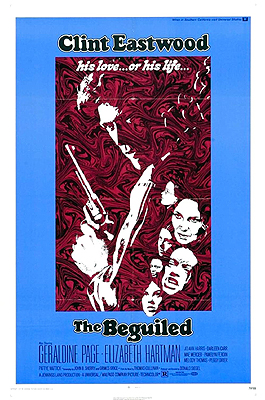

The Beguiled (1970/1971) ****

The Beguiled (1970/1971) ****

As the 1970’s dawned, Clint Eastwood was ready to try something different. Westerns had been very good to him, and he was very good at them, but there are only so many times a man can squint into the middle distance as the prelude to an eruption of gunfire before his acting muscles start to feel cramped. Director Don Siegel was eager for a change of pace, too. Like Eastwood, he’d had a very macho 1960’s, and he was in the mood to try something more feminine. Not necessarily a “women’s picture” in the marketing department sense of that phrase, but something in which female characters drove the action, and in which their perspective would be critical for making sense of the story. Eastwood and Siegel ended up scratching their mutual itch by collaborating on a pitch-dark adaptation of Thomas Cullinan’s Southern Gothic novel The Beguiled. It turned out to be nothing that audiences wanted to see from either man (Siegel blamed the promotional campaign, which he considered misleading and misaimed), but it’s precisely the abnormality of the project that makes it so interesting. Siegel may have intended a feminine film, but what he actually made was the most potent exploration of male psychosexual anxieties since Kitten with a Whip.

Union infantryman Corporal John McBurnie (Eastwood, who would fall into the hands of a dangerous woman again in Play Misty for Me) has been wounded by shrapnel during an incursion deep into Confederate territory. His leg full of holes, his skull concussed, and his hands burned to crisps, he is found in the forest by twelve-year-old Amelia (Pamelyn Ferdin, from The Toolbox Murders and The Mephisto Waltz), the youngest of six students currently enrolled at the Farnsworth Seminary for Girls. It’s quite a quandary for her. On the one hand, McBurnie is an enemy soldier; on the other, he’s also a human being in pain. Further complicating the situation, the corporal strikes Amelia as terribly dashing, even in his current condition, and McBurnie cannily encourages her in that sentiment by kissing her long and insistently enough to keep her quiet while a platoon of retreating Confederate troops pass by his hiding place. In the end, Amelia helps McBurnie to his feet and leads him to the relative safety of her school.

I say relative safety because the Farnsworth Seminary is a nest of Southern plantation ladies in training— hardly a hospitable environment for a wounded Yankee footsoldier. Even Hallie (Mae Mercer, of Frogs and The Swinging Cheerleaders), the academy’s slave housekeeper, is hostile and suspicious, harboring no illusions about what any white man— Northern abolitionists included— thinks of her race. That said, only Doris (Darleen Carr, from The Horror at 37,000 Feet and the “Roger Corman Presents” version of Piranha) has the ideological clarity to advocate handing McBurnie over to the very next military patrol to come round. The other students— together with Edwina the tutor (Elizabeth Hartman) and even headmistress Martha Farnsworth (Geraldine Page, from What Ever Happened to Aunt Alice? and The Birds)— are as uncontrollably fascinated with the injured man as Amelia, and almost immediately begin building elaborate romantic fantasies around their common effort to nurse him back to health. McBurnie, realizing full well that his life depends upon maintaining these women’s goodwill, skillfully sets about discovering how each of them has cast him in her private passion play, and acting as much of each part as he can manage.

This is a perilous strategy McBurnie is pursuing, however. For one thing, the personas he puts forth when he’s alone with each inmate of the Farnsworth Seminary in turn are mutually irreconcilable for the most part: a pacifist Quaker for Miss Farnsworth herself, a fire-breathing abolitionist for Hallie, a war-weary homebody for Edwina, a worldly romantic for Amelia, and a passionate rake for Carol (Jo Ann Harris, from Cruise into Terror and Deadly Games). There’s an upside to such multiplicity of duplicity, insofar as it lets each of McBurnie’s caregivers flatter herself to believe that she alone has seen into the soldier’s secret heart, but that will work only so long as the women feel inclined to cooperate with their own deception. And that points toward the greater danger for McBurnie. So long as he remains invalid, he can put off having to fulfill any of his nurses’ expectations, but once he’s strong enough to get around the house and its grounds on his own, he’s going to have to start walking the walk (or at least hobbling the hobble). Some indication of what’s at stake comes to light when Carol catches John tarrying in the gazebo with Edwina, and jealously posts the signal that alerts the military patrols to the presence of enemy combatants on or about the premises. McBurnie is just lucky that Miss Farnsworth isn’t done with him yet when a trio of bounty hunters come to investigate. He’s a great deal less lucky when Edwina catches him in bed with Carol— and less lucky still when Miss Farnsworth catches Edwina wreaking her vengeance upon him.

The Beguiled is a superb illustration of how some of the most effective moments of horror in both film and fiction can be found outside what we normally consider the parameters of the horror genre. What happens when McBurnie’s seemingly clever survival strategy backfires on him could teach the makers of Saw, Hostel, Turistas and their ilk a thing or two about how to get full value out of the Captivity & Torment routine. And as the actor himself seems to have intuited, that sharp turn into the darkness is all the more potent because it’s Clint Fucking Eastwood being reduced to helpless victimhood. Indeed, I expect that incongruity has even more impact now than it did at the time, since the definitive Eastwood tough-guy performance was still a few months in the future when The Beguiled premiered. It was shocking enough to see a pack of Southern belles treat the Man with No Name this way, but we know that they’re doing it to Dirty Harry Callahan!

Mind you, it starts to look like these ladies are Bad News long before the razors and hand saws and toxic mushrooms come out. After all, Carol’s jealousy almost gets McBurnie sent to a POW camp, and she isn’t half as bent as the headmistress. McBurnie’s advent at the seminary immediately gets Miss Farnsworth thinking about her mysteriously vanished brother (played in flashback by Patrick Culliton, from The Swarm and Time Travelers), with whom she was having an incestuous affair when he disappeared. (Nobody tell Martha, by the way, but there’s a good chance Hallie knows something about what happened to the missing man.) Miss Farnsworth, as it happens, is craftier in her revenge than Edwina or her pupils, too. Whereas the girls merely lash out, she looks for a way to render John’s dependence on the seminary inmates permanent. Besides, as a dream sequence reveals, Martha isn’t totally opposed to sharing McBurnie, provided that everyone concerned remembers that she’s the boss around here.

That dream sequence points to one of The Beguiled’s more unusual features. Because so much of the action here is critically concerned with the characters’ subjective interpretations of events, Siegel takes pains to make sure we know what everybody is thinking. Sometimes, and rather unsatisfactorily, that means intrusive, Dune-like voiceovers, dropped crudely into the middles of conversations. Other times, it means dream sequences in which the desires and expectations of this or that figure are played out. And on yet other occasions, it means flashbacks. The flashbacks are the most cleverly and skillfully deployed of the three techniques for getting us inside the characters’ heads, for they are triggered not by the mere remembrance of past events, but by secrets and lies. We see Miss Farnsworth romancing her brother whenever Miles comes up in conversation, or whenever some action of John’s reminds her of what vanished from her life along with her lost sibling. The flashback hinting at Miles’s unknown fate comes when Hallie warns a drunken and lustful McBurnie to keep his hands to himself. Best of all, the wounded soldier’s falsified versions of how he came to be in his present predicament come packaged with contradictory flashbacks showing what really happened. The only time I can recall seeing anything similar is in Zombie, where Lucio Fulci suggests that Dr. Menard is lying about what happened to his assistant by showing us the scene twice, first in “truthfully” squalid conditions, and then again in the much cleaner and more orderly surroundings that the doctor would prefer to remember. Siegel’s version of the trick is clearer and more accessible, however. It’s also the surest sign of how he was hoping to expand his repertoire with The Beguiled. Such a pity that audiences of the time weren’t prepared to follow him into this shadowy territory. I’d have liked to see him spend more time there.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact