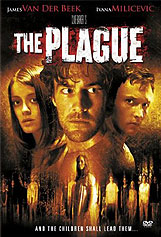

The Plague (2006) **˝

The Plague (2006) **˝

It isn’t often anymore that I encounter a variation on the zombie-movie theme that I haven’t seen before. Partly that’s because I’ve watched so many zombie movies, but it’s also because the people who were most interested in making the things up until comparatively recently— which is to say, direct-to-video fly-by-nighters— have for the most part been perfectly content to sprawl out and make themselves comfortable in the rut that George Romero, Lucio Fulci, Bruno Mattei, and the rest dug for them close to 30 years ago. In fact, it’s gotten to the point now where the most interesting zombie movies often don’t feature zombies, strictly construed, at all. The Plague, for example. The Plague is not a true zombie film, in the sense that there are no walking dead people in it, but in terms of premise, plot structure, and character dynamics, it might as well be. It has a mysterious disease that threatens to bring about the end of the world by turning people into things that aren’t quite human anymore, it has protagonists thrown together by circumstance who mostly don’t like each other very much, and it involves quite a lot of holing up inside hastily fortified buildings before having it demonstrated that to do so is tantamount to suicide. In the details, though, what we have here might best be thought of as Village of the Damned by way of The Crazies.

One morning, David Russell (Arne MacPherson, from Eye of the Beast and Population 436) goes to get his son, Eric, up for school, only to find him catatonic and foaming lightly at the mouth. Russell rushes the boy to the hospital, where he is astonished to find every other parent in the small town of Keenan already filling up the emergency room with catatonic kids of their own. There’s a TV in the waiting room, tuned to the morning news, and thus David learns (as do we) that the problem is nationwide if not worldwide— at approximately 5:00 that morning, every child under the age of nine everywhere lapsed into an unexplainable trance. Nor apparently is catatonia the only symptom of the curious plague, for a few minutes after David finally manages to take in what he’s seeing at the hospital, every one of the afflicted kids launches simultaneously into a mild sort of seizure, twitching their limbs and vibrating their bodies.

That was ten years ago. None of the kids who went under that day ever got better, and every baby born anywhere on Earth since then has come into the world comatose. Nobody has any idea what’s causing that, either. Governments all over the globe are gearing up for total societal collapse, as the 3.5 billion-year-old mechanism for population replacement strips its gears, and the potentially productive fraction of the human race starts shrinking from both ends instead of just one. Even cute-‘n’-cuddly democracies begin passing draconian anti-childbirth legislation to arrest the drain on the world’s resources, and bloody rioting breaks out in parts of the world where such edicts are imposed from above without public deliberation. Little Eric is now a teenager (Chad Panting), and strangely enough, he’s as strong and healthy as anyone his age who hasn’t spent the last ten years lying motionless in bed. No one ever says so explicitly, but it seems probable to me that whatever disease agent is at work here needs its hosts in good physical condition, and that the twice-daily seizures are its way of making sure the afflicted get their exercise. Anyway, that’s the situation when David’s little brother, Tom (James Van Der Beek, going to great lengths to put “Dawson’s Creek” behind him), comes back to Keenan, looking for a place to stay, at least for the short term. Sometime in the past, Tom accidentally killed a man in a bar fight, and he’s just been released on parole. He can’t go back to his own house, because his wife, Jean (Ivana Milicevic, from The Devil’s Child and the pilot movie for the USA Network’s abortive, Dean Koontz-developed “Frankenstein” series), divorced him shortly after he went to prison, and she’s in no mood to take him back. In fact, just about the only person in town who seems at all happy to see Tom is Jean’s brother, Sam Raynor (Brad Hunt), who was apparently his best friend back in the day— unless maybe you count the gleeful anticipation with which Sheriff Cal Stewart (John P. Connolly, of When the Bough Breaks) looks forward to catching Tom in a parole violation as a form of happiness. David agrees to take Tom in, but he obviously does so at least a little grudgingly.

We can safely forget about the small-town soap-opera shit, though, because all those catatonic kids awaken just as suddenly and inexplicably as they went comatose in the first place, and the only thing on their minds when they do so is slaughtering their elders. Most of the primary caretakers— David included— are killed almost immediately, unprepared as they are for anything even slightly resembling their loved ones’ attacks. Despite the gulf of acrimony between them, Tom’s first thought when chaos erupts is for Jean, who works as a nurse at the high school where those kids whose families were unable to care for them at home had been bivouacked, and he and Sam make their way there at once. Nor are they the only ones with that idea, for Sheriff Stewart and his deputy, Nathan Burgandy (Bradley Sawatzky), are also on the way over. Jean is still alive, along with several of her fellow nurses and the doctor (John Ted Wynne) in charge of caring for the formerly catatonic kids, but the dual rescue mission does few of them any good. Jean alone survives to escape the overrun school, although her rescuers also pick up two more curious hangers-on: Kip (Joshua Close, from Diary of the Dead and The Exorcism of Emily Rose) and his girlfriend, Claire (Brittany Scobie, of Something Beneath and Maneater), two teenagers just old enough to have dodged the plague bullet, who have been getting by thus far on the apparent inability of the zombies (for want of a more accurate term) to distinguish them from their own. The group also rendezvous with Stewart’s wife, Nora (Dee Wallace, from The Hills Have Eyes and Rob Zombie’s Halloween), shortly after fleeing the school.

Naturally, everybody’s first idea is to seek shelter somewhere, with the final consensus being that the village church seems like the best bet. They arrive just in time to see Jim the pastor (Gene Pyrz, in a part only slightly larger than his blink-and-you’ll-miss-them appearances in Resident Evil: Apocalypse and Trucks) getting killed by what might ordinarily have been his own church youth group, but are able to secure the building against further attack— for the most part. You see, among the mob that got Jim was Alexis Stewart (Hilary Carroll), the daughter of Nora and the sheriff, and Nora in particular can’t bear to be separated from the girl now that she’s awake. The men tie Alexis to the altar, but I imagine that everyone reading this can see already how badly that’s going to go. In fact, it’s going to go even worse than you probably think, for the zombie kids are all in some kind of telepathic communication, and what one knows, they all know. Those who remain alive after the inevitable catastrophe at the church conclude at that point that the time has come to take their leave of Keenan, and hope that authorities elsewhere with greater resources have enjoyed more success in dealing with what history will no doubt remember as the Rude Awakening. Naturally, that strategy doesn’t go too well, either.

Some DVD editions proudly bill The Plague as “Clive Barker’s The Plague.” The film is in no way derived from anything Barker wrote, and indeed his only involvement was leadership of the production company for which it was originally developed. In other words, if you became interested in this film solely because you saw his name above the title, feel free to go back to not being interested again; it’s a decent movie, on the whole, but it bears no resemblance to anything Barker might have dreamed up himself. It apparently also bears very little resemblance to the movie writer/director Hal Masonberg and his scripting partner, Teal Minton, set out to make, having been maimed in one of those distributor-on-production-company-on-filmmakers tugs of war that always wind up improving a movie ever so much, and that may go a long way toward explaining some of its less satisfactory qualities. It might, for instance, make sense of the jarring shift in tone from the quiet eeriness of the first act to the relatively pedestrian zombie-movie action of the second and third, or of the movie’s determined short-changing of every interesting bit of character development it sets up. On the other hand, the wrangling with the money men probably can’t account for The Plague’s most serious weakness, unless there was a considerable amount of re-shooting involved in addition to the re-editing. What hurts this movie the most is its ending, in which a long-running subtextual theme is explicitly transformed into a central plot point, replacing disquieting mystery with horseshit mysticism in the process. Sometimes, making a horror movie “about” something is greatly preferable to making one about it, and The Plague is one of those cases.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact