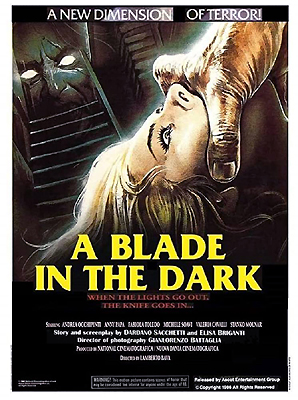

A Blade in the Dark / La Casa con la Scala nel Buio (1983) *½

A Blade in the Dark / La Casa con la Scala nel Buio (1983) *½

I tend to assume that television in Western Europe is less prudish across the board than its American counterpart, for the simple reason that it really is less prudish in so many individual aspects. Like if this French perfume commercial got away with that, and that German prime-time TV movie got away with this, and both of them would have been shot down in a heartbeat on NBC or CBS, then doesn’t it follow logically that the European broadcast rules are just laxer overall? Perhaps. But it doesn’t follow that European TV producers never hear the folks who control the airwaves saying, “You can’t do that on television.” Lamberto Bava’s lumpy but intermittently intriguing giallo, A Blade in the Dark, was originally developed as a four-part TV miniseries, whose half-hour episodes would each climax with a lurid murder. As it happened, though, those murders were deemed a little too lurid for the small screen, even in Italy. Faced with the choice of toning down the shocks or re-editing the miniseries for theatrical exhibition as a feature film, Bava and his co-producers, Mino Loy and Luciano Martino, took the latter route. The results are frustrating, in part because the rambling, episodic story structure dictated by the originally intended medium feels repetitive and disjointed when the whole thing sprawls out in one continuous, 108-minute narrative, but also due to some serious inherent defects in the project as conceived.

Three little boys sneak onto the grounds of what could equally well be an abandoned villa or a disused and deconsecrated church, which it’s safe to assume has an unsavory reputation among the local youth. It seems we’re looking at a dare or an initiation of some kind, in which the blond child (Giovanni Frezza, from Warriors of the Wasteland and The House by the Cemetery) is required to venture alone into the lightless cellar, although there’s no indication what he’s supposed to do once he gets there. Visibly frightened, the blond kid hesitates long enough for his fellows to begin chanting that he’s a little girl, until finally he works up the courage to make the descent. There’s a pregnant pause after he vanishes fully into the shadows, and then a scream rings out, a bloodstained tennis ball is hurled up the cellar stairs with greater force than any child should be able to manage, and the other two boys take to their heels.

We all know where this is going, right? It’s 1983, and that’s a textbook “origin of the killer” slasher-movie opening. Ah, but is it the origin of A Blade in the Dark’s killer specifically? In point of fact, what we really just saw was the opening scene of the new giallo from a filmmaker by the name of Sandra (Anny Papa, from The Great Alligator and Ring of Darkness), which she’s screening for Bruno (Andrea Occhipinti, of Conquest and Miranda), the composer whom she’s hired to score the picture. Horror movies aren’t really Bruno’s thing, but that’s exactly why Sandra wants him. She’s hoping his genre-neophyte’s ear will lead him in unexpected directions, giving her latest work a unique voice. Still, she doesn’t want to chance Bruno coming up with something totally wrong-headed, so she’s going Seven Keys to Baldpate on his ass. Sandra has arranged for Bruno to be put up at the remote villa owned by Tony Rendina (Dario Argento protégé Michele Soavi, whose other turns in front of the camera include The Gates of Hell and Endgame), son and heir of an international infrastructure-construction magnate. Rendina will be away in Kuwait on assignment, and Bruno will have that giant, empty, lonely, isolated house all to himself for the duration of his labors. That ought to spook him into the proper frame of mind for the project, don’t you think?

Would you believe Bruno ends up having only slightly more peace or privacy at Rendina’s place than William Magee had at Baldpate Inn? For one thing, there’s a live-in groundskeeper down in the basement, and although Giovanni (Stanko Molnar, from Macabre and Lady of the Night) does his best to stay out of the way, the dude is so creepy that you can’t help but feel his presence. I mean, every inch of his flat is festooned with crass porno pinups, and he keeps a scrapbook of newspaper and magazine murder headlines! Meanwhile, it’s pretty obvious that Bruno also has an unseen prowler to contend with, because while he’s in another part of the house taking a break from his labors one night, somebody slips into the room where he’s set up his recording studio, pilfers a retractile utility knife, and takes a moment before running off with it to slice up the magazine on Bruno’s desk, which was lying open to an advertisement featuring a topless woman. Let’s face it— whatever else Giovanni might get up to, he certainly isn’t going to deface a pair of knockers like those! (Besides which, nobody that obviously disturbed or disturbing is ever the real killer in a giallo.) Another strange thing that happens that same evening (although it takes Bruno a while to notice) is that one of the composer’s microphones picks up a woman whispering something about someone named Linda having a secret. And then, when Bruno goes to investigate yet more odd noises from elsewhere in the house, he encounters the whisperer herself, hiding in one of his closets. Her name is Katia (Warriors of the Year 2072’s Valeria Cavalli), and if you can believe anything you hear from such a manifestly untrustworthy source, she’s Bruno’s neighbor from across the street. Bruno can get nothing more out of her, though, least of all a credible accounting of why she was snooping around his house like a half-assed cat burglar. Still, for a while there, it looks like the composer might have made a new friend against his will— but then Katia slips away as stealthily as she arrived, and with just as little evident motive. Bizarrely, though, she left her diary in the closet where she’d been lurking earlier, and it’s full of cryptic nonsense about that same Linda, whoever she is. Between the diary, the fortuitous whispers on the tape, and the work he actually came to the villa to accomplish, Bruno is kept busy enough for the rest of the night that he completely misses Katia getting stalked-and-slashed in his own backyard, with his own stolen utility knife.

A call to Tony Rendina in the morning answers at least two of Bruno’s proliferating questions: Linda was Tony’s previous tenant, and the locked room in the basement that the composer found when he moved in is full of her stuff, as if she were planning on returning someday. On the other hand, new and substantially more ominous mysteries arise when Bruno finds a trail of Katia’s blood on his patio and basement stairs, and when he discovers that somebody has destroyed not only the pages of the diary mentioning Linda, but also his tape of the previous night’s recording session. He therefore has little concrete proof to offer his TV actress girlfriend, Julia (Lara Lambretti, of Red Sonja and Zombie 3) when she drops in for a surprise visit, and takes offense that his mind seems to be on something other than her. Far from consoling him over his alarmingly weird experiences at the villa so far, Julia tells him that working for Sandra is messing with his mind, and then goes so far as to pitch a jealous snit over Bruno’s concern for the vanished Katia.

I’m sure she’d be even more jealous if she were still at the house the following afternoon, when Katia’s roommate, Angela (Fabiola Toledo, from Demons and Caligula: The Untold Story), comes over and helps herself to the villa’s swimming pool. Evidently this was a longstanding arrangement that she and Katia had with Linda, and Bruno, fool that he is, sees no reason to discontinue it. He’ll feel differently that night, however, when he finds a whole bunch of the girl’s broken teeth in one of the bathroom sinks, a souvenir of her bludgeoning death at the hands of the composer’s sneaky other visitor. That happened while Bruno was away at the film studio for a meeting with Sandra, but we got to see it, and we therefore know a couple things that our… let’s be charitable, and call it “selectively perceptive?”… protagonist does not. First off, to judge from the killer’s voice, we’ve got one of the surprisingly common female Black Glovers on our hands. And to judge from how she freaked out immediately after bashing Angela’s head against every solid porcelain fixture in that bathroom, she commits her murders in a fugue state during which she has little or no conscious control of her actions.

Meanwhile, it’s looking increasingly like Sandra’s incomplete giallo is somehow the key to this whole bloody mess. For one thing, it turns out that Sandra and the mysterious Linda go way back, and that some of the events in the movie were inspired by things that happened to the latter woman. Sandra even goes so far as to phone Linda to protest that she hasn’t really betrayed her secret, and that no one will be able to put it together solely on the basis of the film. That would seem to suggest that Sandra is a step ahead of Bruno in understanding what’s going on here, and it might also explain why the director has been at such pains to prevent anyone from seeing the tenth and final reel of her picture before its public debut. If so, the smart money’s on Sandra becoming the victim in what was meant to be the climax to Episode 3, leaving poor, witless Bruno on his own to untangle the mystery in spite of Julia’s continued and increasingly petulant efforts to dissuade him from involving himself.

Trickery and misdirection are the soul of the murder mystery. And since gialli are descended from murder mysteries, it stands to reason that they’d rely heavily on those techniques as well. It’s possible, however, for a trick to succeed too well for the trickster’s own good, and A Blade in the Dark is a case study in that phenomenon. The opening scene is transparently the setup for a variation on Norman Bates and his mother, with a killer who’s either a mad transsexual or a multiple-personality case whose murderous persona is of the opposite sex from their public-facing self. But once that preface stands revealed as part of a film within the film, all bets based on it are obviously off, right? Up until Angela’s death, this movie does indeed seem to be straying further and further from the templates of Psycho and Dressed to Kill, so that A Blade in the Dark’s halfway point found me pleasantly befuddled as to where the film could possibly be headed. The third and fourth acts, however, lead circuitously back to the ostensibly false promise of the misogynistic kids and the spooky basement. In the final assessment, it’s a long and winding journey just to end up exactly where I figured we’d be going in the first place.

That might have seemed less of a letdown if the story were presented as originally intended, in half-hour installments over the course of a week or a month or whatever. Indeed, if Lamberto Bava played his cards right under those circumstances, the double fakeout might even have felt like the Hand of Fate at work. A Blade in the Dark is full of such vexing “might haves,” too, stemming directly from its hasty conversion from TV miniseries to feature film. Like it might not have been so obvious that Bruno’s oft-voiced agitation over the prospect of murders being committed in and around his borrowed house never leads him to do anything sensible about it, like, say, calling the police. The late subplot about Bruno beginning to wonder if maybe Julia could be the killer might not have looked so blatantly absurd if we had to think all the way back to what we saw yesterday or last week, in order to recognize that it comes basically out of nowhere, and doesn’t match up with anything we’ve seen thus far. And I’m quite certain that the similarities of structure and rhythm recurring throughout the four acts would have a completely different flavor if they had each been presented separately— resonant instead of merely repetitive, cyclical instead of merely circular.

What the miniseries format would absolutely not have helped, however, is the fundamental emptiness of A Blade in the Dark. In the end, this movie is little more than a regurgitation of nifty things that Bava must have seen in earlier, better mysteries, thrillers, and psycho-horror flicks, with only the bare minimum of original material to hold it all together. Look closely and you’ll see not only the influence of Psycho and Dressed to Kill, but also nods to Blow Out, Blow Up, Diabolique, The Cat o’ Nine Tails, and maybe even a couple truly oddball deep cuts like 5 Dolls for an August Moon and Terror. To be fair, that’s been a tendency in giallo from the very beginning— from before the beginning even, if you want to extend consideration to The Evil Eye. Nearly as long established in the genre is this movie’s other insuperable defect, the insufferable characters played by numpties who could just about manage a facial expression if you dropped a claw hammer on their big toe. But the typical 70’s spaghetti-slasher has something to counterbalance those faults that A Blade in the Dark lacks completely. Even the absolute fucking turkeys of that era (think Torso or Deep Red) could be counted upon to ooze visual style out of nearly every frame. A Blade in the Dark looks like the TV production it originally was, with nothing to appeal to the eye beyond the occasional well-composed shot of the villa and some effectively ominous closeups on the blade ratcheting out of the killer’s utility knife during the stalking of Katia early on. That isn’t nearly enough to justify spending this much time with Bruno and Julia, believe me.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact