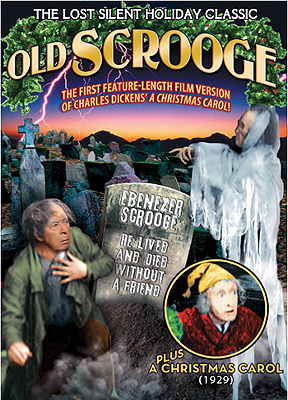

Old Scrooge/Scrooge (1913/1914) **

Old Scrooge/Scrooge (1913/1914) **

It made sense, in 1901, for Walter R. Booth’s Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost to dispense with the Ghosts of Christmas Past, Present, and Future, reassigning all their duties to the damned shade of Jacob Marley. After all, Booth had just six minutes in which to tell the story, so obviously he’d want to streamline it in every way possible. But what on Earth was Leedham Bantock’s justification for doing the same thing a dozen years later, in the first film version of A Christmas Carol to adapt the tale at something like feature length? The reason, rather surprisingly, is that it hadn’t been efficiency alone that caused Booth to cut back on the number of ghosts. Rather than adapting Charles Dickens directly, Booth and Bantock alike were working from J.C. Buckstone’s Scrooge, a perennially popular stage play that similarly laid the entire burden of the titular miser’s reformation and redemption on the specter of his one true friend. Bantock’s Old Scrooge is doubly indebted to the West End version, too, because it stars Seymour Hicks, the actor who’d been playing Ebenezer Scrooge onstage for most of the play’s commercial lifespan, and would continue to do so for much of his own. It was a tremendous casting coup, and the mere fact of Hicks’s presence in the role might go some way toward explaining why Old Scrooge is so much less technically and visually ambitious than Booth’s interpretation. Who needs groundbreaking cinematic storytelling tricks when you’ve got a no-fucking-around star to draw in the punters?

Ebenezer Scrooge (Hicks, whose other film roles include The Secret of the Loch and A Prehistoric Love Story) is a son of a bitch. Just ask the intertitles:

A squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner. Hard and sharp as flint. The cold within him freezes his old features, nips his pointed nose, stiffens his gait; makes his eyes red and his lips blue. No warmth can warm, nor wintry weather chill him. No wind that blows is bitterer than he. He carries his own low temperature always about with him, and does not thaw one degree at Christmas— and this is the day before Christmas. |

Subsequent action demonstrates the truth of every word, too, in case you were worried about Bantock repeating the earlier adaptors’ most damaging mistake. First we’re shown an altercation on the street between Scrooge and a pack of neighborhood children. Next, another intertitle calls attention to the sign outside Ebenezer’s place of business: Scrooge & Marley. The old cheapskate has never had it changed in all the seven years since the death of is former partner! Then comes a callous harangue out the office window directed at Scrooge’s clerk, Bob Cratchit, for dallying too long on the doorstep to say goodbye to his sickly and half-crippled son, Tiny Tim. (I could find no source to match any of the actors in Old Scrooge to their characters, apart from Seymour Hicks as Ebenezer Scrooge. Fortunately, however, all the men in this movie have extremely distinctive noses. I’m therefore fairly confident in identifying Cratchit as none other than J.C. Buckstone, the writer of the source play. No idea about Tiny Tim, though.) Scrooge shows off his Grandmaster-level skinflintery once again by forbidding Cratchit to stoke up the fire in the office hearth— coal costs money, you know! And finally, a veritable parade of visitors gives Scrooge occasion to vent his spleen against the Christmas Spirit specifically. He rejects an invitation from his spendthrift nephew, Fred (I think this might be Osborne Adair), to join him and his family for dinner the following day, and sends the young man packing in the rudest possible manner. He turns away a beggar girl (not a clue— unlike Old Scrooge’s men, most of the women here look pretty much alike) who comes around seeking alms, and works himself up to the verge of apoplexy when Cratchit gives her a few coins out of his own shallow pocket. And when a gentleman social reformer (a director cameo from Leedham Bantock, who can also be seen in front of the camera in Walter Booth’s Santa Claus) drops in to panhandle on a wholesale basis, he gets nothing from the rotten old bastard but a screed about how his tax money already underwrites the prisons and workhouses that are all the poor rightly deserve on a respectable businessman’s account. Frankly, it’s a marvel that Scrooge does no worse than to grumble a bit about the unfairness of having to pay someone not to work when the subject of Cratchit taking Christmas off tomorrow comes up.

Scrooge never goes home on Christmas Eve. I mean, it isn’t as though anyone’s waiting for him there, right? Like, forget marriage or parenthood— can you even imagine this prick taking on the responsibility of keeping a parakeet or a guinea pig? Instead, he nods off in his none-too-easy-looking easy chair in front of the office fireplace while counting and re-counting his beloved money. It is therefore just barely possible to write off what’s about to happen as a dream conjured up by the last blackened cinders of the miser’s burned-out conscience, if you’re the kind of person to whom the makers of 1920’s haunted-house movies thought they were catering by always insisting on a “rational” explanation for everything. Be that as it may, Scrooge hasn’t slept for very long before he is disturbed by the arrival of a hulking, mummy-faced phantom clad in a winding sheet, who claims to be the spirit of the aforementioned Jacob Marley. (The combination of ghost makeup and multiple-exposure transparency makes this ID challenging in the extreme, but my best guess is that the apparition is Leonard Calvert.) Marley, no less pettily evil than Scrooge in life, says that he is now condemned to roam the Earth for eternity, observing others as they enjoy the mutual goodwill and affection that he was too cold and cruel to appreciate when he had the chance. The experience has softened him enough that he now hopes to save Ebenezer from sharing his fate.

Marley begins by conjuring up visions of two long-ago Christmases that helped turn Scrooge into the man he is today, one from his lonely and nigh-loveless childhood, and another from his days as a singleminded young go-getter in the business world. Then he shares with Ebenezer the benefits of his own undead clairvoyance, allowing him to eavesdrop from afar on the homes of Fred and Bob Cratchit, both currently filled with the sort of mirth and generosity that Scrooge has taught himself to reject, having never received it when it was still wanted. And if that study in contrasts fails to impart the lesson, then Marley is equipped to show Scrooge the future toward which he’s been heedlessly barreling: another Christmas not too many years distant, when the miser lies unmourned in a neglected grave while the Cratchits curse his memory for inflicting on them the poverty that has finally claimed the fragile life of Tiny Tim.

It’s remarkable, comparing the two film versions of Buckstone’s Scrooge, how much more primitively static and stagebound Old Scrooge is than a one-reeler from 1901. Whereas Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost skipped around in the modern manner among a variety of locales (even if all of them were manifestly constructed from painted stage flats), Old Scrooge confines itself for the great bulk of its duration to the office of Scrooge & Marley— and while it’s there, the camera remains rooted to a single spot, except on one occasion when a cut to intertitle covers a shift two steps to the right for a better line of sight on Marley’s entrance. What’s more, Bantock never attempts anything comparable to Walter Booth’s door-knocker sequence. The earlier film was stagy in ways that were innovative and exciting in the context of its day, but this one is stagy strictly in the current, derogatory sense.

On the other hand, I must concede that the ghost in this version is an improvement over Booth’s in every way that doesn’t concern manifesting himself out of inanimate objects. Leonard Calvert (if indeed that’s who it is) towers over Seymour Hicks, his rigor mortis-stiff posture contrasting starkly with the smaller man’s histrionic cringing. The ghost’s appearance is impressively unnatural in other ways, too, by the standards of 1913. The hollows of Calvert’s face have been blackened to suggest the shriveling desiccation of the grave, and his costume is no conventionalized white sheet, but rather an instantly recognizable burial shroud. Even the degree of the apparition’s transparency is more controlled and consistent, although Bantock occasionally spoils the effect by moving Hicks through the middle of it, creating distracting anomalies of apparent depth. It would be important that this specter present a fearsome aspect even in a substantially straighter rendition of A Christmas Carol than this one, since it’s the one that’s supposed to scare Scrooge into minding the state of his soul. But it’s absolutely vital here, since Buckstone’s alterations to the story require Marley to assume as well the duties of the terrifying Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come.

Hicks’s portrayal of Ebenezer Scrooge is uneven, but its weaknesses are mostly forgivable coming all the way from 1913. Having played the part onstage for twelve years, Hicks can hardly be faulted for just doing his familiar shtick yet again. After all, he was hardly alone at the time in failing to recognize that playing to the cheap seats is exactly what one shouldn’t do when acting for the camera, or in underestimating how much his performance would be handicapped by the lack of audible dialogue. Similarly, I’m sure that no one who saw Scrooge onstage during its first decade and change in production ever noticed that Hicks was really too young for the part. And in fact it’s surprising how little the star’s relative youth (he was 42 in 1913) impairs Old Scrooge in and of itself. All those years of playing a man some decades his senior obviously served Hicks well when the time came to do it for posterity. Alas, Hicks is much less able at selling Scrooge’s spiritual transformation over the course of this Christmas Eve. That process is driven by introspection forced on the miser by Marley’s intervention, and nothing intro- could survive contact with the wild physical flailing that Hicks uses here to convey every sort of emotion. Fear? Wild physical flailing. Regret? Wild physical flailing. Longing? Sorrow? Remorse? Joyous relief? More wild physical flailing for one and all. The sole quasi-exception concerns self-righteous indignation, which Hicks represents by suppressing his urge to wild physical flailing so strenuously that his whole body shakes with the effort of containing it. This style of acting can do no favors whatsoever for a figure like Ebenezer Scrooge, who was skating along the precipice of caricature to begin with.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact