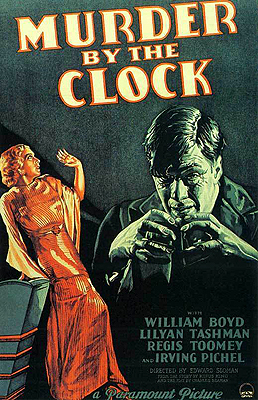

Murder by the Clock (1931) **½

Murder by the Clock (1931) **½

Murder by the Clock is the most important early American horror movie that you’ve probably never heard of. That’s because it was the first major-studio fright film to be made in Hollywood after the dust settled from Dracula, the first attempt by a peer rival to horn in on Universal’s new racket. In this case, the rival was Paramount, which would later produce some of the most effective horror pictures of the 1931-1936 boom years— and that makes Murder by the Clock doubly interesting, because it doesn’t quite manage to be one of those. Although there’s plenty of strong material here, Murder by the Clock is just a bit less than the sum of its parts, hampered by a conservative over-reliance on tropes carried over from the 1920’s.

As she gets on in years, Julia Endicott (Blanche Friderici, of Thirteen Women and The Cat Creeps) increasingly despairs for the future of the Endicott dynasty. Her son, Philip (Irving Pichel, from Return of the Terror and Dracula’s Daughter), has the strength of a giant, but the mind of a cruel and violent child. He can’t even be trusted to look after himself, let alone preserve and foster whatever family empire was bequeathed to Julia by her forebears. She might as well leave everything to Roberts the housekeeper (Haunted Gold’s Martha Mattox, who played the same part as Blanche Friderici in an earlier version of The Cat Creeps, Paul Leni’s The Cat and the Canary) as make Philip her heir. On the other hand, Julia’s nephew, Herbert (Walter McGrail, from Reefer Madness and The Bowery at Midnight), is a drunk and a weakling, totally under the thumb of his devious wife, Laura (Lilyan Tashman, another Cat Creeps alumna). Now if Julia could see beyond her own prejudices, it would be obvious to her that Laura is exactly the person she should want looking after her patrimony. The old bitch herself isn’t half as ruthless, and Laura has the brains, the beauty, and the interpersonal acumen to get away with just about anything. The trouble is, Laura has always been too frank for her mother-in-law’s taste about coveting the family fortune, and as a matter of fact it’s by no means impossible to imagine the girl taking steps to speed her inheritance along, if you know what I mean.

Indeed, when Julia yields at last to the inevitable, and composes her will so as to favor her nephew over her son, Laura almost immediately begins spinning skeins of fancy around her husband’s head regarding how happy they could be if only the old hag would hurry up and die already. Eventually, Herbert takes the hint, sneaks into the Endicott mansion under cover of darkness using the hidden passage linking the house to one of the crypts in the family cemetery out back, and strangles his aunt to death. The method of the crime is calculated to cast suspicion on the newly disinherited Philip, whom everyone knows to possess more than enough power in his massive hands to choke the life from a woman as frail and aged as Julia Endicott. That’s exactly the conclusion to which the chief of police (Frank Sheridan, of One Exciting Night and The Witching Hour) leaps at the coroner’s inquest, and Philip is soon locked up in the municipal jail to await trial.

The one person who doesn’t who doesn’t buy the theory of Philip’s guilt is a detective by the name of Valcour (The Midnight Warning’s William Boyd— not the William Boyd famous for playing Hopalong Cassidy). For one thing, Valcour wonders whether Philip even has the mental capacity to understand a concept like disinheritance. And for another, Valcour sees the halfwit’s titanic grip as an argument against his guilt. The victim’s throat, you see, was barely bruised. Surely a throttling from Philip would have left her with a crushed windpipe, dislocated vertebrae, severed spinal cord, and heaven alone knows what sort of minor soft-tissue damage. The chief tries hard to stop Valcour from pursuing that line of reasoning (evidently in the interest of limiting the Endicott family’s exposure to scandal), but not even a demotion from lieutenant to sergeant is enough to drag this bloodhound off the scent.

It’s a good thing that Valcour is so tenacious, too, because Laura isn’t done yet. For some considerable while now, she’s also been carrying on an affair with Herbert’s best friend, the artist Thomas Hollander (Lester Vail). Hollander is the one she really loves, for whatever value “love” holds in the mind of a psychopath, but Tom is merely rich, whereas the Endicotts are wealthy. (I quote Chris Rock on the difference: “Shaq is rich. The white man who signs Shaq’s checks is wealthy.”) Now that Laura and Herbert are in possession of the Endicott millions, however, there’s no reason why she shouldn’t eliminate her husband and have her preferred man as well. All it takes to turn Tom’s compromised friendship to hate is a cock-and-bull story painting Herbert as a domestic abuser, after which Laura engineers the ideal alibi by inciting Philip to break out of jail. Alas for Laura, Valcour is keeping a close watch over the Endicott place, Chief Dipshit be damned, and the detective is the one man in this picture too upstanding for Laura to buy off with veiled promises of an extraordinary lay.

It isn’t hard to understand everybody’s confusion in February of 1931, when Dracula was not merely the biggest hit of the year so far, but indeed so big a hit that anything else in the pipeline for the next ten months was going to have a hard time topping it. After all, Dracula was a modestly budgeted film with no major stars, and although it was based on a hit play derived from a successful novel, neither source had been a phenomenon on the scale of the movie. Meanwhile, horror pictures had been produced at a modest but steady rate throughout the past decade and a half, yet only the merest handful of them had ever become blockbusters. So what the hell had happened? Were spookshows simply about to have a moment, or was there something special about this one that didn’t immediately meet the professional eye? Murder by the Clock is largely predicated upon the former assumption, whereas the latter was closer to the truth. What made Dracula and most of its Universal successors unique at first was their unrepentant embrace of the fantastic. Count Dracula was a genuine vampire; Henry Frankenstein was a genuine creator of animate corpse collages; no hint of a “rational” explanation ever emerged in their movies to undercut the imagined reality of the impossible.

Against that backdrop, Murder by the Clock looks timid indeed. At heart, it’s just another spooky house mystery, and very few spaces on its genre Bingo card remain unstamped by the time the closing credits are displayed. Hateful old millionaire? Check. Avaricious relatives of same? Check. Mental defective who looks and acts like a killer, written in to deflect attention away from the real culprit? Check. Hero detective, phony ghost (for a somewhat loose definition of “ghost”), and insufferable comic relief couple with ostensibly funny foreign accents? Check, check, and (Christ preserve us!) check. You can’t accuse Paramount of not learning their lesson, however. The studio had Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde ready for launch by New Year’s Eve, and Island of Lost Souls would follow not too much later.

On closer inspection, though, Murder by the Clock is less fusty and antiquated than it initially appears. I haven’t yet mentioned Julia Endicott’s fear of being buried alive, because it doesn’t become relevant to anything until after the point where I intended to break off my synopsis. However, when it does come into play, it gives a welcome dash of Poe flavor to a scene that would otherwise be a lifeless exercise in cliché. Julia’s phobia also contributes to the atmosphere of the mansion, insofar as the alarm system she has rigged up in her cell in the mausoleum— a sort of siren that produces discomfitingly human-like moans and shrieks— is far and away the creepiest thing on the premises. I also like the portrayal of Lieutenant Valcour, which brings in a second set of unexpected influences. Although there’s usually a detective character to be found somewhere in a spooky house movie, only rarely does such a film revolve in this way around a battle of wits between him and a villain whose identity and objectives are known to the audience. The question in Murder by the Clock is not who is behind all the killing, but rather how Valcour is going to trick Laura into the open. From the audience’s point of view, anyway, this is less Bloodhound Anderson trying to catch the Bat, and more Nayland Smith hunting Fu Manchu or Inspector Juve hunting Fantomas.

It’s also a bit like Philippe Guarande battling Irma Vep, which brings me to the foremost reason why you should watch Murder by the Clock in spite of all its stumbles and slips. Although she’s by no means as flashy as a vampire, a werewolf, or a mad scientist, Lilyan Tashman’s Laura Endicott is one hell of a monster. Over the course of this film, she suborns three men into acting as her assassins, plays on the prejudices of a fourth to get a blind eye turned toward her activities, and does her damnedest to manipulate a fifth into letting her get away with everything. She combines the glitz and glamour of the silent era’s “vamp” style of femme fatale with a startling foretaste of the crueler, grittier, and more hands-on style that would emerge once film noir began to coalesce firmly in the mid-1940’s. And through it all, we’re encouraged to see her as a feminine reinvention of the diabolical mastermind— a profession that would remain male-dominated until the rise of the Rich White People in Peril school of suspense film punched some holes in its glass ceiling 60 years later. In 1931, when Murder by the Clock premiered, there was no cinematic villain anywhere quite like Laura Endicott. It’s well worth enduring a few threadbare old commonplaces in order to see her in action.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact