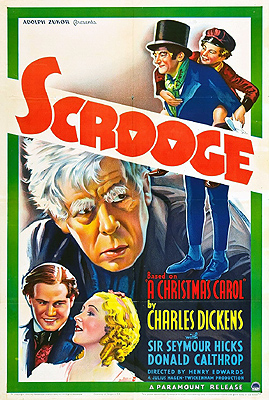

Scrooge (1935) **½

Scrooge (1935) **½

Seymour Hicks first played Ebenezer Scrooge onstage in 1901, and no actor had a stronger link to the part in the eyes of the British public during the early decades of the 20th century. He was therefore the natural choice to assay the role on film in 1913, when Old Scrooge, the first feature-length movie version of A Christmas Carol, was produced. And since Hicks was still at it two decades later, he was even more the natural choice to play Scrooge in the character’s feature-length talkie debut. The 1935 Scrooge gave Hicks a much fairer showcase for his interpretation of Victorian literature’s most famous miser than the silent version had, for a variety of reasons. For starters, after 34 years and roughly 1000 performances, Hicks had at last grown well and truly into the part, no longer having to fake Scrooge’s age. The art of cinema acting had matured as well in that time, and Hicks, to his credit, had kept abreast of those developments, even if the stage remained his natural habitat. And most importantly, Hicks would be able to speak this time. There was another significant change, though, that present-day viewers of Scrooge will most likely not notice at all, but which looms large for me in juxtaposition against the two earlier Christmas Carol movies that I watched for this update. The 1935 Scrooge goes back to Charles Dickens’s original novella to haunt its nasty protagonist with the full quota of Christmas ghosts.

It’s bitterly cold in the counting house of Scrooge & Marley this Christmas Eve, but Bob Cratchit the clerk (Donald Calthrop, from The Clairvoyant and The Phantom Light) can’t just walk over to the fireplace like an adult, with dignity and self-respect, to put some more coal on the grate. That’s because his boss is Ebenezer Scrooge (Hicks, as we’ve already established), a skinflint so flinty that he begrudged the expense of removing his deceased partner’s name from the sign by the front door after Jacob Marley died exactly seven years ago. And indeed when Cratchit resorts to guile and stealth to get a proper flame burning again, Scrooge pointedly reminds him of the wife and six kids that he’s supporting on his 15-shilling-a-week salary. It wouldn’t do, now would it, to get Scrooge mentally adding an increase in the office heating budget to the cost of keeping Cratchit on staff as his assistant? Nor is the clerk the only one to feel the chill of Scrooge’s ungenerosity this evening. When a pair of charity spokesmen (Charles Carson, of The Shadow and Things to Come, and Hubert Harben, who also crossed paths with Seymour Hicks in The Secret of the Loch) come around, they leave both empty-handed and with ears stinging from an angry tirade on the desirability of decreasing the surplus population. Scrooge’s nephew, Fred (Robert Cochran, from The Man Who Could Work Miracles), fares no better when he drops in to invite Uncle Ebenezer to Christmas dinner with him, his wife (Eve Gray, of Murder at the Baskervilles and The Lodger), and their friends. And when a pack of children arrive at the door caroling for alms, Scrooge actually chases them away with a stick! Scrooge does at least grant Cratchit a paid holiday tomorrow, but he bitches up a storm about the supposed injustice of it all while he’s at it.

Scrooge has an unexpected visitor at home that night. No sooner has he gone to bed than his doorbell starts frantically, insistently ringing, but there’s no sign of anyone on the stoop when he peers out the window to see who on Earth could be intruding upon him at this hour, and on this of all nights. Then when Ebenezer returns to his room, he hears the bolt on the front door being forcefully unlatched, the door slamming first open and then shut again, and finally someone dragging some large, heavy object through the house in his direction. Again, though, there’s no one to be seen, even once the door to Scrooge’s bedroom is thrust open from the outside— or at least no one to be seen by us. Scrooge’s uninvited guest is the ghost of Jacob Marley, and the old man can evidently see him just fine. (This off-kilter treatment of the specter is both a harbinger for how Scrooge is going to handle most of its supernatural personages and a bit of a joke on the filmmakers’ part. Marley’s voice is provided by Claude Rains, who had not only tried his hand at Dickens once before, in The Mystery of Edwin Drood, but had recently caused an international sensation being heard but not seen in The Invisible Man.) Marley, every bit Scrooge’s equal for motherfuckery in life, explains that he is now damned to witness forever all the love, joy, and compassion that he refused to share when he had the chance. It’ll be the same for Scrooge, too, if he doesn’t change his ways, and since the two men were friends of a sort, Marley has taken it upon himself on this seventh anniversary of his demise to stage an intervention. Each hour starting at midnight, Ebenezer will be visited by another spirit considerably more ancient and powerful than the mere ghost who set the whole thing in motion. And if Scrooge takes their instruction to heart, he might avoid the restless fate of his late partner.

Spirit #1 is that of Christmas Past, which appears as a featureless blur of light in approximately humanoid form. This entity shows Scrooge visions of things that happened on other 25ths of December, so that the miser might be reminded how he came to be as he is now. For instance, here’s the Christmas when Scrooge’s fiancée— yes, he used to have one of those!— caught him remorselessly foreclosing on a loan to a young couple for whom such proceedings would mean instant and irreversible destitution. Belle (Mary Glynne) had heard rumors of her Ebenezer’s on-the-job character, but that was the first time she’d seen with her own the cruelty that he called “business.” She broke off their engagement on the spot, and Scrooge has never known the love of another woman since. Or how about the Christmas seven years ago, when Scrooge went to work as usual even as Marley lay dying? Scrooge remembers that, of course, but perhaps he’d like to see what bountiful happiness Belle had won for herself by then, precisely by refusing to have anything more to do with a certain basalt-hearted moneylender?

The Spirit of Christmas Present (Oscar Asche) has more narrowly focused plans for Scrooge, taking him on an astral tour of London and its environs to demonstrate how everyone but him is rejoicing tonight, however little reason they may seem to have for doing so. Nephew Fred seems to blow all his money on various sorts of pleasure (both his own and that of people whose company he values), so it’s no surprise to see his house filled with laughter and cheer. But those lonely old lighthouse keepers and those storm-tossed sailors are no less glad despite their circumstances, and even the desperately poor Cratchit household is downright bursting with merriment. Hell, the youngest Cratchit kid, a tubercular cripple called Tiny Tim (Philip Frost), is the happiest of the whole fucking lot, and the only acknowledgement of the family’s dire straits comes when Mrs. Cratchit (Barbara Everest, from The Phantom of the Opera and These Are the Damned) objects to her husband going full bootlicker by proposing a toast to the health of Ebenezer Scrooge.

That last discordant note brings us to the visions proffered by the Spirit of Christmas Yet to Come. (Incredibly, C.V. France got screen credit for the part, even though he never speaks, and we never see more of him than the shadow of his hand!) True, the people whom this spirit shows Scrooge are happy on some possible future Christmas, but it seems like most of them are happy because some universally hated scoundrel has done the world a good turn by dying at long last. Rich men who dealt with him professionally, common folk who had the misfortune to be his neighbors, his own household servants, and even the goddamned undertaker are ecstatic to be rid of the guy, and those in a position to do so are robbing his house and fencing his shit as if it were nothing more than what they were owed by a providence that would allow such a man to have existed in the first place. Scrooge initially imagines the lesson to be that the dead man was a business bastard much like himself, but I think we all know that the situation is in fact a great deal more personal for him than that. And when the spirit takes Scrooge to see what’s happening at the Cratchit house this year, even Ebenezer himself will be hard pressed to deny that he had it coming.

There are a lot of silent versions of A Christmas Carol that I have yet to see, so it may well be that Scrooge is less innovative in this regard than it seems to me at the moment, but what stands out most in comparison to the two of its predecessors that I’ve covered so far is director Henry Edwards’s recognition that this a horror story in form, even if it isn’t really one of those in intent. Ebenezer Scrooge mends his ways because he is terrorized into doing so, and the ideal version of A Christmas Carol would leave the audience wondering, if only subconsciously, whether they’d really have so much easier a time of it if the three spirits were to drop in on them, too, some Christmas Eve. Scrooge is commendably a moody, shadowy picture, whose foggy London street sets could as plausibly be home to Jack the Ripper as they are to Tiny Tim. The band of Cockney gargoyles shown divvying up Scrooge’s possessions in the Christmas Yet to Come segment could have slouched straight out of a Burke and Hare picture. And from the moment Scrooge arrives at home, the film puts its whole back into conveying the unearthly nature of all four apparitions. Mind you, Edwards made some questionable choices in that direction. Jacob Marley would be more effective if we had something to look at, and there’s a moment at the end of his scene that is rendered totally incomprehensible by the conceit that Scrooge has been permitted to see the shades of the damned, but we have not. The Spirit of Christmas Past is too minor a presence for its potentially unsettling portrayal to have the impact that it might. Christmas Present is much diminished without his daemonic sidekicks, Ignorance and Want. And Yet to Come, portrayed as nothing but an impenetrable, amorphous shadow that sometimes resolves itself into an accusatory pointing finger, is an idea lamentably in advance of what special effects could render effectively in 1935.

What’s interesting, though, is that Edwards seems to have arrived at all those depictions not merely by considering what would look good, or what was being done on the stage at the time, but by following Dickens’s own philosophical thinking through to some visual conclusion or other. Notice, for example, that Present is the only one of the Christmas spirits who can be seen clearly and even touched. The past, after all, really is irresolvably blurred by our unreliable memories, while the future really is visible only in the form of shadows cast by things happening now. And of course neither one is at all tangible. Meanwhile, Marley’s punishment, which he is able to expound on more clearly than was possible in any of the silent film versions, comes into focus here as a sly inversion of what the Anglican churchman Frederic Farrar dubbed the Abominable Fancy— that one of Heaven’s principal pleasures would be the opportunity to observe the sufferings of the damned in Hell. It makes good sense, then, that we the living can’t see him, even as he can see us.

I’ve already talked a bit about how Seymour Hicks made the most of this chance to take a mulligan on Old Scrooge, but the observation bears repeating. I still wouldn’t take him over Alastair Sim or George C. Scott, but he’s miles better this time around than, say, Albert Finney. Part of it, naturally, is that Hicks really was old by this point, and a bigger part still is that he got to use his voice, but I’m not sure either one of those factors (or even both of them together) can fully account for how much more believable as a character this rendition of Scrooge feels. And crucially, Henry Edwards seems to have caught on that the hardest part of the story to swallow is the intensity of Scrooge’s sudden turnaround. Not that he or Hicks tone it down any; rather, Edwards openly acknowledges the implausibility of the situation by having everyone who encounters Scrooge in the immediate wake of his epiphany treat him like he’s lost his fucking mind. A Christmas Carol isn’t exactly a tale renowned for its comedy, but it’s genuinely funny watching Scrooge’s surly chambermaid (Athene Seyler, from Curse of the Demon and The Queen of Spades)— one of the servants destined to loot his deathbed had he gone to it unreformed!— humor this baffling good mood of her normally even more ill-tempered master’s, simply because it means she can get something out of him for once.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact