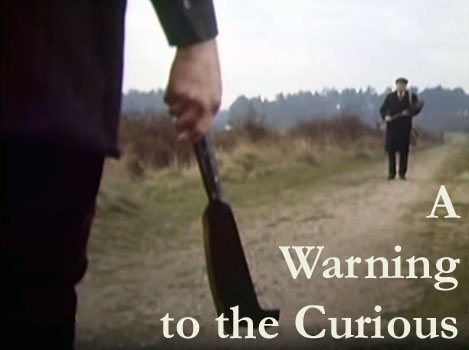

A Warning to the Curious (1972) ***½

A Warning to the Curious (1972) ***½

Somewhat unusually for a writer of his era and genre proclivities, M.R. James never developed any recurring characters around whom to build his tales of strange things uncovered in the archives and annals of old churches and similar places. He had no Professor Challenger, no Carnacki the Ghost-Finder, no John Thunstone appearing in story after story to give his writing a readily marketable brand identity. Probably that was because his primary “market” was the faculty Christmas parties at King’s and Eton Colleges, while the writing of fiction was for him more a hobby than a career. No need to chase the tastes of book or magazine readers when you’re only incidentally writing for publication in the first place. Even so, there’s a pronounced sameness to the usually unnamed narrators whose antiquarian research brings James’s age-old hauntings and such to light. One could argue, then, that writer/director/producer Lawrence Gordon Clark was merely carrying that tendency to its logical conclusion when he brought back The Stalls of Barchester’s Dr. Black for an encore in A Warning to the Curious, his second made-for-TV mini-movie under the “A Ghost Story for Christmas” banner. This time, however, Black would find himself more directly involved in the supernatural goings on, at considerably greater risk to his mousy and fastidious person.

There’s a legend in Norfolk (not a real one in the form presented here, but derived from a real one in much the same way as Lair of the White Worm’s Dampton Worm is rooted in the legend of the Lambton Worm) which has it that one of the rulers of the Viking-beset Dark Ages kingdom of East Anglia sought to supplement the conventional defenses of his realm by burying three enchanted crowns in secret places along the coast. The idea was that so long as at least one of them remained in place, no seaborne invader would be able to set foot on East Anglian soil. The tale goes on to specify that one of those crowns was dug up and melted down by thieves in the Middle Ages, while a second was carried out to sea when coastal erosion overtook its resting place. The third crown remains, however, continuing to cast its protective spell. In the village of Seaburg, the locals contend that it’s somewhere close by— and members of a family called Ager will tell you that they have a special duty to guard its secret. An archeologist (Julian Herington) learns just how seriously the Agers take their supposed obligation when he goes digging for the crown one morning in the fall of 1917. He happens to have picked exactly the right spot, you see, and obviously it wouldn’t do for East Anglia to be left without the crown’s protection while the Great War rages across the North Sea. William Ager (John Kearney), sole representative of his line in the present generation, has been spending all his waking hours standing watch over the last crown’s burial site ever since the Germans marched into Belgium (nevermind his tuberculosis!), and when the archeologist refuses to lay off his excavation, he gets a brush-cutting cleaver in the skull for his intransigence.

Twelve years later, another man— a newly unemployed Londoner by the name of Paxton (Peter Vaughan, from Die, Die, My Darling! and Brazil)— arrives by train in Seaburg with his own designs on the legendary crown. Although he’s had no formal training in the field, Paxton has made a lifelong hobby of archeology, and when he encountered a book on the legend of the Anglia Crowns, it set him fantasizing about how it would be for an amateur like himself to make a find of such magnitude. Then the shockwaves from the American stock market crash took down the London Stock Exchange, too, and Paxton acquired a more practical reason to pursue those fantasies. Given what happened to the last out-of-towner to come round digging where digging wasn’t wanted, it might sound like a stroke of good fortune for Paxton that William Ager succumbed to his illness not long thereafter, and that the whole Ager lineage died with him. This is an M.R. James story, though, so it’s a safe bet that the crown is now guarded by something a great deal more formidable than one consumptive loony with a brush-chopper.

Paxton goes first to the local church, where the vicar (George Benson, from The Creeping Flesh and Old Mother Riley Meets the Vampire) confirms the currency of the Anglia Crowns legend among the people of Seaburg, and tells him about the Ager family’s claim of responsibility for safeguarding the last one. The vicar even shows Paxton William Ager’s grave, and tells him what little he was able to learn about the tightlipped man during the eight years that their respective tenures in Seaburg overlapped. Next, Paxton tries an antique shop in the hope of acquiring an old map of the area, and makes a find beyond his wildest dreams: a family bible that had belonged to William Ager himself! He hits a wall, though, when he asks Arnold, the domestic at the inn (David Cargill, of The Pleasure Girls), for further information on the Agers. Unlike the vicar and the antique dealer (Roger Milner), this bloke is a Seaburger born and raised, and he knows it can mean just one thing when outsiders get curious about that particular family. Arnold pleads totally unconvincing ignorance, leaving Paxton to his own devices. Indeed, as the days of Paxton’s search wear on, Arnold does everything he can to get in the way. Then there’s Dr. Black (Clive Swift again). He likes to spend a week or two in Seaburg every year, vacationing from both his academic responsibilities and his wife. Given the professor’s interests and expertise, he could become either a valuable ally to Paxton or a dangerous rival, so a certain amount of caution is called for in approaching him. Paxton will have plenty of opportunity to sound Black out, however, because they’re both lodging at the same inn. Paxton’s biggest breakthrough comes when he happens to meet the Cockney girl (Gilly Fraser) whose father is now renting what used to be William Ager’s cottage. She’s picked up plenty of gossip in the two years she’s lived in Seaburg, but none of the locals’ reticence about her predecessor in the house. She points Paxton toward the stretch of woods about three quarters of the way to the neighboring town of Thruxton, where Ager was said to have spent most of his time during the final years of his life. Putting that together with what the vicar said before, Paxton realizes that he must have identified the crown’s general hiding place at last.

It’s worth observing, though, that ever since Paxton arrived in Seaburg, he’s been seeing from the corner of his eye a black-clad figure hanging around too far away to hail or to identify reliably, but near enough and persistently enough to convey the distinct impression of keeping watch over the newcomer’s movements. And because we, unlike Paxton, saw the prologue about the doomed archeologist, we, unlike Paxton, are in a position to notice the resemblance that figure bears to William Ager. As is so often the case with ghosts, this one’s powers seem to be circumscribed by rules beyond the ken of mortals, for although it doesn’t intervene to prevent Paxton from locating and digging up the crown, it becomes increasingly menacing once the prize is actually in his hands. Eventually, Paxton becomes so frightened that he resolves to put the crown back where he found it, but by that point, he’s much too scared to face Ager’s ghost alone on its own turf. Dr. Black may not make a very promising Van Helsing, but he’s the best Paxton can get under the circumstances.

A Warning to the Curious is a much more conventional sort of spook story than The Stalls of Barchester, and William Ager’s ghost is downright pedestrian compared to some of the things that haunt M.R. James’s weirder fiction, but this second “Ghost Story for Christmas” is also just a lot scarier than its predecessor. The difference exemplifies what I was saying in my review of the earlier film about urgency. However bad an end Archdeacon Haynes came to, he came to it a long time ago— even from the perspective of characters living a long time ago from the audience’s perspective. The threat posed by William Ager’s ghost, however, is a present reality for the characters in A Warning to the Curious, and the terms of the story are such as to imply that it will continue to be present for anyone else foolish enough to go digging in those woods for the rest of time. Also, although undead creatures standing unending guard over things is a sufficiently commonplace premise, I have to respect the bizarre grisliness of a ghost that hacks people into hamburger with a goddamned cleaver. I mean, not that people tumbling down the stairs to break their necks are any less dead, but cleaver-hacking is on an altogether higher plane of Things You Don’t Want to Happen to You, so far as I’m concerned. It’s doubly unsettling, too, for Ager’s ghost to employ such a brutal modus operandi, considering how insubstantial Clark makes him seem otherwise. We never get to see him really clearly once he returns from the grave, even when he isn’t downright invisible or taking some form other than his own, and that would normally seem like a cue to expect the kind of ghost that can’t directly harm the living.

A Warning to the Curious draws a lot of power from Clark’s depiction of the setting as well. British beaches are forbidding places, where gray sand meets gray sea under a gray sky, and this one in particular seems like a natural habitat for things that are themselves not exactly natural. It’s very much like that bleak, miserable beach in Dieppe that shows up sooner or later in practically every Jean Rollin movie from the 70’s. You can just about feel the chill, damp North Sea wind blowing out of the screen at you, and smell the rotting clumps of marine crud dumped on the sand by the receding tide. And of course British horror movies had been relying on the atmosphere of tiny, remote villages where nobody trusts outsiders for reasons that eventually become incredibly obvious since at least the mid-1950’s. It only stands to reason that they’d be pretty good at it by 1972. It’s an interesting twist, though, that in this sinister little village, the supernatural menace and the locals who cover for it are arguably in the right— at least if you believe that business about the buried crown keeping East Anglia free of invading armies. Honestly, I’m a little bummed that the remainder of the “Ghost Story for Christmas” films are so damned short, because I’d love to have an excuse to talk about them here.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact