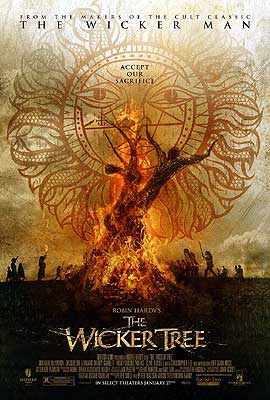

The Wicker Tree (2011) ½

The Wicker Tree (2011) ½

Perhaps you remember the kicking that I and every other reviewer in the known universe gave to Neil LaBute’s majestically stupid remake of The Wicker Man some years ago. What no one realized at the time was that Robin Hardy, writer and director of the original Wicker Man, was capable of doing much worse. Hardy made a 30-years-too-late sequel, you see (assuming it actually is a sequel— we’ll talk about that later), in which he took an epic shit on his own legacy, and proved that he could misunderstand his own work every bit as thoroughly as some upstart American with a bug up his ass about feminism. In a way, you could even argue that The Wicker Tree shows Hardy returning LaBute’s “compliment.” Just as the 2006 Wicker Man’s basal failure was LaBute’s inability to see how the original depended entirely upon the social, economic, and religious circumstances of 20th-century Britain, The Wicker Tree first goes off the rails due to Hardy’s misreading of the same circumstances in 21st-century America.

We begin in the most unlikely place imaginable to launch a sequel to The Wicker Man: Dallas, Texas. At some cheesy Evangelical salvation shed outside the city limits, the congregation’s proudest achievement is that they were the ones who brought pop-country skanklet Beth Boothby (Britannia Nicol) to Jesus, and guided her transformation into a purveyor of Godly classical music.

Okay. I’m going to hit the pause button right here, because there isn’t a single detail of that setup that isn’t somehow wrong. For one thing, Beth Boothby? Seriously? Pop country is all about self-conscious low-caste Americana. The only way “Beth Boothby” could sound more British is if she were Bess Boothby instead. Even if that really were her name, her agent or her record label or somebody would insist that she change it to something like Lizzie Booth. The other thing pop country is very self-conscious about is its pantomime of conservative rural values. Women in that business are allowed to be earthy, but skanky is right out. Note the example of Miley Cyrus, whose enthusiastic embrace of skankhood signaled her abandonment of the pop country format. And when you see the video for Beth’s old top-40 hit, “White Trash Lover,” you’ll be forced to ask whether either Hardy or songwriter John Scott had ever actually encountered a 21st-century pop country tune in the wild. Where’s the steel guitar? Where’s the exaggerated fake Deep South accent? What’s with the sad, Deliverance-y, middle-aged butt-munchers perched on bar stools to either side of Beth while she tries futilely to line-dance without a line? Shouldn’t those guys be hunky young cowboys instead? For that matter, shouldn’t they be her frigging dance partners? And finally, the new Beth Boothby is operating in completely the wrong genre, too. On this side of the pond, the theological associations of classical music are Roman Catholic or mainline Protestant. A conversion like Beth’s implies contemporary Christian music— that is, the same shitty pop she was peddling before, except that instead of singing “I love you, baby— I want you inside me,” she’d now be singing “I love you, Jesus— I want you inside me.”

We’re on firmer ground when it comes to Beth’s relationship with dim yet earnest cowboy Steve Thomson (Harry Garrett, of Visions and Re-Kill). Both are born-again virgins, their commitment to renewed chastity symbolized by the matching purity rings they wear— because as we all know, sex is a filthy, disgusting, sinful, perverted business, and that’s why you must save it for the person you join in holy matrimony. Anyway, the pastor at Beth and Steve’s church has recruited them for missionary work among the heathens of Scotland, which raises so many questions that The Wicker Tree has no intention of ever answering. The most interesting interpretation minimally supported by the text is that word of the Summerisle pagans has finally gotten out to the world at large, and that the pastor realizes what he’s sending his protégés into (even if they themselves have no idea). But it could equally well be that this bunch consider anyone who doesn’t subscribe to their specific brand of King James-only, Young Earth creationist, socially conservative, politically right-wing, fundamentalist Protestant Christianity to be heathens, since that sort of thinking is not at all uncommon in the milieu we’re talking about here. Either way, Beth and Steve will travel to the village of Tressock, where they will stay as guests of Sir Lachlan Morrison (Graham McTavish, from Pandemic and The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey) and his wife, Lady Delia (Jacqueline Leonard). With the manor house as their base of operations, the two kids will God-bother every one of the Morrisons’ tenants, both door-to-door and by means of a concert staged in their hosts’ great hall.

Now The Wicker Tree is cutesie-poo coy about back story, but Sir Lachlan is the son of a guy who looked remarkably like the third Lord Summerisle (played in supremely pointless flashback by a slumming Christopher Lee). If in fact that makes Morrison the fourth Lord Summerisle, then he fits into the family’s ideological evolution in an intriguing way. Looking back to The Wicker Man, you’ll recall that the founder of the lineage reintroduced Celtic paganism as part of a wide-ranging program of social reform, aimed at improving the degraded lot of the peasants who worked his land. He took a cynical attitude toward the truth content of his religion, but a utopian one toward its value for the wellbeing of his tenants. His son, however, was brought up a true believer, and remained one until he died. And the Lord Summerisle we know, who may or may not have been Sir Lachlan’s dad, was a pragmatist agnostic about the gods but committed to the society and culture that belief in them supported. Sir Lachlan, though? He’s a grifter pure and simple, a neo-Druidic Franklin Graham unscrupulously exploiting his family legacy of spiritual authority to cover the shady behavior that lines his pockets. Specifically, he’s using it to cover the Nuada Nuclear Plant, an undertaking that would have horrified his nature-venerating ancestors, and which has so poisoned the local groundwater than just one child has been born in Tressock during the past fifteen years.

Yeah, I think we know why Beth and Steve are really here, don’t we? But before they suffer whatever fate befalls human sacrifices in this not-quite version of Summerisle, it’s obviously imperative that Steve impregnate or that Beth be impregnated by one of the villagers. That’s where Lolly (Honeysuckle Weeks), mistress of Sir Lachlan’s stables, comes in. Her skill in the riding and care of horses is obviously a sure source of appeal for a cowpoke like Steve, and she’s certainly easy enough on the eyes. Easy in other ways, too, as she personifies more than anybody else the Tressockers’ relaxed attitudes about sex. So basically she’s The Wicker Tree’s Willow, except that whereas Willow’s temptations were expected (or at least hoped) to fail, confirming Sergeant Howie’s suitability as a sacrifice to the gods, the plan here is for Lolly to get Steve all the way into her pants as quickly as possible. Then the people of Tressock can safely dispose of him in a needlessly convoluted ritual bloodletting that feels considerably less plausibly Celtic than its counterpart in the last movie. Even that is easier to swallow than what lies in store for Beth, however. Her intended fate owes less to Druidic religion than to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

The making-of featurette on the Wicker Tree DVD is probably the most illuminating supplement to a truly terrible movie that I’ve seen since the invaluable extras appended to Uwe Boll’s House of the Dead. They’re illuminating in much the same way, too, exposing the misconceptions that enabled the films’ respective creators to suck with more than ordinary might. In this case, we learn that Robin Hardy has come in retrospect to the astonishing conclusion that The Wicker Man is best understood as a black comedy. Look— I get it. It’s his movie, and he can relate to it however he wants. But a comedy? Really? Is Hardy sure he isn’t confusing The Wicker Man with Hot Fuzz? Wherever he picked up that baffling notion, The Wicker Tree was unmistakably made in accordance with it. Thus the people of Tressock are spoooooky pagans instead of just somewhat ornery country folk with some peculiar ways. Thus the eventual battle between Beth and the villager charged with taxidermizing her has a strong splatstick flavor, attempting to wring humor out of both genital violence and the Scottish tradition that thou shalt not wear underpants with a kilt. Thus we must endure a tedious detour through sex farce territory when Lolly pays a visit to her cop boyfriend before committing whole hog to the seduction of Steve Thomson. Unsurprisingly, none of it is funny, and most of the gags seem pointlessly mean-spirited on top of it all. It’s hard to put my finger on how exactly, but it has something to do with the way Hardy treats Beth. A comparison with The Wicker Man is helpful here. However far out of his depth he turned out to be on Summerisle, Sergeant Howie was ultimately a figure of authority, and one who reflexively wielded his authority as a cudgel. Consequently, it was fun watching Lord Summerisle and his people put one over on him— at least until it became clear how grimly high the stakes were. And of course Howie gave almost as good as he got right up to the end. Beth Boothby, on the other hand, is just a naïve kid, and she’s already had several put over on her before she ever sets foot in Scotland. Sir Lachlan and his followers are engaged in a battle of wits against a disarmed opponent. For Hardy to invite laughter at her plight, too, just feels gratuitous. His misapprehension of redneck culture and spirituality plays a role as well, because it tends to turn Beth into a nasty stereotype of something that doesn’t even really exist.

Another major problem with The Wicker Tree is its almost shocking junkiness. The video cinematography looks like something out of a daytime soap opera. The sets, props, and costumes are cheap and shitty without feeling homemade the way their counterparts in the previous film did. The cast apart from Christopher Lee and Graham McTavish is community theater at best, and high school drama club at worst, with special condemnation for Britannia Nicol. She sings the Magnificat nicely, to be sure, but her acting is a mush-mouthed horror made even worse by her floundering failure of a put-on Texas accent. When you’re making a sequel to the one British horror movie with fit and finish comparable to the A-budget Hollywood spookshows of the post-Exorcist era, it really does behoove you to pay attention to such things.

Ah— but maybe The Wicker Tree isn’t really a sequel to The Wicker Man at all, right? I mean, it never calls Lee’s character (or McTavish’s either) “Lord Summerisle,” and it seems vaguely to imply that Tressock is someplace on the Scottish mainland instead of out in the Hebrides or wherever. Also, the pagan observances we see here bear little resemblance to those practiced on Summerisle 40 years before. Hardy’s determination to ride The Wicker Man’s coattails without committing to any specific connection between this story and that one wreaks just as much havoc on The Wicker Tree as Ridley Scott’s equivalent indecision about Alien wrought on Prometheus. The most promising element of this movie is Sir Lachlan’s shabbily dishonest attitude toward his people’s pagan traditions, but Hardy can’t really engage with that unless he’s prepared to offer a straight answer to the question of sequel or retread. If Sir Lachlan really is the fourth Lord Summerisle, then he isn’t just a murderous, conniving asshole— he’d also be the evil antithesis of his great-grandfather, who espoused a religion he never believed in for the sake of downtrodden people whose lives he sought to improve. There’s genuine resonance to that, but Hardy doesn’t seem interested in pursuing it. Nor does he seem interested in the equally important question of how the people of Tressock came to be pagans. The picture painted by the film changes rather drastically depending on whether Tressock represents a long-forgotten survival of pre-Christian culture, or the result of an eccentric modern experiment in social engineering. To tell a story is to create a world. If you can’t commit to that world, then you can’t commit to the story either.

And that brings me to the really galling thing about The Wicker Tree, that it trips over and then ignores a quite serviceable premise for a Wicker Man sequel before proceeding to screw every pooch in the Scottish Lowlands. Remember that The Wicker Man finally resolves itself into a clash of sincerely held faiths. The Wicker Tree, however, depicts a clash of grifts in which the sincerely faithful are merely pawns. It shows Christianity and paganism alike hollowed out by power and greed, and thrown into an opposition that the leadership on neither side actually cares about, except insofar as they can turn a personal profit on it. Beth Boothby has zero qualifications for missionary work (and the techniques she’s been taught are tailor-made for failure anyway), but she gets the gig nonetheless because her pastor knows how good it’ll make him look in the eyes of those who write donation checks to his church. Sir Lachlan doesn’t believe for a second that the American kids’ sacrifice will restore Tressock’s fertility (Steve’s untainted gonads are another matter, of course), but the longer he can fob off the problem as the ire of the gods, the longer he can keep his tenants from having the groundwater tested for radioactive contamination. The Robin Hardy of 1973 could have turned that premise into something clever and powerful and engagingly sad. The Robin Hardy of 2011 seems not to have even understood what he had in his hands.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact