Halloween (2007) **

Halloween (2007) **

I’m not sure what, exactly, but I feel like it says something about how the 21st century has gone so far that the person who came closest to permanently killing off Michael Myers was not Laurie Strode or Dr. Loomis or Jamie Lloyd or even Freddie Harris, the kung-fu-fighting internet reality show entrepreneur, but rather the al-Qaeda in Iraq suicide bomber who blew himself up in the lobby of the Grand Hyatt Hotel in the Jordanian capital city of Amman on November 9th, 2005. Moustapha Akkad, longtime master of the Halloween franchise, was in that lobby at the time, together with his daughter, Rima; neither one survived for long after the bomb went off. Ironically, what brought the Akkads to Amman in the first place was a project which Moustapha had hoped would go some way toward counteracting the rising dominance of men like their killer as the face of Islam in Western eyes. The elder Akkad, who got his start as a filmmaker with The Message, a pious epic in approximately the Cecil B. DeMille mode about the life and prophetic career of Muhammad, was planning to return to his roots with a biopic of Saladin, the Kurdish warrior-king whose credentials as a man of honor, faith, and culture were so impeccable that they were recognized even by his adversaries in the Third Crusade. The producer’s untimely death put a stop not only to that film, but also to several competing visions for a notional Halloween 9. (One of those, incidentally, was even crazier than the various unused premises for Halloween 6. Although Akkad himself was opposed to the idea, which furthermore fared very badly in an online fan poll, the leadership at Dimension Films wanted to counter New Line Cinema’s Freddy vs. Jason by pitting Michael Myers against the Cenobites of Hellraiser! They even got as far as soliciting story input from Clive Barker!)

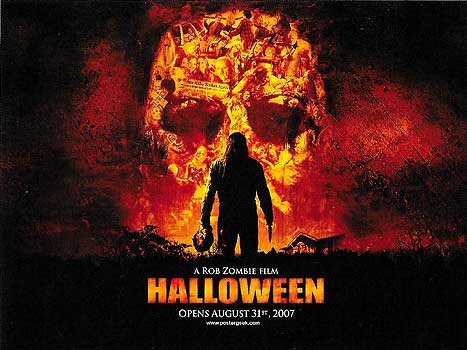

Still, a cash cow is a cash cow, and those rarely go unmilked for long in Hollywood. Malek Akkad took a little while to get his feet under him after assuming control of the family business, but once he did, it was only a matter of time before he started thinking about what Michael Myers could do for him. By then, though, it was obvious that there was a whole new fashion in derivative genre filmmaking: endlessly reiterative sequels were out; gritty-slick remakes were in. The younger Akkad broke with his father’s habits by falling immediately into agreement with the Dimension bosses, not only as to the need for a shift in direction for the Halloween franchise, but also regarding who should be the one to give Halloween its fresh start. Rob Zombie, then riding high on the success of his unaccountably beloved The Devil’s Rejects, was both parties’ top choice to put a new Halloween into the arena alongside The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Dawn of the Dead, and The Hills Have Eyes. But perhaps inevitably, Zombie’s take on Halloween proved considerably more divisive than either of his prior films. It performed well enough to earn a sequel two years later, but provoked much wailing and gnashing of teeth from both John Carpenter loyalists and Gen-X grindhouse diehards. For my part, I’m as conflicted personally as the Halloween fanbase was in aggregate. Rob Zombie’s Halloween starts off as a top-notch killer kid movie, but grows increasingly unsatisfying once its version of Myers grows to adulthood, and the remaking of Carpenter’s Halloween begins in earnest.

Ten-year-old Michael Myers (Daeg Faerch, from Dark Mirror and Ditch Party) leads a pretty shitty existence for a boy his age. An underachieving student and a chronic discipline problem, he’s not much liked by the teachers and faculty at Haddonfield Elementary School. Tubby, shy, and strange-looking, he’s also a magnet for the malign attention of bullies, and repellant to his peers in general. His parents are divorced, and his stepfather, Ronnie White (William Forsythe, of Larva and Relentless 3), has always hated him at least as much as the kids at school. His teenaged sister, Judith (Hanna Hall, from Visible Scars and Text), considers him nothing better than a nuisance, and has as little to do with him as possible. (To be fair, Judith has her hands full keeping Ronnie’s off of her, and boys Michael’s age really are the absolute fucking worst.) The Myers family was teetering on the brink of poverty even before injuries to Ronnie’s neck, leg, and hand took him out of the workforce, and although Michael’s mother, Deborah (Sheri Moon Zombie, from The Lords of Salem and Toolbox Murders), earns almost as much from her new job stripping at the Rabbit in Red Lounge, the money comes at a high cost in social standing for a family that never had much of it to begin with. Also, strippers work at night, so Michael doesn’t see much of his mom these days. About the one bright spot in the boy’s life is his baby half-sister, Boo, toward whom he exhibits the fierce protectiveness of one who knows well how much sheer imbecile cruelty the world holds in store for the weak and helpless.

The thing is, all that misery has made Michael cruel, too. With the twin exceptions of Boo and his mom, he hates his fellow humans with a passion that eclipses even their loathing for him. For that matter, Michael despises himself as well, evidently agreeing with his various persecutors’ assessments of his character and value. And so Michael indulges in the favorite self-medication technique of budding young psychos everywhere: he tortures and kills animals. He’s surprisingly shrewd about it, too, presenting himself to everyone else as a devoted keeper of rats, hamsters, and the like— short-lived, easily ignored creatures whose sudden, unexplained deaths will not be looked at askance even by his frequently absent mother. Meanwhile, Michael seeks a second form of solace in the wearing, collection, and making of masks. It makes sense, given his troubled relationship with his own identity.

Of course, we all know this kid is going to trade up from rats to people eventually, and the impetus comes one afternoon when a bully named Wesley (Daryl Sabara, of John Carter and The Green Inferno) taunts him in the boys’ bathroom with a flyer from the Rabbit in Red prominently featuring Deborah’s likeness. Michael lashes out in defense of his mother’s honor, but all that gets him is a bloody nose and a meeting with the principal (Richard Lynch, from Vampire and The Sword and the Sorcerer), who inevitably blames him for the altercation. After school, Michael dons one of his masks— it’s Halloween, so no one who sees him will think twice about that, even if there are still several hours until sundown— and lies in wait for Wesley along his usual route home through the woods. Between the sneak attack and the honking big stick Michael wields as a club, Wesley doesn’t fare nearly as well as he had in the bathroom earlier, and although I honestly don’t think Michael set out with this result consciously in mind, seeing one of his countless enemies reduced to a bleeding, pleading mess on the forest floor gives Myers that final, fatal nudge into pummeling the prostrate bully until he stops moving. Wesley’s will be only the first of four murders that Michael commits before the sun rises on All Saints’ Day, too. That night, after Deborah goes to work, the boy masks up a second time, and takes the biggest knife in the kitchen first to Ronnie, then to Judith’s lout boyfriend (Hatchet’s Adam Weisman), and finally to Judith herself. Deborah returns home to find her gore-soaked son dandling Baby Boo on the front porch of a house strewn with mangled corpses.

Michael winds up at Smith’s Grove Sanitarium, under the care of psychiatrist Samuel Loomis (Malcolm McDowell, from Class of 1999 and Doomsday). Over the ensuing fifteen years, the Myers boy becomes both the greatest failure of the doctor’s career and his greatest success. On the one hand, the state of Michael’s mental health goes nowhere but straight downhill. He withdraws ever deeper into himself, becoming ever more silent, ever more passive, ever more unreachable. He makes paper mache masks with all the dilligence of obsession, and becomes increasingly insistent about never being seen without one on his face. Eventually, the day comes when he will no longer speak to anyone at all, for any reason— not to Dr. Loomis; not to Ismael Cruz (Danny Trejo, of The Hidden and Nightstalker), the gruff but kindly orderly who was the closest thing to a friend that Michael had at the sanitarium; not even to his own mother. Deborah finally shoots herself once she grasps that the boy she so loved despite his terrible crimes no longer exists for all practical purposes. The shape of Loomis’s failure should be self-evident by now, but as for his success… well, he does write a book. With Michael grown into a terrifying, expressionless giant (Tyler Mane, from The Devil’s Rejects and Penance Lane), Loomis becomes a famous man on the strength of The Devil’s Eyes, his case study of Myers’s background, crimes, and confinement at Smith’s Grove. By that point, the sanitarium director (Udo Kier, from Trauma and The Story of O) and head psychiatrist, Dr. Koplenson (Clint Howard, of Silent Night, Deadly Night 4: Initiation and House of the Dead), have long given up their most infamous patient as untreatable, and even Loomis is finally forced to agree.

There might matters have stood for the rest of Michael’s life, had Smith’s Grove not hired a slimy redneck named Noel Kluggs (Lew Temple, from Becoming and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning) as an orderly. Kluggs is dumb and mean, just like Ronnie White, and he treats the inmates under his care pretty much the same way Wesley treated the other kids at Haddonfield Elementary. He also seems to get a special thrill out of holding power over a notorious multiple murderer, however little Myers might rise to the bait that Kluggs regularly tosses out. One night, when Kluggs is working the graveyard shift and has Michael’s ward essentially all to himself, he lets a friend of his known by the improbable nickname of Z-Man (Bill Moseley, of The Convent and House of 1000 Corpses) come up to have a little fun with a newly committed patient (Olga Hrustic, from Millennium Crisis and Bikini Bloodbath)— or at any rate, that’s what happens in the director’s cut. I’ve read that the theatrical version handles this part of the story differently, but no source that I’ve consulted specifies how. Be that as it may, Kluggs has the catastrophically bad judgment to use Michael’s cell as the venue for the rape, giving Myers both a provocation to act and an opportunity to escape from the asylum in a near-total massacre of the Smith’s Grove overnight staff. Not even Ismael Cruz escapes the slaughter. Koplenson and the director naturally don’t work nights, however, and neither does Dr. Loomis. No sooner do the former get the news that Myers has flown the coop than they call in the latter to clean up the mess for them.

Loomis is pretty sure he knows where Myers will go, and he thinks he has at least some idea what he’ll try to do when he gets there. The doctor’s theory is that the killer is bound for his childhood home in Haddonfield to seek out Baby Boo, the last remaining member of his family— although it’s harder to guess what Michael might do if he finds her. Anything up to and including killing both the girl and himself seems plausibly in the offing. The race between Loomis and Myers will be complicated, however, by the fact that only one man alive knows for certain what happened to Boo after her mother’s suicide. Haddonfield’s top lawman, Sheriff Lee Brackett (Brad Dourif, from Urban Legend and The Eyes of Laura Mars), was just a beat cop in those days, and he happened to be the first on the scene when neighbors reported gunshots at the Myers residence. Brackett figured it would be terribly unfair to the infant for her family’s lurid tragedy to follow her throughout her life. He therefore dropped Boo off at the nearest orphanage as a foundling, leaving the Myers baby’s “disappearance” to become just one more of the case’s insoluble mysteries. That knowledge will make Brackett a doubly valuable ally for Loomis, but first the shrink will have to convince the sheriff to trust him. After all, that book of his left a bad taste in a lot of people’s mouths here in Haddonfield.

But to return to the Myers baby, she was adopted locally, by real estate agent Mason Strode (Pat Skipper, from Ed Gein and Hellraiser: Bloodline) and his wife, Cynthia (Dee Wallace, of Popcorn and The Plague). She goes by Laurie Strode now, and her adoptive parents haven’t the slightest inkling of her true origin. Laurie (Scout Taylor-Compton, from Wicked Little Things and Ghost House) is one of Haddonfield’s most in-demand babysitters, and on Halloween morning— the fifteenth anniversary of her original family’s virtual extermination— she’s walking one of her favorite charges, a kid by the name of Tommy Doyle (Skyler Giscondo), to school. On the way, she and Tommy swing by the old Myers house, which her father has finally managed to sell, to drop off some things that the new owners are going to need when they take possession of the place in a few days. Alas, Michael got there first, and some uncanny faculty enables him to recognize the teenager who briefly comes to the front door as the infant whom he returned to Haddonfield to find. Retrieving both the knife he used for his long-ago family massacre and an eerily blank rubber Halloween mask from their hiding place under the floorboards, Michael spends the rest of October 31st tracking Laurie’s movements around town— and killing her friends, Lynda (Kristina Klebe, from Zone of the Dead and Proxy), Bob (Nick Mennell, of Friday the 13th and My Little Eye), Annie (Danielle Harris, who gave previous incarnations of Michael Myers a very hard time in Halloween 4 and Halloween 5), and Paul (Max Van Ville), as they cross his path in turn.

Ever since I reviewed the original Halloween, I’ve been harping on the inexplicability of Michael Myers as the engine of his effectiveness as an agent of horror. And ever since I reviewed Halloween II, I’ve been grousing about the sequels’ various attempts to explain him as doomed exercises in self-sabotage. Consequently, it always made perfect sense to me that most of this Halloween’s detractors singled out Rob Zombie’s decision to give the character a full-on origin story as its critical flaw, and I’ve been sympathetic to the related critique that it doubly diminishes Myers to make him the spawn of the vilest imaginable “Jerry Springer” guests. After all, what Zombie has done here is to turn the most frighteningly inscrutable of slasher killers into the most relatable: if this were your family, you’d want to hack them into little bitty pieces, too! So imagine my astonishment as I watched Halloween, and realized that the origin section— the part that, sight unseen, I’d have told you should obviously never have existed— was not merely the best part of the film, but was downright done dirty by the need to channel it into a Halloween remake that nobody outside of the Akkad family or Dimension Films had asked for.

Most slasher movies that provide a concrete origin for their killers essentially subscribe to the One Bad Day theory of madness put forward by the Joker in Batman: The Killing Joke. The murderer-to-be was getting along just fine, more or less, until some discrete catastrophe turned their life upside down, and left them with an irresistible drive to carve up the perpetrators, people like the perpetrators, or maybe even anybody at all who crosses them for the rest of their lives. While I won’t deny that it probably does happen that way on occasion, the alternative theory that Rob Zombie offers in Halloween strikes me as much more credible: the problem isn’t that Michael Myers had One Bad Day, but rather that he’s never had a good one. Whatever capacity Michael might ever have had to function as a whole human being has been steadily ground out of him by inhumane treatment, and the one person who genuinely tried to do better by him before it was too late simply never had enough time or attention left over from the struggle to earn a living. Subsequent interventions from well-intentioned outsiders like Dr. Loomis and Ismael Cruz had the opposite of the desired effect, driving the boy deeper into pathology until there was no longer any way out. Cruz’s efforts to befriend Michael are especially interesting in that regard, given Danny Trejo’s own background. If we assume something even vaguely similar for Cruz, it becomes both obviously natural that the orderly would see in Michael somebody who deserves a chance for redemption, however far fetched, and readily understandable that Myers would internalize Cruz’s advice in the most destructive possible way. And having given the killer not merely an origin, but a psychologically astute one, Zombie takes the final extra step of giving him also a sufficiently convincing reason to break out of the asylum when and how he does. What reactivates Michael’s murderous impulses is the same thing that awakened them in the first place, an act of sadistic bullying against a victim too weak to fight back. It’s just that this time, the victim in question isn’t him. So while it’s true that Zombie has done exactly the thing I’m always complaining about with respect to Halloween movies specifically, he did so by following exactly the admonition that I’m forever leveling at the perpetrators of remakes in general. He’s given us an interpretation of Halloween that covers acres of new ground in a thoughtful, intelligent, and mostly effective manner. It’s only when his Halloween returns to the original’s well-trod turf that it falls apart.

The most vital element of Halloween’s successful first half is Daeg Faerch as the young Michael Myers. To begin at the most superficial level, the lad really does look like somebody whom other kids would instinctively dislike, with his odd bodily proportions, malingering baby fat, stringy hair, and wide-set, lusterless eyes. For that matter, he also has the appearance of someone who might be small for his age now, but is apt to become truly immense once he hits his adolescent growth spurt— a desirable quality indeed in a child whose adult form is to be played by Tyler Mane! But what makes Faerch really special in the part is his ability to convey the volatile mix of despair and desperation that characterizes a child who knows that he’s truly alone against the world. He makes Michael’s self-loathing as poignant as his butchery of pets is disturbing, and throughout Faerch’s entire performance shines Michael’s white-hot love for a baby sister who, unlike him, hasn’t yet fallen victim to the squalor surrounding them both. I haven’t seen a lone juvenile actor so dominate a film since Natalie Portman tucked The Professional into her purse and walked off with it— and Faerch is only in half of Halloween!

Truth be told, though, even the weak second phase isn’t quite as hollowheaded as it seems on the surface, although everything preventing it from being so is deeply rooted in the first. It’s a matter of motivation, both Michael’s and Dr. Loomis’s. The sensational title of his case study on Myers notwithstanding, this incarnation of Loomis is not at all the Van Helsing-like monster hunter we’ve been trained to expect by the original Halloween and its numerous sequels. Far from considering Myers “purely and simply evil,” Rob Zombie’s Loomis is driven even after Michael’s escape by a doctor’s concern for his patient, and by the recognition that none of this would now be happening if he had been able to reach Myers at any point during the preceding fifteen years*. And on Michael’s end, it becomes increasingly apparent as the film wears on that his intentions toward Laurie are what passes for benign in his twisted mind, and that he turns against her only because she rejects his bid to install himself as her captor-cum-guardian. That might be the best imaginable use for John Carpenter’s calamitous early-80’s retcon of the relationship between the two characters, and its revelation makes shockingly good sense of Michael’s consistent failure to strike his supposed primary target in any serious way. And because the back half of Halloween otherwise seems like such a witless recitation of genre clichés whenever Loomis isn’t around, it’s jarring in the best way when we learn at last what Michael is really up to.

It might seem strange to you that I’ve spent most of this rather long review praising a movie that I consider to be just barely adequate on the whole. It certainly seems strange to me! But the most damning characteristic of Rob Zombie’s Halloween is that its increasingly dominant bad parts aren’t even bad in an interesting way. The heap of junk into which Halloween collapses in the second half recalls insignificant crap like Bloody Moon or The Mutilator much more than its actual source material, so that it becomes difficult to find any specific, individual condemnation to level against it. It’s just another crummy slasher movie, with every drearily familiar old defect that usually implies. The same goes for each of the various 30-something “teenagers” on the sharp end of Michael’s knife this time out, too. Michael’s victims simply make no impression whatsoever, for good or for ill, in life or in death. Even Scout Taylor-Compton (who alone among this bunch had any business attempting to play a high-schooler in 2007) as Laurie is an absolute nonentity, a negligible rendition of a role dictated solely by the fossilized expectations of a fanbase disinclined to bother asking for anything better. That, I believe, is the surest measure of the futility of remaking Halloween in the 21st century. There’s so little meat left on the carcass by this point that barely any options beyond rote repetition present themselves once Myers is out of the sanitarium and on the rampage.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact