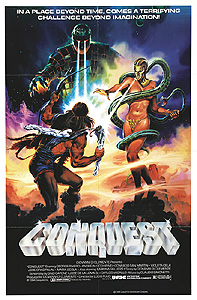

Conquest (1983/1984) -***

Conquest (1983/1984) -***

I’ve mentioned before that during the summer after my junior year of high school, I went on a months-long barbarian bender, watching every 80’s sword and sorcery movie I could get my hands on, and inflicting the ones that especially struck my fancy on as many of my friends as I could convince to watch them. That summer was the first time I saw Lucio Fulci’s Conquest, marking the beginning of a long and somewhat troubled relationship. My first impression was that Conquest was a terrible disappointment, and frankly pretty boring. But then I found myself one day trying to explain it to somebody, and the more I talked, the more I wanted to see it again. I believe I went out to the video store to rent it that very night (it was in stock, obviously— who the hell else would have wanted it?), and while it was still a terrible disappointment and frankly pretty boring, I saw some things the second time around that had escaped my notice initially. I’ve felt myself compelled to watch Conquest several times more since then, and on each occasion I’ve spotted more little details to improve my opinion of it slightly— even as on each occasion, it’s been a terrible disappointment, and frankly pretty boring. It’s now reached the point where I’ve concluded that Conquest really ought to have been a nearly brilliant film, and I’ve developed an unhealthy fascination with all the myriad ways in which it fails to be one.

Take the very first scene as an example. A bunch of people are gathered on a lonely-looking stretch of beach to witness the headman of their tribe giving a pre-quest pep talk to Illias (Andrea Occhipinti, from New York Ripper and Bolero), a lad about to venture into the hostile outside world and make a hero of himself. Why exactly Illias is doing that is never quite clear. Sure, the chief talks a lot about Kronas, who long ago defended the tribe’s land against invading fiends from abroad, and sure, he even gives Illias the legendary hero’s bow (which is supposed to be able to cast Magic Missile when wielded by a warrior worthy of the sun god’s favor), but there’s no indication that these people are under any particular threat now, and Illias will evidently spend quite a while wandering aimlessly in the wilderness before a situation requiring the attention of a hero comes to light. It’s impossible to say for certain without asking any of Conquest’s several screenwriters whether that was supposed to be a sidelong comment on the vagueness of motivation that so often bedevils heroic fantasy (later developments will suggest that such a thing is legitimately possible), or just a mammoth oversight in the script. In any case, we’ve been offered no good reason as yet to extend Conquest the benefit of any doubts whatsoever, so the timing has to be considered poorly chosen even if we agree to accept the more laudable explanation. Meanwhile, Fulci and cinematographer Alejandro Alonso Garcia play an odd visual trick with this scene, shooting the actors in double exposure, through the thickest scrim even slightly compatible with producing an intelligible image. Here, the intent is obvious; Fulci want us to see at once that the movie is set in a past so remote that no tangible trace of it remains, leaving the garbled accounts of legend and mythology our only means of accessing it. Unfortunately, what it really looks like is a novice filmmaker’s first experiment with sleight-of-camera techniques that he’s read about, but has never been properly shown how to use. Garcia had been a cameraman since 1949, and a director of photography since 1957, while Fulci had been directing in some capacity or other since 1950, when he served as assistant director on The Last Days of Pompei. It’s simply astonishing that two men with nearly 80 years’ experience between them could fail so completely to create the image they sought when using techniques first developed in the 1890’s! The botched opening scene might as well be Conquest’s formal mission statement, too, for its stark dissonance between clever concepts and shockingly amateurish execution is the defining trait of the entire film. The action will become more opaque after the credits (I mean that literally in this case, although the obvious figurative reading would just as be accurate), but it never gets any less ugly or cheap-looking.

That hostile outside world into which Illias is venturing is a curious place, even for an 80’s sword and sorcery flick. On paper, it’s really quite fascinating. The would-be hero’s tribe is clearly the most advanced in the vicinity, to the extent that Conquest often looks as much like a caveman movie as it does a barbarian film. (None of the people Illias meets on his rather shapeless quest have ever so much as heard of a bow, for example.) The local stone-agers are tyrannized by a priestess-sorceress named Ocron (Sabrina Siani, of White Cannibal Queen and 2020 Texas Gladiators), who claims to control the rising and setting of the sun, and who unambiguously does control an army of wolf-men and human savages. Ocron’s domain is also home to a whole Monster Manual’s worth of ever-weirder creatures— mud zombies, cobweb people, glowing-eyed shag beasts, even something that I take to be an attempt at a manticore— all of them beholden somehow to an evil godling called Zora (who’ll be played by Conrado San Martin, from The Awful Dr. Orlof and Edge of the Axe, when he puts in a personal appearance later). And in one of the movie’s more intriguing subtle background touches, it is strongly implied that although Ocron’s magic is indeed real, the religion she has cultivated around herself as mistress of the sun is as big a con-job as any real-world faith.

Anyway, we first see Ocron from the perspective of a lice-ridden prehistoric rabble gathered at the foot of a cliff in the moments before sunrise. The sorceress, accompanied by an honor guard of wolf-men and emphasizing the solemnity of the occasion by adding a cape of raven feathers to the gold mask and g-string that normally comprise the whole of her costume, perches on the highest point of the escarpment and intones the chant that supposedly brings on the dawn. At the rite’s conclusion, Ocron sends the wolf-men down to a cave where some of her subject-worshipers live in order to collect the fee for her celestial services. It’s apparently been a lousy season for hunting and gathering thus far, and when the cave-dwellers are unable to offer up a satisfactory quantity of food in tithe to their ruler, the wolf-men claim instead a human sacrifice. The girl is dismembered on the spot, and the next thing we see, her head is presented to Ocron, whose favorite dish is apparently raw human brains, straight from the cranial cavity. Then the priestess and her minions all get high together on some weird hallucinogenic drug.

Ocron does not have a pleasant trip. Her hallucinations show her a man with no face, who infiltrates her subterranean stronghold and shoots her through the heart with a ray of blue light fired from his bow. Ocron takes the drug-induced vision as a portent of her future, and she understandably orders all of her soldiers to be on the watch for an outsider carrying a strange weapon.

That brings us back to Illias. He makes his first attempt at doing something heroic when he “rescues” a cute, teenaged cavegirl (Gioia Scola, from Raiders of Atlantis and They Only Come Out at Night) from “attack” by a large but patently harmless snake. Though plainly grateful for Illias’s intervention, the girl plays hard to get, running off into the surrounding swamp with much smiling, giggling, and fluttering of eyelashes. Illias is prevented from giving chase, however, by a squad of Ocron’s soldiers, who were apparently assigned to cock-blocking detail this morning. Even so, Illias has it all his way at first, with several of his attackers falling in rapid succession to his adept archery. The trouble is, Illias has brought with him just five lousy arrows, which is about half what he’d need to deal with the present situation assuming even the best shooting. All the signs point to Illias receiving a truly epic drubbing, but then along comes Maxz (Jorge Rivero, of Evil Eye and Neutron Traps the Invisible Killers) out of absolutely fucking nowhere. Maxz is a wandering barbarian bad-ass much like Illias aspires to be, only he’s a lot better at it than the younger man is at present. Despite carrying no weapons more formidable than a pair of bone-and-twine nunchaku, and despite receiving no help at all from the incapacitated Illias, Maxz annihilates Ocron’s patrol, leaving only one man alive to limp home to his mistress and report on the encounter. Ocron, who did not become an all-powerful witch-queen by being a dumbass, susses out at once the connection between her earlier vision and this stranger whose weapon slays from afar with the speed of the wind.

But to return to Maxz for a bit, it’s tempting to look at him as the Han Solo to Illias’s Luke Skywalker. Illias may be the one on the big destiny trip, but you won’t have to watch for long before deciding that Maxz is the one you’d rather have backing you up in a fight. That said, he’s no more motivated by principle than the more famous Corellian space pirate, so actually getting any such backup from him might take some doing. Illias first finds that out when he thanks Maxz for saving him, only to have the burly barbarian reply that he was really trying to save the boy adventurer’s bow. He’d hate to see something like that fall into anyone’s hands but his own, and he expects Illias to instruct him in its use as compensation for the incidental rescue. That’s just the start of Maxz’s eccentricity, too. He claims to have no friends among men, pointing to the squiggly brand on his forehead as if it explained everything. (That non-explanation will be just a tiny bit less cryptic to those who have seen The Beyond. The sign burned into Maxz’s forehead appears in that film as the Mark of Eibon, a symbol associated with one of the seven gateways to Hell.) Instead, Maxz keeps the company of wild animals— bats, snakes, dolphins, you name it— demonstrating that somebody involved in Conquest’s creation has seen The Beastmaster. Perhaps that affinity for animals is also related to Maxz’s weirdly casual yet completely non-malicious approach to murder, as when he practices the archery Illias teaches him by shooting down a hunter returning home with his prey, and then appropriates the dead man’s game for his and Illias’s consumption instead. All in all, Maxz has to be considered a very unconventional second-banana good guy.

Despite his generally hostile stance toward his fellow men, however, Maxz plainly has an altogether more favorable opinion of women, for the first place he takes Illias is a cave inhabited by his favorite local booty call, her little sister, and a couple of children whom we may surmise to be the product of the nomadic warrior’s previous visits. Little Sis, as it happens, is the girl Illias met out in the swamp the other day, and things are looking extremely conjugal for the two youths by the time their elders have fallen asleep by the campfire. This is a Lucio Fulci movie, though, and in Lucio Fulci movies, few things ever turn out as nicely for the protagonists as we’d normally expect. Ocron has sent more soldiers out to capture Illias and his bow, and they descend upon the women’s cave literally just as Fulci is setting up what we think is going to be a love scene. The regular inhabitants of the place are all slaughtered, Maxz is knocked senseless, and Illias is carried away, trussed up to a pole like a wild hog.

Maxz recovers quickly, though, and with a little help from his animal friends, he overtakes Ocron’s troops before they’ve reached their destination. You know, for a guy who claims that all men are his enemies, he sure does spend a lot of time saving Illias’s ass… This time, Maxz is his usual victorious self, and more importantly, he reveals the identity of the assailants’ employer when Illias understandably asks what the hell was up with the unprovoked massacre and attempted abduction. Maxz cautions Illias that Ocron is out of his league, but overthrowing evil magicians is exactly the sort of action that Illias was seeking when he set out from his homeland with the Bow of Kronas. Ocron, for her part, also decides that the time has come to get serious. After making an example of the wolf-man who led the failed kidnapping mission by frying him alive on a giant stone griddle, she steps up her prophecy-thwarting endeavors by summoning Zora from the underworld, and offering her body and soul in exchange for the mysterious foreign archer’s death. The terms of the trade sound pretty good to Zora, and killing one little mortal ought to be no sweat for a demon-deity, right?

I’m about to spoil the biggest and most interesting surprise that Conquest has to offer, so if you haven’t seen it yet, but think you might want to, here’s your chance to skip ahead to the next paragraph. Right, then. Those of you who are still with me may have noticed a curious contradiction at the center of Conquest’s story as I have thus far recounted it. On the one hand, we have a fairly generic Hero’s Journey thing going, with a callow youth setting off on an adventure that might be rather too big for him, and facing a succession of trials that look calculated to forge him into a man the equal of his mission. On the other hand, Illias gets every square inch of his ass kicked each and every time the bad guys put in an appearance, and Maxz ends up doing all the hard work. Even the one time Illias comes to Maxz’s rescue, turning back to free him from the clutches of the cobweb people after an especially close brush with death temporarily convinces Illias to emulate the valiant chickening out of Brave Sir Robin, he still can’t quite get it right. He wins the sun god’s favor with his return to the fray, and accesses the magic of Kronas’s bow, but his wholesale slaughter of the cobweb people comes too late to prevent them from tossing the crucified Maxz off the top of the sea cliffs where they dwell. Illias may do the fighting this time (and do it really well for once), but the actual rescue is effected by a couple of Maxz’s dolphin pals. And really, you’ll be asking yourself long before that happens why Maxz isn’t the hero of this movie, instead of that good-for-nothing putz with the snazzy bow. Well, guess what… Maxz is the hero! The seemingly obvious implications of Illias’s performance on the sea cliffs are nothing but a setup, and the next time he tangles with Zora’s minions, they fucking kill him!!!! It ends up being Maxz who completes the quest, moved by the spirit of the one man who ever treated him as a friend. If ever there was a more thoroughgoing subversion of the fantasy genre’s most basic formula, I’ve certainly never seen it.

The reason it took me so many years and so many viewings to appreciate fully the value of that gigantic subversion is that so much else about Conquest incontestably is bungled that I honestly wasn’t sure the film’s creators meant to do it. The intent behind Conquest’s third-act slap upside the expectation is rendered suspect first by the frequency with which poorly written fantasy movies straight-facedly present us with heroes who frankly kind of suck. Witness Ator the Fighting Eagle, in which the titular muscleman would be pretty well useless without his pet bear, or Clash of the Titans, in which one of the deadliest of the Greek demigods (Mama didn’t name him Perseus— “Destroyer”— for nothing) is made dependent to an indecent degree upon the assistance of a magical clockwork owl. But even without that context whispering in your ear, there are more than enough fuck-ups here to permit a first- (or second-, or third-) time viewer to assume that the one thing Conquest gets really right is just one more of the thousand things it gets wrong. Look at the cinematography; between the inadequate lighting, the overachieving smoke machines, and the goddamned Super Scrim, you can just barely see what’s going on half the time. Consider the special effects: the wolf-men who look like upscale Halloween costumes, the manticore (or whatever) represented solely by a rustling in the underbrush and a torrent of flying “quills” literally scratched into the surface of the film, the Ultimate Evil who looks more like the Linoleum God when he isn’t taking the even more unimpressive form of a slobberingly friendly pooch. Pay close attention to the writing that surrounds the climactic switcheroo; challenge yourself to discover a single credible reason for anyone but Ocron to do anything, or a single memorable bit of dialogue apart from, “My enemies call me Maxz.” “And your friends?” “I have no friends.” For all the commendable glimmers of independence and individuality that Conquest displays in defiance of the norms of both its genre and the industry that produced it, this is still a shitty, shoddy movie on the whole. Is it any wonder that its greatest act of creative daring could be so easily mistaken for a mistake?

This review is part of the B-Masters Cabal’s salute to caveman and barbarian movies, those films that did so much to usher cable-enabled boys of my age group into the perpetually suspended adolescence that passes for manhood among us. Click the banner below to read my colleagues’ takes on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact