Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost (1901) [unratable]

Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost (1901) [unratable]

A couple years ago, my December update included seasonally appropriate reviews of the first two films produced for the BBC’s “A Ghost Story for Christmas,” The Stalls of Barchester and A Warning to the Curious. This year, I thought I’d revisit the theme by finally covering a straight adaptation of the Queen Mother of Christmas ghost stories, Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. For once, though, I didn’t really feel like going all the way back to the beginning, simply because there were so many silent one- and two-reelers of doubtful modern availability, few of which sounded very promising anyway. I figured I’d go easy on myself, and start with the oldest sound version instead. After all, that would at least be a beginning, right? Well, the joke was on me, as it happened. It turned out that Seymour Hicks, the star of that earliest talkie Scrooge, had already played the part on film once before, so obviously I had to watch both for comparison’s sake. Then once I’d seen Hicks’s older Scrooge— aptly entitled Old Scrooge— and started delving into the reasons for its strangest departure from the source material, I discovered that its actual proximate basis was not Dickens’s novel at all, but a stage play written by J.C. Buckstone, first performed in 1901. That led to the discovery that Buckstone’s play was also the starting point for Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost, the earliest known film adaptation of A Christmas Carol— and the very movie that I had tried to dodge by beginning with the 1935 Scrooge in the first place! So much for jumping the queue, eh?

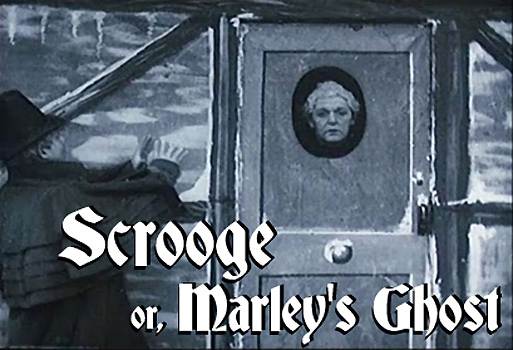

Even when all of it still survived, Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost was an exceedingly short film. It originally ran approximately six minutes, while the sole remaining print, which is missing the concluding redemption sequence and all but the first few seconds of the prophesied death of Tiny Tim, runs just under five. And as that ought to imply, Dickens’s narrative has been compressed here almost beyond recognition. Indeed, Heaven help anyone who comes to this movie unfamiliar with the story, for it is practically devoid of exposition, introductions, or anything else that might enable the viewer to interpret what they’re seeing. I rather suspect that Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost was meant to play with a live narrator filling in the blanks, which was a common practice in France at the time, and may have been in Britain as well. In any case, I was astonished to see nothing onscreen whatsoever to indicate that Ebenezer Scrooge (Daniel Smith, the sole performer whose identity I’ve been able to determine) is a hard-hearted, Christmas-hating miser, let alone that the other fellow whom he’s cheerfully sending home from his office in the opening scene is supposed to be Bob Cratchitt, the clerk whom Scrooge knowingly and maliciously keeps in poverty with his stinginess. And with those two vital pieces of information unavailable, there’s also no internal clue as to why Scrooge is visited in his home that night by a ghost, and precious little to suggest what the ghost is driving at by showing him visions of his youthful interactions with unidentified girls, the Christmas Eve festivities at the homes of the Cratchitt family and someone named Fred, and a gravestone bearing his own name. It’s mostly on us (unless, again, Scrooge was supposed to have live narration) to do our homework, and to surmise from there that the ghost is Scrooge’s old business partner, Jacob Marley; that the unnamed girls figure at pivotal junctures along Scrooge’s road to assholism; that Fred is Scrooge’s semi-estranged nephew; and that the grave is a warning of the damnation, both social and metaphysical, that awaits Scrooge if he continues on his present path.

But while it may be a nigh-incomprehensible whirlwind of barely-connected highlights from Buckstone’s play, Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost is significant for reasons that go beyond its status as the fumbling first attempt to film A Christmas Carol. This movie was one of several collaborations between two towering figures from the British cinema industry’s primeval era, Robert W. Paul and Walter R. Booth. Paul, who produced this version of Scrooge, was an inventor of scientific instruments who got into the nascent movie business in 1894, when a pair of Greek businessmen hired him to reverse-engineer a copy of the Edison Kinetograph, which had unaccountably not been patented in the UK. He subsequently teamed up with photography pioneer Brit Acre to develop the first 35mm movie camera produced in England, and devised a commercially viable projector as well. By 1896, Paul was working on portable cameras, and had perfected a cranking system that could cycle the film in both directions to facilitate multiple exposures. That innovation led French trick-film maestro Georges Méliès to favor Paul’s cameras early in his career, since multiple exposure was one of the most important special effects techniques of the day. Then in 1898, Paul built the first motion picture studio on British soil, completing the oft-observed transformation from cinema technologist to first-generation movie mogul. Booth, meanwhile, we’ve already met, in the context of his extraordinary sci-fi war movie, The Airship Destroyer.

It was Booth who directed Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost, and his contributions that make it worth watching today despite all the ways in which it doesn’t really work. Like his better-known French counterpart, Méliès, Booth came from the stage, and although one tends to speak pejoratively nowadays of movies that look like they belong there, just the opposite is warranted for films made around the turn of the 20th century. At a time when “motion picture” was often understood literally, as simply a picture that moved, it represented a considerable advance in the state of the cinematic arts to import live-theater conventions like plot and characterization, even when those things were bungled as badly as they are here. Similarly, it was a big deal in 1901 for a film to be organized into multiple distinct scenes, each with its own set dressing and narrative purpose. And although the physical environments of Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost are designed and built to positively childish standards, their crude artificiality has a definite charm to it. The same goes for the double exposures used to make a supernatural presence of the anonymous actor playing Jacob Marley. True, the specter is nothing more than a man draped in a white sheet, but he dominates the proceedings sufficiently to earn his promotion to co-title character. The ghost’s apparent insubstantiality is something that only film could achieve in this era— and that isn’t the only respect in which Booth shows signs of appreciating the unique capabilities of the medium. Unusually for a film of the early 1900’s, Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost makes sparing but noticeable use of the camera’s ability to vary the apparent distance between the audience and the action. Although most of the scenes are framed widely enough to take in the entire set in a single image, Scrooge’s arrival at home is shot at much shorter range to facilitate the movie’s most ambitious and effective trick image— an extremely sophisticated cinematic technique by the standards of 1901. I’m quite certain the sight of Scrooge’s door-knocker transforming into a dead man’s face sent chills up many a spine during this film’s initial release.

In the final assessment, though, none of that is able to overcome a flaw so central and profound that it makes nonsense of the entire film. I’m not sure how to apportion the blame among Robert Paul, Walter Booth, and Daniel Smith himself, but the portrayal of Ebenezer Scrooge here is both inexplicable and inexcusable. Nothing in Scrooge’s actions, demeanor, or even mere physical appearance remotely suggests a rich rat-bastard in need of supernatural intervention on both his own behalf and that of the exploited innocents whom he’s on track to take down with him. Granted that Scrooge, or Marley’s Ghost has no intertitles for dialogue, ruling out any employment of the miser’s famous catchphrase in response to expressions of Christmas cheer or exhortations to generosity, but that’s the least of this Scrooge’s problems. We’re shown no turning away of panhandlers or charity collectors, no rude rebuff of Fred’s holiday well-wishing, no berating of Bob Cratchitt for using too much coal in the office fireplace. We don’t even get a shot of Scrooge feverishly counting coins, which ought to be the bare minimum for setting him up as a penny-pinching materialist. But worst of all, Smith imbues the character with a downright sunny disposition, to the point that his opening interaction with Cratchitt looks more like a fond farewell than the grudging grant of a paid day off. Even live narration could do nothing for this scene but to create cognitive dissonance. It would be one thing, I suppose, if this were a case of strangely misguided revisionism, but it hardly seems to be. Dickens’s familiar plot plays out as expected, except insofar as Jacob Marley has taken on the jobs of all four spirits, and although the final scene is missing, I see no reason to imagine that it ended the film on a surprising note. No, so far as I can tell, we’re still supposed to interpret what happens to Scrooge this Christmas Eve as the reformation of a greedy misanthrope, but that’s hard to do when there’s never been any sign of his greed or misanthropy in the first place.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact