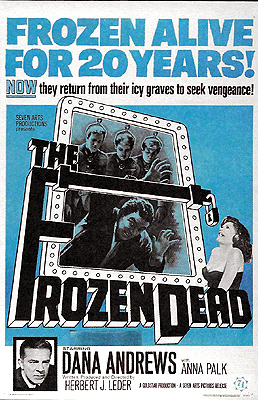

The Frozen Dead (1966) -***

The Frozen Dead (1966) -***

Sore-losing Nazis attempting to get a Fourth Reich off the ground are one of my favorite oft-used premises (albeit not one that comes up frequently in the kinds of movies I write about here), especially when their plans for doing so involve mad science. It’s important that you understand that right up front, because I believe my predisposition toward The Frozen Dead’s central trope accounts for easily 80% of my affection for this cheesy, sleepy, and almost witless little film. Those who are not absolute suckers for this sort of thing will almost certainly be climbing the walls with boredom long before The Frozen Dead limps across the finish line.

Now most sore-losing Nazis hide out in places like Argentina and Paraguay, but not Dr. Norberg (Dana Andrews, from Curse of the Demon and The Satan Bug). No, with the aid and financing of a band of wartime comrades led by General Lubeck (Devil Doll’s Karel Stepanek), Norberg has set himself up in a big manor house outside of London, where he has the privacy not merely to entertain the occasional visit from other fugitive Nazis, but also to continue his work on a project that Lubeck regards as the key to the eventual resurgence of German National Socialism. Norberg’s field, you see, is cryonics, and as the Allied armies advanced on Berlin 21 years ago, his techniques were used to freeze 1500 third- and fourth-string Nazi leaders into suspended animation. Even the doctor doesn’t grasp the scale of the undertaking; he knows only about the dozen men— including his own brother (Edward Fox, from The Cat and the Canary and Skullduggery)— that he found in deep freeze in the basement when he moved into the manor. The trouble, from Lubeck’s point of view, is that although Norberg knew enough in 1945 to freeze a man without subjecting his tissues to irreparable harm, he hasn’t yet figured out how to thaw one out safely. Solving that problem has been the focus of the doctor’s research ever since, with its obvious application to the science of organ transplants furnishing a cover story strong enough for Norberg to operate very nearly in the open.

The transplant blind is doubly valuable for Norberg, too, because he doesn’t live alone. In addition to his assistant, Karl Essen (Alan Tilvern, of 1984 and Rasputin the Mad Monk), and his valet, Josef (Oliver MacGreevy)— both of them fugitive Nazis like their employer— Norberg has a niece by the name of Jean (Anna Palk, from Tower of Evil and The Nightcomers). Jean was but an infant when her uncle slipped out of the Fatherland with her, and much to Karl’s continued annoyance, she’s been brought up to believe that the family and its retainers had been inmates in a concentration camp rather than staff. I think we’re supposed to read just a touch of ambiguity into that deception— to suspect that Norberg’s commitment to Lubeck’s Fourth Reich is less total than that of his comrades. In any event, the mere fact that Norberg can’t currently do what the general requires of him means that his loyalties have thus far been safe from really close examination, his own included.

That’s about to change, though, thanks to Essen’s gross misreading of the latest development around the lab. Eight times now, Norberg has taken one of his experimental subjects out of the freezer and attempted to restart the preserved man’s brain. The first was a total failure, yielding merely a room-temperature corpse instead of a deep-frozen one. With the other seven, the result was a nearly mindless being capable only of performing a single, stereotyped action over and over and over again. One man weeps inconsolably. Another man prays and prays and prays. Still others incessantly mime bouncing a ball, digging a hole, or combing their hair. Norberg’s brother invariably tries to strangle anyone who comes within arm’s reach. The doctor’s theory is that his resurrected patients each became trapped at the moment of awakening in some very narrow and specific memory, for reasons he does not yet understand. But a few days ago, Josef accidentally locked himself in the cryogenic chamber while performing some manner of maintenance on its remaining inmates, and was as thoroughly frozen as any of them by the time his boss discovered him. When Norberg unfroze the unfortunate valet, he awakened unable to speak, or even to think for himself to all outward appearances, but otherwise more or less functional. He could not merely respond to commands, but execute them successfully, provided that the task were something that he already knew how to do before his accident. Essen, comparing Josef to his eight predecessors, and failing to appreciate how their different starting circumstances might affect the results of thawing and cerebral reboot, immediately alerted General Lubeck that Norberg had succeeded at last. Now Lubeck is on his way to the manor in company with a sidekick called Captain Tirpitz (Basil Henson, from The Man Who Haunted Himself), expecting to see a resurrection carried out. Neither the officers nor Norberg are very pleased with Karl once they finish sorting out what happened.

Fortunately, the doctor has some slightly better news to report. Under the cover of his supposed transplant research, Norberg will begin working tomorrow with an American colleague named Dr. Ted Roberts (Philip Gilbert, of Die, Die, My Darling!) to map the machinery of the brain. Roberts recently wowed the medical profession by keeping the severed head of a dog alive, and it is Norberg’s hope that by doing the same thing with an ape, the two of them will be able to tease out the secrets of cerebral microanatomy revealing what he’s been doing wrong thus far when restarting the brains of his frozen patients. You might notice, however (Essen certainly does), that Norberg’s lab is entirely destitute of apes at the moment, and neither Nazi researcher has any very convincing idea of how or where they might acquire one.

That’s when fate lends an unexpected hand. For the past two years, Jean has been in the United States, working on her master’s degree. So far as her uncle knew, she wasn’t due to return for another week, but she managed to wrap things up a little early. Not only does Jean arrive without warning while the manor is crawling with old Nazis, just as Dr. Norberg is gearing up to attempt the surely disappointing resurrection which they’ve come there to see, but she furthermore brings along her new American friend, Elsa Tenney (Spaceflight IC-1’s Kathleen Breck)— who I’m about three-quarters sure is supposed to be Jewish! The girls’ sudden arrival naturally means enormous headaches for all the assembled conspirators, but Essen, world-historic genius that he is, sees it as an opportunity. If Norberg can’t get an ape’s brain to vivisect, than how about an interloping college girl’s? Not Jean’s, you understand— even Karl isn’t so dim as to imagine the doctor would go for that. But by sneaking into Elsa’s bedroom through the secret passages that riddle the house, strangling her, and then framing Norberg’s singlemindedly homicidal zombie brother for the crime, Essen can present his boss with a fait accompli compelling enough to force him into bolder action than he’s inclined to take on his own. The girl’s disappearance can be explained away in the morning by her obvious aversion to the spooky old house full of strangers, and a cover story engineered with the help of “Mrs. Smith” (Ann Tirard, of Stop Me Before I Kill and The Conqueror Worm), a relative of Essen’s and a mistress of disguise, who has settled in the nearest village.

Jean immediately smells a rat, of course. Why the hell would her best friend skip out on her international vacation at the crack of dawn on day one, without so much as a goodbye to her? And beyond that, there are some personal effects remaining in Elsa’s room that she absolutely would not have left behind, even if she were to pull such an absurd vanishing act. Just a minute, though… That Roberts fellow due to arrive later this morning— he’s an American, right? One of the good guys? So he’ll definitely help Jean get to the bottom of everything, I’m sure. HA! Roberts may be a Yank, but he’s also a condescending ass, constitutionally incapable of taking a young woman seriously about anything. And worse yet, he belongs to that breed of B-movie scientist for whom no moral consideration, no matter how lopsided, can ever outweigh the allure of a really impressive technical triumph. When circumstances (and, again, Karl’s bumbling “help”) eventually force Norberg to reveal what’s become of Elsa, Robert thinks it’s about the coolest thing he’s ever seen.

And what exactly has become of Elsa, you ask? Oh man… On a little table in Norberg’s lab, there’s now a sturdy mahogany box, and inside that box is Elsa’s disembodied head, hooked up to an array of life-sustaining machinery, and with a dome of transparent Plexiglas in place of her skullcap to permit the direct examination of her pulsating brain! Also, Norberg has her wired up to about half a dozen cadaver arms left over from his earliest experiments in reviving frozen human tissue, so that she’ll have a “body” to control once he and Roberts work their way up to testing her motor cortex. Norberg claims that Elsa has neither will nor consciousness in her current state, but that third-degree stink-eye she gives everyone whenever her box is opened argues otherwise, if you’re asking me.

You know what else argues otherwise? The dreams of her plight that Elsa telepathically transmits to Jean every night, together with the disturbing psychic effect she seems to have on the defective thawed-out Nazis. Naturally the persistence of those dreams convinces Jean that something unspeakable really has happened to her friend, and if Roberts won’t help despite his rather ludicrous professions of love for her, then he isn’t the only one to whom Jean might turn. Down at the train station, for example, there are witnesses to Elsa’s supposed departure, and what they have to say shoots several fatal holes in Essen’s story. Also, there’s an Inspector Witt (Tom Chatto, of Enemy from Space and Assault) in the village, who finds the testimony of the porter (Charles Wade) and the station master (John Moore, from Countess Dracula and The Devil Within Her) just as interesting as Jean does. And of course there’s always Elsa herself. If there’s one thing cheap mad science movies should have taught us by 1966, it’s never to underestimate either a brain in a jar or a head in a pan.

I suppose it shouldn’t surprise us very much that the nearest British equivalent to The Brain that Wouldn’t Die is starchy, tweedy, and inordinately concerned with the goings on at railway stations. Don’t let any of that obscure, though, how close an equivalent to that notorious movie The Frozen Dead really is. I don’t mean that just with regard to the telepathic severed head who’s forever demanding that somebody destroy her, either. The Frozen Dead also resembles The Brain that Wouldn’t Die in having not a single character who can be described with a straight face as its hero. It has villains aplenty, a whole stable of monsters, a victim, and a damsel in distress, but no upstanding personification of decency and normality to charge in and save the day like one expects in a horror film of the 1960’s. Writer/director/producer Herbet J. Leder seems to have thought he had one of those in Ted Roberts, but the American doctor’s conduct prior to his third-act side-switching is utterly disqualifying. Inspector Witt, meanwhile, is less a hero than a benign opposite to the sort of looming background evils that so often figure in horror stories of all kinds. His role is not to restore the status quo ante so much as to threaten the villains with its restoration merely by existing. What we’re left with, then, is a struggle between an abomination of science and the men who created her, in which characters like Jean and Roberts are little more than pawns. I like how utterly abnormal that is, even if it seems a tad less conscious here than it did in The Brain that Wouldn’t Die.

The Frozen Dead’s wild screwiness at the level of the script might be something like par for the course, though, because we’ve encountered Herbert J. Leder before. Almost a decade earlier, he made his screenwriting debut with Fiend Without a Face, surely the most profoundly bizarre product of Britain’s short-lived late-50’s vogue for aping American sci-fi monster movies. Alas, Leder’s direction lacks even a fraction of the crazed energy that characterizes his writing. In some respects, Josef the brain-damaged valet serves as a metaphor for this whole film, slowly and clumsily doing only what he’s told, and getting it always just the minimum acceptable approximation of right. Post-op Elsa, for instance, can be effectively eerie, but only so long as she doesn’t speak, and provided we don’t get too good a look through her plastic cranium. The freezer full of preserved Nazis has some impact whenever Norberg slides open the steel door separating it from the rest of the lab, but that impact is softened by the pathetically paltry numbers of the Frozen Dead themselves. It would be a little easier to take on faith the small army of similar Nazicles supposedly waiting in the wings if we could see maybe ten or twenty of them stacked up in Norberg’s basement instead of just three or four. And “Mrs. Smith,” the assassin and mistress of disguise who needs all her talents in the latter department to conceal what anti-Nazi partisans did to her face at some point, is just interesting enough a character to make me wish she were a secondary villain instead of a tertiary one.

Finally it would be remiss of me not to mention one more thing before wrapping up this review— The Frozen Dead’s easily missed MVP, Alan Tilvern as Karl Essen. This malicious lackwit, this overeager nincompoop, this inexhaustible fount of half-baked bad ideas is truly Hall of Fame material among incompetent bad-guy sidekicks. Imagine TV’s Frank from “Mystery Science Theater 3000” played perfectly straight, and you’ll understand the vibe Karl gives off as he makes everything calamitously worse for his own side at every turn. The similarity is strong enough, indeed, that I’m shocked to discover that “MST3K” seems never to have shown The Frozen Dead even during the primordial KTMA days. I don’t know. Maybe Joel Hodgson, Mike Nelson, Frank Conniff, or somebody saw this movie as a kid, and had it in the back of their head somewhere while they were developing the replacement for Dr. Larry Erhardt during the run-up to season 2.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact