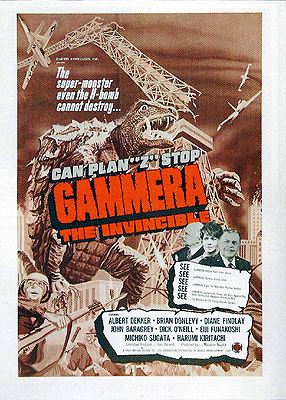

Gammera the Invincible (1966) -**˝

Gammera the Invincible (1966) -**˝

As everyone knows, American moviegoers went mad for giant monsters in the 1950’s, and Hollywood indulged their emergent appetite on an aptly monstrous scale. Resuscitated dinosaurs, titanic apes, gargantuan sea beasts, and overgrown bugs of every description rampaged across the silver screen for a decade and more, combining and recombining with the full array of other hot topics in horror, sci-fi, and fantasy adventure cinema. And as everyone also knows, the mania quickly spread abroad, where it took root most firmly in Japan. Japanese monster movies, or kaiju eiga, then got exported back to the West, where they did just as big business for a time as their American counterparts. But by the mid-1960’s, fatigue was setting in pretty much everywhere but Japan, and even the Japanese market for movies about humongous monsters was undergoing important demographic and economic shifts. Some measure of kaiju eiga’s declining stock overseas may be taken from the fact that Destroy All Monsters was the only Godzilla movie to play in mainstream American theaters during the back half of the decade, although Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster and Son of Godzilla did get picked up for broadcast on US television.

Daiei, in other words, faced a very different environment when it got into the kaiju business in 1965 than Toho had eleven years earlier. There was still enough interest at home for the studio’s Gamera films to compete with Godzilla by keeping production costs strictly controlled, and by consciously targeting a younger audience, but bookings abroad proved much harder to come by— especially in the United States, the most lucrative export market of all. Indeed, only the inaugural entry in the series made it to the big screen here, with the sequels up to 1970 all going straight to TV. Also, when Gamera arrived in American theaters as Gammera the Invincible in 1966, it did so in strikingly altered form. It wasn’t just all the new footage with American actors shot by then-obscure television jobber Sandy Howard that re-centered Gammera the Invincible, either. To the maximum extent possible, American International Pictures toned down all the quirks that had made Gamera so endearing in its original guise. Whereas the Japanese cut twisted the familiar old monster-rampage formula into something wonderfully strange and confusing, Gammera the Invincible really is just a lousy ripoff of Godzilla: King of the Monsters.

1966 seems awfully late to go searching for the Northwest Passage, the longed-for navigable route through the Arctic ice that so captured the imaginations of 19th-century explorers, but that’s what the Japanese oceanographic survey ship Chidori Maru is doing. So far, though, all the crew and passengers have found is a friendly but little-studied Eskimo tribe with some interesting old artifacts in the chief’s igloo— not that it matters, since the vessel’s official mission is just pretext anyway. In plot terms, the Chidori Maru’s true purpose is to provide witnesses to the scariest confrontation between the superpowers since the Cuban Missile Crisis, and to that confrontation’s weirdest and ultimately most devastating after-effect. While lead scientist Dr. Hidaka (Eiji Funakoshi, of The Old Temple Well and The Ghostly Trap) is chatting with the Eskimo headman (Yoshio Yoshida, from The Ghost Ship, Part 1 and Zataoichi on the Road) about a curiously carved stone, accompanied by his assistant, Kyoko (Harumi Kiritachi), and a reporter named Aoyagi (Junichiro Yamashiko), and while the ship herself is crunching her way through the ice to create a route for the next leg of the voyage, a quartet of Soviet bombers streaks overhead into regions of the sky where no Soviet bomber ought to venture.

Naturally, the incursion comes to the attention of General Arnold (Brian Donlevy, from The Creeping Unknown and The Curse of the Fly), commander of an Alaskan outpost of Air Defense Command. Naturally, Arnold orders a squadron of his interceptors aloft at once to deal with the situation. And naturally, neither set of pilots greets the other warmly when they come into contact. Before you know it, air-to-air missiles are flying back and forth, one of the bombers goes down in flames, and the remaining three turn tail for Siberian airspace with Arnold’s jets hot on their heels. The crisis isn’t over yet, though, for when the stricken bomber hits the ice below, something triggers the fuse of its atomic payload, causing a tremendous explosion. Both the Chidori Maru and the Eskimo village are too far away to be in any direct danger from the nuke blast, but the heat penetrates deep into the icepack, thawing out and reviving… wait— is that a turtle?! A 200-foot, bipedal, tusk-toothed, fire-breathing turtle?!?! The monster waylays the survey ship, destroying her and killing everyone aboard before disappearing with inexplicable speed and totality. The Eskimo chief then fulfills his true function in the narrative, identifying the turtle-thing as Gammera, a creature out of his people’s mythology.

The most interesting detail difference between Gammera the Invincible and Gamera arises now, as the outside world devotes the lion’s share of its attention to the looming threat of nuclear holocaust, and treats reports of a monster from beneath the ice as silly tabloid bullshit. We even get a clip of some TV talk show in which a university professor (immensely prolific cartoon voice actor and TV guest star Alan Oppenheimer, best remembered today as the voice of Skeletor on “He-Man and the Masters of the Universe”) who cautions that the Gammera menace ought to be taken seriously gets shouted down by an arrogant naysayer (Mort Marshall, from Skullduggery and Target Earth). Eventually, however, the Proper Authorities— represented by the US Secretary of Defense (Albert Dekker, of Dr. Cyclops and The Last Warning), Senator Billings (Steffen Zacharias, from The Conspiracy of Torture and What Have They Done to Your Daughters?), and General Arnold’s superior, General O’Neill (Dick O’Neill, of Wolfen and The Ghosts of Buxley Hall)— satisfy themselves that the Alaska Incident was just an unfortunate misunderstanding. Some Russian pilots on a routine training exercise wandered offcourse, and things got out of hand. (And even if neither side really believes that, both of them agreeing to pretend to is obviously preferable to the alternative!) The military stand-down occurs just in time to redirect the effort that humanity might have spent on exterminating itself toward dealing instead with Gammera— who does indeed exist, as Dr. Hidaka can attest, and who is in fact fixing to make trouble in more populous regions of the globe.

Although Sandy Howard added a lot of new material to Gammera the Invincible, he didn’t add enough to change the essential shape of the story. Gammera still destroys industrial site A, defeating in the process military force B and withstanding massive electrical shock C, then moves on to smash densely populated city D before succumbing at last to whiz-bang high-tech gadget E. What’s different is how emphasis is distributed among the various subplots threaded though that action. Howard tries very hard to convince us that everything is being done at the behest of his politicians, diplomats, and military brass, who of course were not originally in the film at all. This is not nearly as successful a pretense as Joseph Levine’s insertion of Raymond Burr into Godzilla: King of the Monsters as a privileged but uninvolved observer. It leaves the viewer actively wondering about the continued involvement of Dr. Hidaka and his entourage, who after all have no credentials for sticking around beyond that they were all on the scene when Gammera was awakened. The Sakurai family (You remember them from Gamera, right? The lighthouse keeper and his turtle-obsessed little brat?) have meanwhile been minimized as much as possible. Gammera the Invincible treats them basically as displaced persons who coincidentally keep showing up wherever the next act in the larger drama is destined to play out. One result of all this meddling is that Gammera the Invincible no longer seems to be anybody’s story on the human scale, which is even less satisfactory than Gamera’s bizarre determination to be about the Sakurai child in preference to all the more plausible potential protagonists.

The other, even more conspicuous result is that Gammera the Invincible is a much more conventional monster movie than its purely Japanese parent. That’s something that it comprehensively sucks at being, too, even if we disregard all the idiosyncratic defects and defective idiosyncrasies carried over from Gamera. Original director Noriaki Yuasa and original screenwriter Nisan Takahashi had been absolutely right that the mid-1960’s were no time to be making yet another straightforward riff on The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, even if they weren’t right about much of anything else. Only in two places does this version replicate under its own power the sheer lunacy characteristic of the Gamera series back home. First, Gammera the Invincible overwrites the monster’s impressively bonkers origin as an inhabitant of Atlantis with pseudoscientific argle-bargle at least equally bonkers in its own way. At one point, Hidaka calls on a colleague of his (Jun Hamamura, from 100 Monsters and Ghost Story of Devil’s Fire Swamp), who explains Gammera’s invulnerability and strange physiology by proposing that he’s a silicon-based lifeform from the era predating the Oxygen Catastrophe! And later, during the attack on Tokyo, the band at the nightclub which the monster incinerates is re-dubbed so that they’re actually singing about Gammera at the time. What makes the audio substitution truly startling is that the new song sounds like a tepid rock-and-roll arrangement of the “Gamera March” (come on, sing it with me: Tsuyoizo Gamera! Tsuyoizo Gamera! Tsuyoizo Ga-me-raaaaaaaa!), but that justly infamous ditty wouldn’t debut until two years later, with the fourth film in the series. In any case, there’s still a certain amount of cockeyed entertainment value to be mined from Gammera the Invincible, but it comes nowhere close to equaling the screwball charm of either the unadulterated Japanese Gamera or the stunningly craptacular second import version produced for US television and home video by Sandy Frank.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact