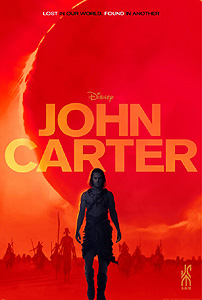

John Carter (2012) ***½

John Carter (2012) ***½

Mars is real. That’s been a conundrum for writers of science fiction and fantasy ever since astronomers began to get serious about developing better means of studying the heavens than squinting at them through pairs of little glass lenses. So long as nobody really knew what they’d see from the surface of the Red Planet, Mars offered vast scope for speculation, and what clues to conditions there could be discerned using old-school astronomical techniques certainly were enticing. Mars changes appearance over the course of its orbital cycle, as its axial tilt adjusts the relative angle and intensity of the sunlight striking it. Could those variations in color and topographical distinctness be caused by seasonal changes in vegetation? And what about those uncannily straight “channels” that Giovanni Schiaparelli thought he saw crisscrossing all over the Martian tropics? Mars has polar ice caps, and polar ice caps mean water. Could Schiaparelli’s channels be riverbeds? Or better yet, might they be artificial waterways— not merely channels, but canals? After all, how often does Mother Nature succeed in drawing a straight line? With such mysteries to ponder so close at hand, cosmically speaking, it’s no wonder that Mars would fire the imaginations of authors at every level of intellectual rigor, from Edgar Rice Burroughs to Ray Bradbury to H. G. Wells.

Then the technological bounty of the industrial revolution started to impact the science of stargazing, and the ensuing revelations about Mars specifically managed to be at once breathtaking and kind of a letdown. First, photography enabled far more detailed and objective examination of celestial bodies than was possible with telescopes alone. The heightened scrutiny proved Schiaparelli’s tropical channels to be nothing more than an optical illusion, for they stubbornly refused to show up on film, whatever other awe-inspiring topography presented itself. Then spectrographic analysis made it possible to know the chemical composition of the planet and its atmosphere, with similarly mixed results. The confirmation that Mars did indeed have air of some kind was encouraging, but the details regarding how much air and what was in it were less so. Finally, in the late 1960’s, NASA and its Soviet counterpart began to achieve basic competency in interplanetary rocketry, leading to a barrage of new findings that were even more conducive to manic-depressive reaction. On the one hand, the images beamed back Earthward from the Mariner, Viking, and Mars series of unmanned probes revealed a world apparently shaped by the action of powerful rivers and torrential rainfall, much like our own in that respect if no other. But they were also unmistakable in showing that any such torrents and cataracts had occurred eons ago, while other instruments carried by the probes demonstrated that their like would not be seen again anytime soon. The present-day Martian atmosphere was too thin and cold for liquid water to survive for long; large amounts would freeze solid like the polar caps, while mere trickles would quickly vaporize under the feeble atmospheric pressure. In between the poles was one vast, uninterrupted desert, and the planet’s oft-observed seasonal variations were caused not by plants gaining and shedding their foliage, but by tremendous, globe-spanning dust storms. Mars, in other words, was a dead planet, albeit one that tantalized with hints that it could perhaps have been capable of supporting life untold millions of years in the past.

By the time the last pieces of that disheartening puzzle were in place, however, Mars was already a tradition in fantastic fiction. The prospect of a potentially habitable world that was really there, right next door, within reach of ordinary, chemically-fueled rockets on a schedule merely inconvenient to human travelers, had been rightly irresistible, and no made-up alien planet circling some lightyears-distant sun could achieve that kind of cachet. Indeed, to this day, science fiction has never really found an adequate replacement for Mars as previous generations knew it (or more to the point, didn’t know it). Just how badly sci-fi needed the old Mars may be surmised from the fact that it persists as a setting for stories at the squishy end of the hardness scale for speculative fiction even today. Other equally obsolete venues for tales of the unknown— Darkest Africa, the Antarctic, the Pacific islands, Venus, the Moon— have fallen by the wayside except in the occasional period piece, but not Mars. In the field of cinema alone, the past decade produced Mission to Mars, Red Planet, Ghosts of Mars, Doom, and a host of minor films. And now, in defiance of all plausibly calculated odds, comes John Carter. Edgar Rice Burroughs’s A Princess of Mars was among the earliest well-known (or formerly well-known, anyway) flights of Martian-centric fancy, having first been published serially in All-Story Magazine in 1912. It was successful enough to provoke ten sequels over the ensuing 30 years, more than any other Burroughs novel save Tarzan of the Apes. And yet a full century elapsed before its hero, John Carter, made it onto theater screens despite several false starts along the way. (A low-budget Princess of Mars adaptation was rushed into video release in 2009 by the preemptive rip-off artists at the Asylum, but even then we’d be talking about 97 years’ lag-time between print and film versions. Surely that has to be some sort of record!) If ever there were a Mars story too unrealistic for the 21st century, you’d think the John Carter saga had to be it, with its several parallel lineages of intelligent humanoids and quasi-humanoids, its alien technologies based on imaginary frequencies of electromagnetic radiation, and its space travel via astral projection. Yet here John Carter is in 2012, thumbing its nose at the widely publicized findings of four decades’ worth of robotic exploration, with no more justification or apology than an opening-scene voiceover that begins, “You think you know Mars…” Indeed we do, but obviously we still occasionally need it to be something other than what we know.

What that means in this case is not a dead world, but a dying one. John Carter’s Mars— or as the natives call it, Barsoom— has for centuries been wracked by warfare among its many city-states, and the most aggressive of the lot is the mobile city of Zodanga, ruled by the brutal Sab Than (Dominic West, from Centurion and The Awakening). As you might imagine, the energy and material demands of a city that scuttles about the globe like a 5 billion-ton centipede are immense, and the Zodangans literally can’t afford not to control all that remains of their planet’s dwindling natural resources. Obviously the inhabitants of the other Martian city-states have their own strongly-held opinions on that, but the only one powerful enough to oppose Zodanga is Helium, the domain of Tardos Mors (Ciarán Hinds, of The Woman in Black and Excalibur). Or at any rate, Helium was strong enough to oppose Zodanga until Sab Than was befriended by a mysterious, shape-changing being who called himself Matai Shang (Mark Strong, from Superstition and Babylon A.D.). Matai Shang and his people took an interest in the Zodanga-Helium war for some closely guarded reason, and the shapeshifter presented Sab Than with a weapon more powerful than anything known to Martian science. The geopolitical situation on Mars has been very different since that happened.

Injecting John Carter (Taylor Kitsch, from The Covenant and Snakes on a Plane)— formerly Captain John Carter of the Confederate States Army— into that situation is a convoluted process requiring two genre detours. First comes a foray into locked-room mystery, with Carter’s nephew, Edgar Rice Burroughs (Daryl Sabara, of Machete and Rob Zombie’s Halloween), arriving at Uncle John’s Virginia mansion in response to an urgent telegram, to find Carter dead of a sudden, baffling illness. There’s a will eccentric enough for any 1920’s spooky house thriller and a secret journal containing the series of flashbacks that accounts for the bulk of the film. Then John Carter briefly turns into a Western, in which Carter squares off against a US Army colonel (Bryan Cranston, from Dead Space and Terror Tract) determined to pressgang him into signing on as a federal marshal. The Western digression also involves a legendary cursed cave containing a rich vein of gold, and a shootout with a gang of Indian bandits. The Indians end up chasing Carter and a badly wounded Colonel Powell into the cave, and that’s where Carter encounters a bald guy in flowing, black robes who looks more than a little like Matai Shang. That meeting goes badly, the alien proves not to be immune to bullets, and Carter gets zapped to Mars accidentally by the teleporter medallion the dying alien was trying to use to get himself home.

Even then, Carter doesn’t immediately find himself in the midst of the Zodanga-Helium war. No, first he falls in with a race of Martian savages called the Tharks. In sharp contrast to the manipulative shape-changers and the reddish-skinned people of the city-states, both of whom are humanoid in the strictest possible sense, the Tharks are only very roughly so. Standing anywhere from seven to ten feet tall, they are extremely slender for their size— which is only to be expected given their world’s relatively weak gravity. They also have four arms, green skin, and big, upward-pointing tusks to either side of their mouths. They exhibit no secondary sex characteristics beyond that females tend to be a little shorter and more gracile than the males, and don’t show quite the same degree of tusk development. And Tharks lay eggs, which is how Carter comes to meet them; he happens to be on the premises when the Tharks’ chief, Tars Tarkas (Willem Dafoe, from Streets of Fire and Antichrist), leads a band of warriors out to the tribal hatchery to collect this year’s brood of larvae. It’s lucky for Carter that Tharks respect physical prowess above all other things, because the same low gravity that makes the aliens’ towering, spindly bodies workable imparts prodigious strength to his Earth-bred muscles. Tars Tarkas is so impressed with his superhuman (and super-Martian, for that matter) leaping, hurling, and punching ability that he eventually goes so far as to make Carter his second-in-command— greatly to the disgust of his longtime rival for the chieftainship, Tal Hajus (Thomas Hayden Church). Carter also befriends a rebellious female named Sola (Minority Report’s Samantha Morton), and earns thereby the enmity of her rival, Sarkoja (Polly Walker, of Sliver and Clash of the Titans). Oh— and he acquires a pet, too, in the form of a huge, slobbering cat-dog-maggot monster called Woola, whose eight stumpy legs can carry it at seemingly impossible speeds.

Anyway, Carter is hanging out with that ugly lot when he witnesses an aerial battle between Zodangan and Heliumite warships. Sab Than had offered to put a stop to the war in exchange for marriage to Helium’s scientist princess, Dejah Thoris (Lynn Collins, from Bug and The Number 23); Tardos Mors was loath to push his daughter into an arranged marriage to anyone, let alone an asshole like Sab Than, but saw little choice in the matter considering the recent course of the conflict. Dejah Thoris would not submit, however, and the clash above the Tharks’ settlement is all about Sab Than trying to round up his unwilling bride. The Tharks as a whole don’t give a shit what civilized Martians do, but when Carter catches sight of Dejah Thoris while observing her besieged airship through binoculars, it sort of goes to his head. No Virginia gentleman is going to let a lady be threatened while he’s around to do something about it, damn it! Soon Carter is leaping aboard the stricken vessel to carry the princess to safety and take up arms on her behalf— so imagine his surprise when she turns out to be at least his equal at swordsmanship, even if she lacks the advantages conferred by growing up on a higher-gravity planet. He’ll resist at first the call to do more than to help fend off this particular attack (the death of his wife and child as collateral casualties of the Civil War has soured him on his former profession), but that intervention inevitably ends up being Carter’s first step toward becoming the liberating hero of Barsoom.

John Carter is to some extent the victim of its source material’s success. The Barsoom novels (of which this movie is a composite adaptation of the first three) have been among the most influential works of their kind in the English language, and much of the film is likely to seem familiar to people who have, for example, seen Avatar, or watched Filmation’s “Blackstar” and “He-Man and the Masters of the Universe” cartoons, or read Richard Corben’s Den comics— not because John Carter is copying them, but because they were copying its literary basis. It’s a risk filmmakers run anytime they adapt a very early example of a long-established genre. But while it’s true that John Carter is likely to disappoint those who come to it seeking something they haven’t seen before, it delivers impressively in terms of things I haven’t seen in a long time. Anybody who misses the unabashed whimsy of pulp-era sci-fi, or the confident grandeur of the pre-1970’s Hollywood epics (which is to say, among other things, the ability to tell a big, wide-ranging story without dragging it out into a three-hour running time or worse yet, a trilogy), or elaborate action scenes shot in such a way that their scale and complexity can be fully appreciated will find much to enjoy here. So, for that matter, will anyone who’s been pining for a carefully crafted adventure film, as opposed to yet another mere Big, Dumb Action Movie.

The grandeur and whimsy we can probably attribute to Disney being the ones who finally got A Princess of Mars, The Gods of Mars, and The Warlord of Mars (more or less) into theaters. My longstanding antipathy for that studio is hardly a secret at this point, but I can’t fault Disney’s willingness to commit big-time resources to the occasional quirky project in between all the cynical direct-to-kid-vid sequels to antique “princess” cartoons that probably pay most of the bills at the House of Mouse these days. Disney’s involvement also meant that of the computer animation wizards from their sister-studio, Pixar (indeed, John Carter was originally announced as a Pixar production), which all but guaranteed that this movie would be every bit as immersive and very nearly as wondrous as the versions that have been playing in Burroughs fans’ heads since 1912. The Pixar team’s Tharks could have stepped right out of Michael Whelan’s late-70’s paperback cover illustrations, yet are so supple and naturalistic that the performances of their voice actor/motion-capture models come through them as if they were mere costumes. The digitally-created streets and skylines of Helium and Zodanga generally seem as tangible as the sets for the more modest interiors (the principal exception being the latter city’s legs, which have a pronounced video game look), and of equal but less obvious importance, the rival city-states each have their own distinct architectural and aesthetic personalities. The airships are in some ways the coolest things of all, resembling an eccentric cross between Hellenistic-Age fighting galleys and World War II heavy bombers. The one part of John Carter’s Mars that disappoints is the landscape itself, which bears far too pedestrian a resemblance to the Arizona of the Wild West flashback sequence. A lighter touch with the digital color correction in the Earthbound parts of the film might have been enough to eliminate that problem.

All that was to be expected, of course. The big surprise is how un-Disney-like— and for that matter, un-Pixar-like— the whole thing feels. There are some echoes of the traditional Pixar style, to be sure. Most particularly, Woola as rendered here would need just a few tweaks of cartoony stylization to fit comfortably into Monsters Inc., and John Carter displays much the same sense of humor as Finding Nemo and WALL-E, both of which were also written and directed by Andrew Stanton. In the latter department, the persistent inability of the Tharks to grasp that “Virginia” is not Carter’s name, but the name of his homeland, strikes me as an especially Stantonian touch. On the whole, though, John Carter is a basically serious pulp fantasy tale, aimed less at the young than at the young at heart. I would call it a worthy successor to the likes of The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and Jason and the Argonauts, except that it’s actually quite a bit better than any of those movies. Disney has come a long way, in other words, from its last sustained attempt at courting a broader audience. John Carter might not make the studio any more money than did Tron or The Black Hole, but I fully expect that in years to come, it will be fondly remembered even by people who weren’t seven years old when they saw it for the first time.

The main reason why is that John Carter (unlike the works of the original Dark Disney in the late 70’s and early 80’s) has more to offer than a compelling aesthetic sensibility and a few half-baked good ideas. Taylor Kitsch makes for a suitably charismatic action hero, to start with, although his tendency toward scowly, Batman-ish brooding is rather at odds with the movie’s overall tone. Dominic West does similarly well as a smug and smarmy bastard; his Sab Than is believable both as someone who would get it into his head to conquer the world, and as someone who’s maybe just a little too simpleminded to pull it off without the aid of an ally like Matai Shang. Willem Dafoe reveals an unexpected knack for comedy in a generally non-comic role, a bit like John Rhys-Davies as Gimli in the Lord of the Rings series. Stanton blazes through most of the two-hour-plus running time to give the impression of a significantly shorter film— with the caveat that less patient viewers are likely to be somewhat frustrated with how long he takes to get Carter to Mars in the first place. But most of all, John Carter distinguishes itself with an uncommonly canny understanding of what material from the source novels would and would not fly a hundred years after they were written. The plot elements drawn from the first three Barsoom books are woven together here much more effectively than Burroughs managed, and considerable dead weight has been discarded. Although the practiced eye will spot where certain concepts and developments have been held in reserve for a sequel, John Carter nonetheless has an easier time standing on its own than any of its print antecedents. (A Princess of Mars, The Gods of Mars, and The Warlord of Mars each seem fragmentary on their own, amounting to a satisfying whole only when read in rapid succession.) Stanton even finds a worthwhile use for the conceit that Burroughs was John Carter’s nephew, which in A Princess of Mars and its successors was nothing but a nod toward the convention of passing off tales of the fantastic as “true” stories gleaned from lost diaries, ancient manuscripts, and the like— a convention that was antiquated in 1912, to say nothing of its utter obsolescence today.

The biggest and most astute improvement, though, concerns the movie’s handling of Dejah Thoris. To be sure, Edgar Rice Burroughs always did better by his heroines than was typical in pulp fiction of his day. By the standards of the 1910’s, his Dejah Thoris is gritty and resourceful, and much more credibly appealing on that score than any mere damsel in distress. Even so, the 21st-century reader notices at once that her primary function is still always to be rescued from some sort of peril, for her laudable efforts to escape or to overcome on her own somehow never quite reach fruition. Andrew Stanton’s Dejah Thoris doesn’t have that problem. Indeed, she might be seen as the fulfillment of the original’s promise. The movie plays up her status as one of Barsoom’s foremost scientists by introducing the princess on the verge of discovering the very same electromagnetic phenomenon that underlies Matai Shang’s death ray. It makes her a fighter of great skill and courage, and drops altogether the stuffy concern for custom and propriety which figures rather too strongly in her personality as presented in the novels. When John Carter hauls out the old “save the heroine from having to marry the villain by busting in on them in mid-ceremony” routine, it earns the cliché by having Dejah Thoris agree to the wedding, if not exactly of her own free will, then at least with a stateswomanlike recognition of what she may gain for her people as a consequence. In short, the film updates Dejah Thoris to preserve, in a modern context, what was always the most radical aspect of Burroughs’s fiction, his notion that a woman becomes worthy of a hero’s affection not by being beautiful or virtuous or well-bred, but by being heroic herself. It’s a shame that John Carter looks poised to become a fiscal disappointment, because I would very much like to see what this team could do with the rest of the saga.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact