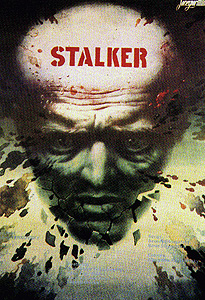

Stalker (1979/1982) *

Stalker (1979/1982) *

Because I apparently do not know when to quit, I decided to follow up my screening of Solaris/Solyaris by watching Stalker, another three-hour misery marathon from Solaris director Andrei Tarkovsky. I probably should have spent the time sticking pins in my eyes instead— I’d have gotten more out of the experience.

Again, Tarkovsky has begun with a premise that could have yielded a compelling cerebral sci-fi film, but with Stalker, he has indulged even more profligately in purposeless philosophizing, and the result is something close to completely unwatchable. For example, you might expect a three-hour movie (okay, so I guess it’s closer to two hours and 45 minutes, but that’s enough like three hours for me) to require an exceedingly long review— you can fit a damn lot of plot into that much time, after all. But as you can see, this is not the case, for the simple reason that between minute number 45 and minute number 140, there is absolutely no story to comment upon! That is to say, Tarkovsky has devoted the equivalent of an ordinary movie’s complete running time— credits and all— to directionless introspection on the parts of his characters. Any director who will so wantonly waste an hour and a half is no friend of mine, let me tell you.

The idea here is that, in the not-too-distant future, some sort of celestial object— a meteorite, an alien spacecraft, something completely unimaginable, who knows?— has landed in the countryside of what I take to be East Germany. The authorities reacted immediately, surrounding the general vicinity with a cordon of police roadblocks and barbed-wire fences before sending in the army to deal with anything living that might have arrived with the thing from space. Nobody heard word one from any of those soldiers again. However, rumors soon started circulating to the effect that, somewhere in the Zone (as the blocked-off region around the crash site has come to be called) is a place where some mysterious force grants the most heartfelt wishes of those with courage (or desperation) enough to find it. Before long, a veritable underground industry cropped up in which men and women who lived near the Zone would sell their services as guides, leading small groups past the roadblocks and barbed wire— and through the more subtle dangers of the Zone itself— to the mysterious Room, where dreams can come true. These guides are the Stalkers.

The Stalker with whom well shall concern ourselves (Aleksandr Kazhdanovsky) lives in a crumbling city just miles from the Zone with his wife (Alisa Freyndlich, from The Secret of the Iron Door) and daughter. Mrs. Stalker would rather her husband get himself a real job; not only is what he does illegal (he’s already been sent to prison a couple of times), it is well known that Stalkers don’t always come back from their expeditions, and that even those who do may eventually be undone by the strain of frequent exposure to the wonders and terrors of the Zone. Indeed, the couple’s daughter has already paid a heavy price for her father’s activities, in that she was born legless, mute, and telekinetic due to the havoc the Zone has already wreaked on the man’s chromosomes. Nevertheless, our Stalker is on his way out the door when we meet him, headed for a rendezvous with a scientist (Nikolai Grinko, whom Tarkovsky had directed before in Solaris) and a writer (Anatoli Solonitsyn, another Solaris graduate) who want to be taken into the Zone.

The first step on the journey is to get out of the city. That means evading the patrolling cops (for whom keeping people out of the Zone is a major part of the job) long enough to sneak into the rail yard which the military uses to send troops and equipment to destinations on the other side of the Zone. It’s a hectic morning for the Stalker and his two pilgrims, but they do eventually make it by all the guards and steal a railroad handcar to ride into the Zone. You might expect the police and soldiers to pursue them; after all, railroad handcars have never been high on any criminal’s list of preferred getaway vehicles, what with their very low speed and their inability to go anywhere that is not served by railroad tracks. But the border guards have a very good reason for letting the escapees go unmolested once they’ve entered the Zone— the cops and soldiers are all scared shitless of the place.

Why? That’s a good question, there. Supposedly, the Zone is a place where reality breaks down, and whatever otherworldly intelligence dwells there is at pains to deter all but a select few visitors— the Stalker himself reckons that it is only the most wretched and hopeless who are allowed in. Certainly, the overgrown wreckage of the tanks and howitzers left over from the army’s disastrous foray into the Zone suggests that the powerful aren’t welcome there. But then again, we in the audience never see a single goddamn thing to distinguish the Zone from any other pocket of wilderness which nature has reclaimed from its former human owners. For all the Stalker’s talk, neither the wonders of the Zone nor its terrors ever put in an appearance.

What I kept thinking about while watching Stalker was Eric Cartman’s description of art films in that old “South Park” episode— nothing but gay cowboys sitting around eating pudding. And honestly, Stalker would have been far, far more enjoyable if that’s what it really had been about. We’ve now reached the point in the film at which the Stalker, the writer, and the professor embark on a 90-minute argument about the meaning of life. Heaven preserve us! First they argue about the meaning of life by a brook. Then they argue about the meaning of life on a hill. Then they argue about the meaning of life in the woods. In a cave. In a drainage pipe. In an abandoned building. Whine, whine, whine. Bitch, bitch, bitch. Angst, angst, angst. “I’ve lost my inspiration,” “I’m so lonely,” “I’m so miserable.” Yeah? Well none of those ass-munchkins is anywhere near as miserable as I was listening to their tiresome, tedious windbaggery for a fucking hour and a half! When the professor finally revealed that he wanted to come to the Zone so that he could destroy it with the twenty-kiloton nuke he’d been carrying in his knapsack the whole time, I just about stood up and cheered. What stopped me was the knowledge that there were still a good 25 minutes of movie left...

Okay, sure. Stalker is pretty to look at. And in contrast to the situation in Solaris, there is an immediately comprehensible reason why the film stock changes back and forth between color and black and white: color for the Zone, monochrome for the city. Stalker even becomes mildly interesting from a sociological/historical perspective, in that it was surely not accidental that the characters’ efforts to get into the Zone (and what they hoped would happen to them once they did) so closely parallel the ordeal of escaping from behind the Iron Curtain. For that matter, the despair and disillusionment that greet them at the very threshold of the Room was surely not accidental either; Stalker was produced by the Soviet state-run studio Mosfilm, so Tarkovsky could scarcely get away with making so obviously symbolic a movie unless it lacked a conventionally happy ending. But none of these things absolves Stalker of its central sin: it is a deadly dull film, and would have severely taxed my patience at even half its inexcusably bloated running time.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact