford (C. J. Adams) Brody are trying to throw a low-key surprise birthday party for Joe Brody (Bryan Cranston, from John Carter and Total Recall), Sandra’s husband and Ford’s father. It isn’t going very well. The adult Brodys are both engineers at the new Janjira nuclear power plant, and Joe is so busy worrying about a series of peculiar readings on the plant’s seismograph that he’s forgotten it even is his birthday. Joe never does put down his cell phone before Ford has to catch the bus for school, and only during the car ride to work does Sandra finally get a word in edgewise to chide him for his excess of professional focus. Of course, Sandra would probably be just as preoccupied if she had answered the call about those readings. They sort of look like the aftershocks of an earthquake, but the intervals between them are too regular, the waveforms repeat themselves too precisely, and there’s no clear epicenter to the phenomenon, almost as if the source of the tremors were in motion. Oh— and they’re getting steadily stronger, too. Joe has just given the order to shut down the reactor for safety’s sake when a tremor hits from what must be directly under the plant, and all the electronics in the control room go haywire until the backup generators come online. At the same moment, a core breach catches Sandra and her work crew down in the guts of the plant. Joe has no choice but to push the button sealing them in with the resulting cloud of radioactive steam himself. There’s no time for mourning now, either. The whole plant is falling down around Joe’s ears, and the entire town of Janjira will need to be evacuated before the place blows sky high.

Fifteen years later, Ford (now played by Aaron Taylor Johnson) is a bomb-disposal expert in the US Army with the rank of lieutenant, married to a nurse by the name of Elle (Elizabeth Olsen, of Silent House), and the father of his own young boy (Carson Bolde). Joe, meanwhile, is still in Japan, where he’s traded in his old career as a nuclear engineer for the more exciting lifestyle of a full-time conspiracy crank. With his scientific expertise, he saw at once that the official explanation for the Janjira disaster was fishy as hell, and he’s spent the whole time since that day trying to figure out what really happened. In fact, not five hours after Ford comes home from his latest tour of duty in Afghanistan, he receives a phone call from the American consulate in Tokyo informing him that his father has been arrested trying to infiltrate the Janjira Quarantine Zone. So much for Ford’s relaxing homecoming…

To be perfectly honest, Joe isn’t exactly sure what he thinks the Japanese government is hiding. For a long time, he figured the aim was to cover up some kind of egregious design fuck-up or construction corner-cutting, but every scrap of information he’s uncovered in his years-long search has lent itself to much more exotic interpretation. Somewhere along the line, Joe noticed the similarity between those funny seismic pulses and the ultrasonic signals of echolocating animals like bats and dolphins. Soon thereafter, he had a friend of his in the conspiracy nut community plant sonobuoys for him in the river that runs by the plant. Eventually, those buoys started picking up pulses just like the ones Joe remembers so well from fifteen years ago. That’s why he was trying to sneak into the Quarantine Zone. The computer at the Brodys’ old house is loaded with data from before the disaster, data that would allow Joe to prove that whatever happened in 1999 is about to happen again. Ford (fresh off the plane to spring his dad from jail) is reluctant in the extreme to get sucked into what he regards as his father’s madness, but finally lets himself be persuaded to come along on another foray behind the fences.

The Brodys are quickly caught, of course, but not quickly enough to stop them from learning a few things that could be extremely embarrassing to the authorities. Like how the Quarantine Zone somehow isn’t radioactive anymore, and how a new and distinctly military-looking installation has been built amid the wreckage of the nuclear plant. Also, we can’t help noticing (even if Joe and Ford don’t yet appreciate the significance of this) that the head of the mysterious new Janjira project is none other than Ishiro Serizawa. That’s entirely understandable, since the secret Monarch and the government have teamed up to keep looks exactly like one of those pods from the Philippines, except big enough to house a hundred-foot monster in relative comfort. Evidently what hatched out of the pod in the mine swam and/or burrowed its way to Janjira, destroyed the reactor to feed on its radiation, and has been pupating in the ruins ever since. You can therefore understand why Serizawa and his colleagues have thus far stood by, letting the creature do its thing; without it to gobble up the gamma rays, the whole prefecture might be an uninhabitable wasteland now. Unfortunately, as Joe has discovered, the cocoon is about to hatch, and the imago within will be considerably less tractable than the pupa. Picture a kaiju-sized palmetto bug that produces circuit-scrambling electromagnetic pulses at will, and you’ve got the general idea.

In the aftermath, US Navy Captain Russell Hampton (Richard T. Jones, from Kiss the Girls and Event Horizon) arrives on the scene to take over from the obviously outmatched Monarch. In fact, matters are even worse than anybody realizes yet, because the other pod from the Philippines— which has spent the last fifteen years entombed at the Yucca Mountain disposal facility for radioactive waste— just hatched, too. The two creatures form a mating pair, with the female three times the size of the already colossal male, although she lacks his high speed and ability to fly. Regardless of Monarch’s performance thus far, Hampton and his immediate superior, Rear Admiral William Stentz (David Stratham, of Iceman and The Brother from Another Planet), are going to need a trained monsterologist on staff, so the captain naturally brings Serizawa and Graham back with him to Stentz’s flagship, the USS Saratoga. Rather less expectedly, Serizawa insists upon bringing the Brodys as well. Despite Serizawa’s role in the discovery and management of the Massive Unknown Terrestrial Organisms (as the military have taken to calling the two giant bug-things), they’re not really his professional specialty. Joe Brody, without realizing it, studied the MUTOs for fifteen years, from angles no one at Monarch knew enough even to consider; he’s arguably the world’s foremost expert on the creatures. Ford, for his part, is valuable because Joe was gravely injured in the male MUTO’s escape, and may not live long enough to contribute his hard-won wisdom to the monster-hunting effort. Serizawa hopes that the father had a chance to pass along some of what he learned to the son over the years.

Let’s back up a bit, though. What monster could Serizawa have been focusing his attention on if not the MUTOs? Well, that takes us back to the opening credits, and to 1954. When the USS Nautilus, the world’s first operational nuclear submarine, conducted its shakedown cruise that year, it awakened something in the depths of the Pacific. Over the ensuing decades, Monarch’s scientists determined that the Nautilus creature was a holdover from distant prehistory, the apex predator of an ecosystem unattested in the fossil record. Its species ruled the Earth at a time when the ambient radiation levels on the surface were ten times what they are today, and was adapted to take sustenance from that radiation in addition to more conventional forms of nutrition. Environmental changes forced the creatures far underground and into the deepest ocean, where they could be closer to the nourishing radioactivity of the planet’s core, and the biosphere as we know it has not seen them since— except for the one disturbed by the Nautilus, which Monarch has dubbed “Godzilla.” For ten years, Monarch and the US military tried again and again to kill Godzilla with hydrogen bombs, passing off the operations as test detonations, but with no success. His organization’s continued inability to nuke the creature to death has given Serizawa some rather unorthodox ideas about its nature. He now believes that, far more than just an animal or even a monster, Godzilla is basically Mother Nature’s secret weapon against forces that threaten to throw the biosphere out of whack. Within the framework of his Shinto spiritual perspective, it is for all practical purposes a living god.

You might ask what any of that has to do with the MUTO situation, but if Serizawa is right about Godzilla, it’s distinctly relevant. For one thing it’s hard to imagine anything more destabilizing to the already embattled natural balance than the prospect of a world overrun by titan cockroaches. And furthermore, the circumstances under which the MUTO larvae were discovered suggest that they used to parasitize creatures like Godzilla back in the day. That would make the two types of monster natural enemies, introducing a strong possibility that the seismic squawking whereby the MUTOs court each other will also draw Godzilla out of seclusion. Stentz regards that prospect with unalloyed horror, and responds with a plan to lure all three radiation-munching monsters out to sea with the physics package of a Minuteman missile. Once they’ve reached a safe distance from any human habitation, Stentz will set off the warhead, and hopefully incinerate the whole ugly lot of them. Serizawa, however, thinks that’s a stupid idea. Nuking Godzilla never worked in the 50’s, and he sees no reason to imagine that it’ll work now. Instead, the scientist recommends a hands-off approach: evacuate San Francisco (toward which all the monsters seem to be converging), and let Godzilla handle the MUTOs. That, however, would require a leap of faith that Godzilla will return to the Marianas Trench or wherever of his own accord after he wins, and Stentz isn’t at all sure such confidence is justified.

I was cheating a little before, when I called Godzilla a worthy continuation of the Japanese kaiju tradition. There isn’t one such tradition but several, so which one do I think Godzilla continues worthily? It’s a more significant question than it might seem on its face, because the film director Gareth Edwards made isn’t quite the film Warner Brothers have been selling. Watch the best and most informative of the pre-release trailers— the one with Bryan Cranston’s breathless monologue about something coming to send us back to the stone age overlain as a voiceover atop images of the destruction the monsters leave in their wake— and you’ll come away with the impression that Edwards and company were aiming for the tone, themes, and subject matter of Godzilla: King of the Monsters/Gojira, but this is actually more an update of the 1960’s Godzilla movies. The mood is more serious, to be sure, but the treatment of Godzilla himself, the balance and relationship between the monsters’ story and the humans’, and the confluence of bullshit science and half-baked mysticism at the core of the premise are all straight out of Ghidrah, the Three-Headed Monster (although Max Borenstein’s script is thankfully more coherent than that). Even the rather perplexing attitude that the human characters ultimately adopt toward Godzilla feels like 60’s kaiju eiga, as an entire species apparently decides as one to let bygones be bygones once the MUTO threat is no more. That disconnect between the movie that exists and the one that was sold accounts, I think, for some of the more sullen criticism that Godzilla has drawn. Because we were cued to expect a 50’s-style allegory on nuclear power or environmental despoliation, it’s more than understandable that some people would be irritated to receive a movie that pays no more than the hastiest lip-service to either of those things.

None of this is to say that Godzilla won’t support an allegorical reading— it just won’t support one that we’d normally expect from this kind of movie. I’m also not sure how much of the reading that it will support was actually intended by the filmmakers (in the manner of Gojira and Them!), or how much of it arose unbidden from their subconscious minds (in the manner of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and most of the shoddier 1950’s monster flicks). The reason for my uncertainty is that so many of the features that make Godzilla work as allegory could equally well be interpreted as mistakes, missteps, and misjudgements. For starters, I have yet to read a review that didn’t lament the increasingly tight focus on Ford among the human characters, and I can’t deny that he’s the least interesting of the bunch. Nor can I deny that Ford accomplishes very little in the final assessment (although he does get his moment with the MUTO eggs), or that he never makes effective use of the bomb-disposal training that becomes his official excuse for hanging around at all. Elle’s skills are similarly underutilized. As a nurse in a kaiju movie, she ought normally to be in the thick of things, perhaps with her heroic efforts to cope with a sudden influx of monster-maimed patients juxtaposed against her husband’s equally desperate struggle to defend San Francisco. Instead, though, Elle spends the decisive phase of the story shut up in a bomb shelter with the rest of the evacuees, while Ford futilely pursues a loose nuke around the city. The younger Brodys are joined in their ineffectuality by the whole United States military, too, although that’s no surprise in this genre. What is perhaps a little surprising is the mechanism of the military’s failure: Admiral Stentz’s dogged determination to keep swinging the big stick no matter how often people who know what they’re talking about tell him it isn’t going to work. And speaking of people who know what they’re talking about, Joe Brody, the self-taught MUTO expert and the most interesting figure among the cast, gets put out of action much earlier than I expect anybody will like, and Dr. Serizawa quickly has his role reduced to warning people repeatedly not to do things.

What does any of that have to do with allegory? Well, doesn’t it all sound sort of familiar? The US military interposes itself into an ancient conflict between combatants its leaders understand poorly if at all, in response to a devastating attack by one of the antagonists on American soil. The best efforts of the most dedicated common soldier fail to resolve or even to contain the battle, and ultimately make things significantly worse, partly because their commanders insist on a delusionally misguided strategy, and partly because high-tech firepower is simply the wrong tool for the job in the first place. Experts in the relevant fields are sidelined, ignored, and even treated like criminals while the authorities make bullets and bombs their first and only resort. And in the end, there’s no practical solution but to get out of the way while the old enemies duke it out— even if getting out of the way means accepting the risk of becoming collateral casualties in the fight. Oh— and along the way, the expected smashing of famous skyscrapers comes packaged with whole squadrons of airplanes falling out of the sky and exploding on impact against the crumbling concrete towers. Did Edwards and Borenstein deliberately set out to render thirteen years’ worth of military, diplomatic, and foreign-policy fiasco in the Middle East as kaiju eiga? I don’t know. But I do know that the atom bomb is yesterday’s nightmare, and that each era tends to get the monsters it needs in turn.

I also know that I enjoyed Godzilla enough to go see it twice in the theater (something I very rarely do), even before I realized what it was up to beneath the surface. We may remember this as the moment when the virtues of Marvel Studios’ superhero movies— easily the most consistently well-made and entertaining action pictures of the past five years— finally took root elsewhere in Hollywood. Godzilla is as well paced and well structured as any of those, with plenty of the breathing room that far too many directors working in the field recently have treated as a useless waste of running time. Edwards never lets an action sequence play out quite the way you expect, and he appreciates the power of a good lacuna. Take the initial tussle between Godzilla and the male MUTO in Honolulu, for example. We get this tremendous build-up with the MUTO being discovered having a rather startling snack, a tidal wave swamping the city as Godzilla approaches from the sea, and that final, amazing shot of the latter monster looming up over the former, dwarfing it into insignificance despite all its well-established immensity— and then Edwards cuts to the Brodys’ son watching the creatures’ battle on the evening news. Not only does the interruption save the full effect of an all-out kaiju smackdown for the San Francisco climax, but it also jolts us back into a real-world frame of reference, inviting us to contemplate the scale of the disruption the monsters’ awakening represents. And while I’m on the subject of scale, I’ve never seen a kaiju movie so impressively convey the sheer size and power of the monsters. Note, by the way, that the 350-foot height with which this movie official credits Godzilla is way lowballed. Calculating from shots that place him next to an object of known dimensions (such as the Golden Gate Bridge, a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier, or an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer), this incarnation of Godzilla has to be just a tad under 600 feet tall, and 1200-1300 feet long from snout to tail. King of the Monsters indeed! And with fight choreography that owes much more to Gigantis the Fire Monster than any of the subsequent “versus” movies, his ferocity, along with that of the MUTOs, is nothing short of majestic. The monsters oddly come across as the most well-rounded characters, too, in a way I haven’t seen since the original King Kong. Godzilla conveys a world-weariness in keeping with his revised status as the biosphere’s night watchman, and MUTOs’ courtship, with the male feeding stolen nuclear warheads to his mate, is curiously touching, like something out of a David Attenborough wildlife documentary. I’d been avoiding Monsters, Edwards’s previous foray into this general territory, due to complaints I’d heard that it was an alien invasion movie that neglected to bring the aliens (*brrr!*— Stalker flashback…), but now it’s got a prominent place on my “to see” list.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact