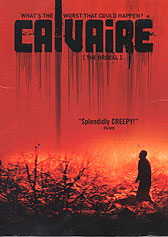

The Ordeal/Calvaire (2004) ***

The Ordeal/Calvaire (2004) ***

Backwoods horror, at least in the sense typified by Deliverance, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, and The Hills Have Eyes, has been since its inception a distinctly— indeed, nearly exclusively— American genre. The rest of the world has backwoods too, however, and the dread of city people for the inhabitants of those backwoods is as old and as universal as civilization itself, so there is really no compelling reason why that situation should continue to stand. Nevertheless, it is perhaps rather odd that one of the filmmakers belatedly drawing backwoods horror out into the big, wide world would be a Belgian arthouse director. Fabrice Du Welz professes to be a longtime fan of such movies, though, and claims he knew all along that his feature debut was going to be a horror picture. Now you probably don’t need me to tell you that a French-speaking director of arty shorts is going to have a slightly different concept of what a horror movie should do and be than would a Tobe Hooper or a Wes Craven, and indeed there are long stretches in which The Ordeal has only its premise to indicate that it is supposed to be a horror film at all. Du Welz does unnervingly weird very well, however, and The Ordeal consistently succeeds at that level, even when that’s really all it’s doing.

Marc Stevens (Laurent Lucas) is what would most likely be called a lounge singer in the United States, but he’s a long way from an opening gig supporting the reanimated corpse of Sammy Davis Jr. at the Luxor. On the night we meet him, for example, he’s performing at a nursing home somewhere in rural Wallonia. Those old ladies don’t give a damn, though— he’s a star so far as they’re concerned. In fact, one of them (Gigi Coursigny) sneaks backstage after the show to make passes at Stevens in his dressing room. A quick aside here for the benefit of any elderly, computer-savvy women who might be both reading this review and contemplating trying to score with 30-ish singers brought in to entertain them at the retirement center: “You should fuck me now, ‘cause I’ll probably be dead by the time you come back this way next year” is not exactly the optimal sales pitch. Also, handing the guy an envelope full of topless polaroids of yourself isn’t much better, even if, like the woman who tries to snag Marc in the midst of his departure, you happen to have been a notorious porn queen in your youth. (The second smitten retiree is played by Brigitte Lehaie, once famous for movies like Education of the Baroness and Night Fever, more recently a radio talk-show hostess, and now a high-ranking member of a center-left French political party.) Marc is very happy to get on the road again, southbound for a Christmas gala gig two days from now.

What? You don’t actually think he’s going to get there, do you? No, of course not. Marc’s van is a ghetto-ass piece of shit (probably even worse than my band’s van), and it breaks down on a winding forest road in what appears to be the dead center of fucking nowhere. The closest thing Marc has so far this evening to luck on his side consists of a rusty little sign he saw nailed to a tree a while back, advertising the presence of a Bartel’s Inn some three kilometers distant. The sign said nothing about the inn’s precise location, and a three-kilometer walk through the woods on a rainy December night would suck a lot, but there doesn’t appear to be but one road through this part of the forest, and a hike of that magnitude is at least doable. Also, no sooner has Marc concluded that spending the night at Bartel’s is the only practical course of action than he has an unexpected encounter with a young man called Boris (Jean-Luc Couchard, from The Teeth of the Night), who is out looking for his missing dog. Boris is a little reluctant to interrupt his search in order to direct Marc to the inn, but he eventually offers to lead him there on the condition that he keep his mouth shut so that Boris will be able to listen for his dog during the detour. Incidentally, just between you and me, I don’t think this kid Boris is playing with a full deck— in fact, I’d be amazed if he had one card higher than about an eight of diamonds. Nevertheless, he steers Marc in the right direction, and there turns out to be plenty of room at the inn. And by a further stroke of good fortune, the eponymous Bartel (Jackie Berroyer) professes to be an accomplished mechanic. He even has a tractor powerful enough to haul Marc’s van off the road.

The thing is, though, that the more time we spend with Bartel, the weirder and less trustworthy he seems. He’s extremely needy, clingy, and moody, and he evidences a much greater emotional investment in Marc’s presence at the inn than is either normal or explicable solely in terms of the establishment’s obviously poor economic performance of late. Bartel has crying jags. He pursues Marc’s company to a degree that neither the stranded traveler nor we in the audience can help but regard as intrusive. He affects a camaraderie with Marc that feels similarly invasive, based on a supposed commonality of background— Marc sings, while Bartel says he used to be a standup comic. Now Bartel also says his wife (a singer herself) deserted him years ago, and we can perhaps cut him a little slack for his odd behavior because of that. Believe me, I know how long that sort of thing can fuck up a man’s life. Still, it does seem a little much. Equally worrisome is Bartel’s secretiveness. He acts like he doesn’t want Marc to see what he’s doing to the van while he works on it the following morning, and when Marc expresses the intention of going out for a walk, Bartel cautions him to stay away from the village. He won’t say why beyond that the men of the village are not “artists like us,” which seems wholly inadequate to explain the urgency of the innkeeper’s warning. And the way Bartel snoops around inside Marc’s van as soon as the latter man heads off down the road into the woods? Now that’s really creepy.

On the other hand, maybe Bartel really does have Marc’s best interests in mind, at least when it comes to the villagers. Marc, true to his word, does not venture into the village per se, but he approaches it closely enough to reach one of the outlying barns. Inside, he spies a group of men led by one about Bartel’s age (Philippe Nahon, from High Tension and Brotherhood of the Wolf); the purpose of their gathering appears to be a rite of passage for the leader’s son (Philippe Grand’Henry). Rites of passage always tend to be off-putting to those outside of the relevant culture, but this kid is fucking a pig, and there’s no way that’s normal, even in the farthest depths of the Walloon back-country. I’d say Marc is wise to keep out of sight and turn back the way he came as quietly as possible.

Of course, that puts him back at the inn with Bartel, and we’re about to see that that’s just as bad. Upon his return, Marc is told that the van requires some parts that Bartel doesn’t have on hand. He’s called for them, he says, but there’s no chance of them being delivered until at least tomorrow. That’s going to make for a tight schedule if Marc is to meet his next singing engagement, but what more can Bartel do? That night over dinner, the innkeeper and his guest have a fateful conversation. The major topic is Bartel’s vanished wife, Gloria, and the years the couple spent together performing as a double act before settling down to open the inn. Bartel tells Marc one of his favorite jokes from his old routine, and insists that Marc reciprocate with one of his love songs. Marc takes some pushing, but he eventually complies, and the older man finds it a moving experience. So moving, in fact, that he determines not to let Marc leave. He smashes and burns the van the next morning, and when Marc tries to intervene, Bartel clouts him on the head and ties him up. It’s very simple, you see. Gloria was a singer; Marc is a singer, too, and his performance last night touched Bartel in much the same way as Gloria’s used to; ergo, Marc must in some sense be Gloria, repenting of her desertion and returning to Bartel at last. Needless to say, Marc is less than thrilled with the prospect of this “reconciliation,” but getting out of it is going to be a rather tall order. He might slip by Bartel eventually, but the innkeeper is pretty tight with Boris (remember him?), and that guy spends just about literally all his time combing the woods for his dog. I’m sure he’ll never find it (if indeed it ever really existed in the first place), but he’ll sure as shit be able to find a handcuffed man with a crusty headwound fleeing through the forest in a bright orange parka and a dress too small for him. As for the villagers, the apparent antagonism between them and Bartel might make them look like potential allies for Marc, but something tells me that if those pig-fuckers ever get wind of the news that Bartel has a captive up at his inn, a rescue mission won’t exactly be the first thing on their minds when they come to see for themselves.

Here’s a little trivia question for you: What do Fabrice Du Welz and Andreas Schnaas have in common? Answer: Their debut features each include a bit during the final act when the protagonist comes across Jesus crucified in the woods for no rationally comprehensible reason. Fortunately, that mysterious lapse of judgement is the only significant point of resemblance between The Ordeal and Violent Shit. Du Welz’s film represents a creditable effort to put a local spin on an imported tradition, and unlike all too many genre movies made by self-conscious auteur directors in recent years (take Shadow of the Vampire as an example), it shows no sign of embarrassment at being what it is. That said, The Ordeal is still a very unconventional horror film, characterized by a great deal of experimentation, especially as regards pacing and characterization. The advance of the story ranges from leisurely to glacial, and while Du Welz makes that work for him, it creates a very different feel from that of this movie’s more familiar American cousins. Another peculiarity of The Ordeal is that Du Welz deliberately made Marc as complete a cipher as possible, giving us no insight whatsoever into his motives or personality. He may be the official viewpoint character, but for the most part, he is an object to which the story happens rather than an active participant in it. In fact, everybody in the film is rather opaque by ordinary standards. We get to know Bartel a little better than the others, but never well enough to venture more than a guess as to the mechanics of his psychosis. Is it really just because he likes the way Marc sings that he decides his unexpected guest is Gloria in a new guise? Or would any outsider who came to the inn do just as well? Hell, for that matter, how often has this sort of thing happened? There are hints— but never more than that— that Marc might not have been the first surrogate Gloria, and indeed you kind of have to wonder if maybe Gloria herself wasn’t really Gloria once you seriously start thinking about it. What it adds up to is that The Ordeal is a movie that makes exactly the right amount of no sense, and that it gives you all the time in the world to ponder its puzzles.

Another thing Fabrice Du Welz isn’t at all embarrassed of is his influences. The Ordeal contains an unusual amount of frank emulation of earlier works by directors whom Du Welz admires, most conspicuously Alfred Hitchcock. The pivotal dinner scene is openly cribbed from Psycho, for example, while the almost total lack of music puts one in mind of The Birds. Most of the time, these nods to Du Welz’s heroes are either unobtrusive enough to fold themselves into the fabric of the movie or (as with a very bizarre scene set in the village, which Du Welz modeled on a sequence in Andre Delvaux’s One Night… a Train) are so thoroughly disorienting as to reinforce the sheer, mad absurdity of Marc’s plight. Unfortunately, however, there are a few instances in which Du Welz picks the wrong tendencies of his idols to copy, the most serious being a long tracking shot during the climax, in which the camera swoops up from a man’s eye-level until it is looking straight down upon the action from above. It’s a textbook piece of Hitchcockian overreach, a marvel of cinematography so arresting that the action of the film at that point pales in comparison, and it comes at absolutely the worst possible time. “Marc Stevens?” I found myself thinking. “Eh— fuck him, who cares? I want to know how you did that!” Up until then, The Ordeal had been a very intimate, very personal sort of nightmare, and very involving even despite the deliberate nullity of its protagonist. It breaks the mood completely when the camera goes swooping up through what certainly ought to be the ceiling of Bartel’s parlor at the story’s dramatic peak, and the movie never quite recovers from the disruption.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact