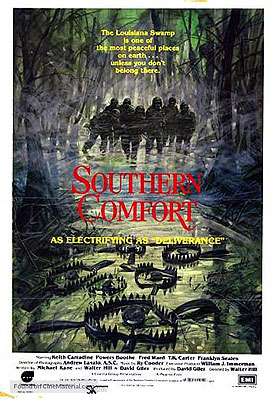

Southern Comfort (1981) ***˝

Southern Comfort (1981) ***˝

I frankly don’t know what to make of director-cowriter Walter Hill’s contention, steadfastly maintained over some 40 years, that Southern Comfort is not and was never intended to be a Vietnam allegory. It isn’t just that so many of the other people involved in this film’s creation have been like, “Yeah, that movie’s totally about ’Nam,” either, although that certainly does factor into my puzzlement. The bigger, more important point is that I can’t see how a person would even come up with this story if they weren’t already thinking about the Vietnam War. Granted, you could get halfway here just by trying to rip off Deliverance or The Hills Have Eyes or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, insofar as Southern Comfort has the heart of a backwoods horror film beating underneath all its action movie gunplay and New Hollywood rumination over the pitfalls of modern masculinity. But the crucial conceits that the endangered interlopers from the orderly world of cities and suburbs are a squad of National Guard troops on a training maneuver gone bad, and that it goes bad in the first place due to the soldiers’ fundamental disrespect for the locals, whom they neither understand nor regard as fully human? Come on. I don’t want to call Hill a liar here, but if he hasn’t been lying about how he understood Southern Comfort all these years, then the film represents a truly amazing eruption of the subconscious.

For this movie’s premise to make much sense, you have to understand that the National Guard isn’t like the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps. Rank-and-file guardsmen don’t live on base, nor are they professional soldiers in any ordinary sense. Indeed, unless and until they get called up for active duty, the life of a guardsman is pretty hard to distinguish from that of a civilian— most of the time. But for a few days out of every month, National Guard personnel are required to report to their local Army base for training exercises, so as to make sure they remember how to march, how to shoot, how to take orders, and how to function as part of a cohesive military unit. The protagonists of Southern Comfort belong to the Louisiana National Guard— although one of them, Corporal Hardin (Powers Boothe, of Mutant Species), just transferred over from Texas— and the end of the opening credits finds them all forming up into a squad under the command of Staff Sergeant Crawford Poole (Peter Coyote, from Return of the Living Dead: Rave to the Grave and Sphere) for their monthly refresher course in bearing arms.

The objective of the weekend’s exercise sounds simple enough. Poole and the seven men of his Bravo Team are to trek across the bayou to the north of the base, to rendezvous the following morning with another, larger unit. It’s what passes for winter in Louisiana, so slogging through the swamp and sleeping in the open are going to be fairly miserable experiences, but inurement to that sort of discomfort is an important part of soldiering, too. The real problem here is that Poole’s map of the area is badly out of date. In addition to all the shallow pools of stagnant water that can be forded without undue difficulty by people who aren’t afraid of a few leeches, the bayou is crisscrossed by a number of sluggish streams deeper than a man is tall, and too wide to be easily swum under the burden of military kit. Some of those streams have changed their courses substantially since the last time anyone came along to document them, and the guardsmen soon find their path quite effectively barred by one. Luckily, Poole’s squad reaches the stream just a few yards down the bank from the campsite of some Cajuns who have clearly had a pretty successful morning of hunting and fishing. What’s more, the hunters’ equipment includes a whole flotilla of pirogues, canoe-like boats optimized for bayou conditions. The Cajuns aren’t around at the moment, but it doesn’t take much argument to convince Poole than he and his men would be within their rights to requisition the pirogues temporarily. Poole orders Corporal “Coach” Bowden (Alan Autry, of Nomads and World Gone Wild, acting under the name “Carlos Brown”) to write a note explaining what they’ve done, after which the troops pile awkwardly into three of the four little boats and shove off.

Nobody ever sees Bowden’s note, though, even leaving aside considerations like the probable lifespan of paper left outdoors in a swamp or the chance of Bayou-dwelling Cajuns speaking any language other than Creole French. The hunters (led by Sonny Landham, of Predator and The Love Bus) happen to return just in time to catch what they see only as a mob of heavily armed men (one of the soldiers, a private called Stuckey [Lewis Smith, from Badlands 2005 and The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai: Across the 8th Dimension], is toting a fucking M60!) making off with most of their boats, and the whole situation goes permanently and catastrophically awry. Because this is a training exercise in an area where contact with civilians is to be halfway expected, Poole and his men have been issued only blanks for their rifles, and even for Stuckey’s machine gun. The only live ammunition any of them has is a single magazine of 5.56mm cartridges that Corporal Lonnie Reese (Fred Ward, from Cast a Deadly Spell and Tremors) smuggled into his kit in the hope of getting in a little recreational poaching on the way to the rendezvous point. The Cajuns have no way of knowing that, however, so when Stuckey, incorrigible prankster that he is, opens fire on them with that goddamned cannon of his, the hunters reply with a fusillade of real bullets. The very first shot takes Poole’s brain clean out of his skull, after which the other men abandon the pirogues and swim the rest of the way to the far shore in order to present more and smaller targets. Alas, in doing so, they lose their radio, their compass, and their map (for all the good the latter had been doing them anyway).

Surprisingly, the Cajuns do not immediately give chase, affording Poole’s second-in-command, Sergeant Casper (Les Lannom), a chance to reestablish some semblance of order and discipline by the time it becomes necessary for the squad to bed down for the night. As the following day progresses, however, it becomes increasingly obvious that Casper isn’t fit to lead a circle jerk, let alone a military unit. For one thing, the sergeant’s grasp of woodcraft would get him kicked out of the Webelos, and it doesn’t take long for Harbin and Private First Class Spencer (Keith Carradine, of Idaho Transfer and Hex)— the two squad-members most likely to find their asses with both hands in a darkened room— to suspect that Casper has them marching around in circles. Meanwhile, the very lack of further engagement with the Cajuns puts the men increasingly on edge, so that most of them are positively spoiling for a fight by the time they come upon the creekside cabin of a one-armed trapper (Bryon James, from Enemy Mine and The Fifth Element), who may or may not be affiliated with the hunters they tangled with yesterday. What Casper intends to be a carefully coordinated encirclement operation devolves almost at once into a disorderly free-for-all, but does at least end with the trapper in custody and the contents of his cabin (including food, ammunition, additional weapons, and even a case or two of dynamite) available for requisition. Bowden, however, picks that moment to go even further off the chain than he had been at the start of the raid. He paints a humongous cross on his chest, makes himself a Molotov cocktail out of a handy mason jar, and lobs it into the depths of the cabin, heedless of the aforementioned explosives. Everything the soldiers might have gained from looting the trapper’s home goes up in smoke, taking with it any inclination the trapper himself might have had to cooperate with his captors in any way.

The guardsmen’s day gets steadily worse from there. Casper continues to lead them everywhere but to the interstate highway which became their nominal destination as soon as it became clear that their original objective was no longer attainable. They come under attack by a pack of huge and savage dogs that might be feral, but could equally well belong to their largely unseen adversaries. And then they start running afoul of booby traps as ingeniously deadly as anything the Viet Cong ever planted in the jungles of Indochina. When Cribbs (The Thing’s T.K. Carter) falls victim to one of those, it might be even more demoralizing than Poole getting shot. The crackup, when it comes, takes a variety of forms. Casper withdraws ever more irrelevantly into the formalism of military procedure. Stuckey and Simms (Franklyn Seales) teeter constantly on the brink of total panic. And Bowden and Reese just go bull-goose loony, the former descending into catatonia, and the latter into violent psychosis. That leaves few options for survival except a mutiny led by either Harbin or Spencer. Neither man really wants the job, but they’re both sharp enough to recognize that somebody has to take charge here. And since those hunters are just about ready to stop toying with their prey at last, the two remaining fully functional members of Bravo Team had better do it soon.

I want to draw your attention now to two things, both of which argue strongly against Hill’s denials that Southern Comfort has anything to do with the Vietnam War. The first is the scene-setting caption that appears onscreen shortly after the end of the opening credits: “Louisiana, 1973.” The winter of 1973 saw the winding down of American intervention in Vietnam’s 20-year civil war, with the last US combat forces leaving the country on March 29th. The conflict would continue to rage among the people who actually had to live with the outcome for a further 25 months, and various sorts of American advisors to the South Vietnamese government remained in place until the very end, but 1973 therefore serves well enough as a touchstone for our inglorious homecoming from Indochina. The second point concerns the significance of the National Guard during the nine years or so when the United States was seriously at war in Southeast Asia. Because guardsmen could just about count on not getting sent to a warzone overseas, volunteering for that branch of the service could be an attractive alternative to taking one’s chances with conscription. Joining the National Guard consequently became sort of a legal and socially accepted form of draft-dodging, especially for guys who felt themselves under pressure to enlist somewhere from relatives or mentors with military backgrounds. Put the two together in a story like this one, and it seems like a pretty straightforward case of the war coming home to engulf those who thought they had avoided it, right? This is the point at which my eyes slide over to Michael Kane and David Giler, the other two writers who contributed to Southern Comfort’s script. Maybe it was one of those guys who had ’Nam on the brain, and Hill somehow just never caught on? If that’s the case, then my money’s probably on Giler. After all, the next time he and Hill teamed up on a writing project, the result was the treatment from which James Cameron developed his screenplay for Aliens, the ultimate 1980’s “when is a ’Nam movie not a ’Nam movie?” flick.

But regardless of what it does or does not “mean,” Southern Comfort unquestionably represents an unusual and unusually effective combination of action movie and backwoods horror elements. Perversely, its secret weapon in both modes is the reduction of the Cajun hunters to an imagined offscreen presence throughout the great bulk of the film. You’ve no doubt heard the adage, first set down in print during World War I, but surely much older even than that, which has it that war is best characterized as long periods of tedium punctuated by moments of sheer terror. That exactly describes what the Cajun hunters put Bravo Team through here, and you can see it eroding the men’s nerves with each jump forward in time. Meanwhile, Hill thoughtfully examines whether, why, and how each individual cracks under the strain, although he commendably never offers anything as crass as a clear answer to those questions. It is interesting, however, that the guardsmen who display the most resilience are the ones least invested in the culture and mystique of the military, and who seem to have little or no sense of themselves as macho men. In some ways, Southern Comfort is a bit like a high-stakes ancestor of Stand by Me, since both movies, whatever the surface-level business of their plots, devote most of their running time to a bunch of guys coming to terms with themselves to varying degrees of success. It’s just that the Cajun hunters are a lot more formidable than Ace Merrill, and the men of Bravo Team know from the outset that they’re being pursued.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact