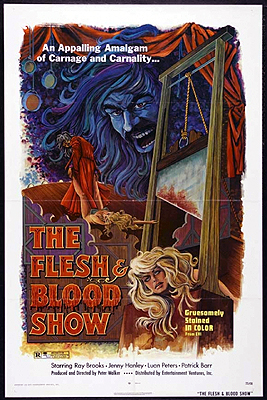

The Flesh and Blood Show (1972/1974) ***

The Flesh and Blood Show (1972/1974) ***

Although Pete Walker is remembered primarily for his horror movies (to the extent that heís remembered at all), that wasnít his first career. Hell, it wasnít even his second or third. The son of radio comic Syd Walker (a fixture on the same show that cursed us with Arthur Askey and Richard Murdoch), he initially tried his hand at the family business. When that went nowhere, Walker turned to acting, and when that went nowhere too, he picked up a movie camera for the first time, and became a pornographer. For several years that meant 8mm one-reelers with titles like Godiva Rides Again and The Woodland Blonde, sold under the counter at skeezy newsstands and bookshops of ill repute. But in 1968, he moved up in the world by writing and directing an extra-sexy crime thriller by the name of The Big Switch. Walker then took a lighter turn with School for Sex, Cool It, Carol, and Three Dimensions of Greta, all softcore sex comedies of the sort that proliferated on British screens with the loosening of censorship at the turn of the 70ís. It was only with 1971ís Die Screaming, Marianne that he took a recognizable step in the direction of the genre in which he left his deepest mark. Die Screaming, Marianne was another thriller, but it abandoned The Big Switchís Swinging London affectations in favor of an incredibly twisted psychosexual modern-day gothic vibe. Between that and the title, it naturally attracted a fair amount of notice from the horror audience, and for his next trick, Walker decided to give that crowd what they had come for, but didnít quite get. The rest is an under-appreciated little cul-de-sac in British cinema history, down which Iíd like to help shed some light now. And since I prefer to begin things at the beginning, how about we start where Walker himself did as a full-on horror director, with The Flesh and Blood Show?

Absolutely nobody watching this film should be a bit surprised to learn that its creator used to be a smut-peddler. Case in point: I strongly doubt that even during the years of highest hippiedom, there were many young women who, upon being awakened at 2:00 in the morning by an unexpected knock on the front door to their flat, would hop straight out of bed to answer it buck-ass nude. Thatís exactly how Carol Edwards (Luan Peters, from Lust for a Vampire and Twins of Evil) rolls, however. But lest we simply mistake The Flesh and Blood Show for more of what was previously Walkerís main stock in trade, Carolís late-night caller (Cellarís David Hovey) has a knife in his gut. Or at least thatís what it looks like at first. Actually, this is an early example of the hoary horror movie gag wherein some dipshit prankster pretends to be a murder victim in order to scare the protagonist. At least John isnít the total stranger for which Carolís roommate and possibly girlfriend, Jane (Judy Matheson, from Crucible of Terror and The House that Vanished), initially takes him. Like the girls, John is an actor, and he met Carol on the set of some cheap fright flick that wrapped recently. Anyway, John stopped by to talk to Carol about a gig he was just offered, an experimental, improvisational play entitled The Flesh and Blood Show. Your guess as to why he picked this of all hours to do so is as good as mine. John is in no position to turn down any work, so heís taking the job no matter what, but it puzzles him that heís never heard of Group 40, the independent production company behind the play, and the plan for the project seems weird even for the indie stage. Although the producers claim to have bookings in the West End lined up, the cast and director are supposed to do their rehearsing in some little seaside village called Eastcliff, at a theater that hasnít been used in some 30 years. As it happens, The Flesh and Blood Show needs no introduction in this flat, for Carol and Jane have both signed onto it themselves despite misgivings similar to Johnís. They donít know any more than he does, either, about the bizarre project or its enigmatic producers. I guess the mystery of Group 40 will just have to wait for later, after everyone has reported to the Dome Theater for the rehearsals.

There are four other players in The Flesh and Blood Showís cast. Tony (Tristan Rogers, from Three Dimensions of Greta and Night Eyes 3), Simon (Robin Askwith, of Horror on Snape Island and Confessions of a Window Cleaner), and Angela (Penny Meredith, from The Ups and Downs of a Handyman and Confessions of a Summer Camp Counselor) are nobodies like Carol, Jane, and John, but Julia Dawson (Jenny Hanley, of Itís Not the Size that Counts and Scars of Dracula) is a nascent movie star whose agent has decided to burnish her resumť by sending her back to the boards. That would seem likely to produce friction between Julia and the others even if the former wasnít a whole day late to the rehearsal. As for Mike the director (Ray Brooks, from Baffled! and Daleks: Invasion Earth, 2150 A.D.), he turns out to know almost as little about the whole undertaking as the actors. All Mike has from Group 40 is a telephone number, a contact name, and a general idea of the themes heís supposed to riff on with the cast as they develop The Flesh and Blood Show into something fit for the West End. Thereís one more unwelcome surprise, too. Eastcliff is a tourist town, and the place is practically deserted in the off season. There isnít even a boarding house up and running for the gang to rent, so theyíre pretty much stuck lodging in the theater itself.

Waitó did I say one more unwelcome surprise? That should have been two. The second, inevitably, is the homicidal maniac who has also come to practice his craft at the Dome Theater this winter. His first victim is Angela, who wanders off for no obvious reason in the middle of the first night to go exploring in the basement which the Dome somehow manages to have even though itís built on an enormous pier. No one even notices that sheís gone until she begins screaming. Itís Mike who finds Angela down there, her body strapped into an apparently all-too-functional prop guillotine and her head slipped into an array of false ones on a shelf not far away. He doesnít want to panic his cast, though, so he leaves them all with instructions to stay put in the auditorium while he goes off ostensibly to search for Angela outside. Actually, he heads straight to the Eastcliff police station, but the killer has of course disposed of the evidence by the time Mike returns to the Dome with a detective and some uniformed cops. The unimpressed Inspector Walsh (Raymond Young) dismisses Mike and his fellows as a nest of long-haired big-city troublemakers.

Julia finally arrives shortly before dawn, thereby missing all but the last of the excitement. A phone call to Group 40, meanwhile, drums up a replacement for Angela with unreasonable celerity. The latter is a local girl called Sarah (Candace Glendenning, also in Horror on Snape Island), and sheís a godsend for the company for reasons above and beyond the speed with which she brings them back up to full strength. Sarahís aunt happens to own a great, big house in the village, and although none of the rooms are ready to receive boarders at the moment, they could be made so in a day or two. Thereís no wait at all on the kitchen or bathroom, meanwhile, and it does Mike and his cast a world of good to be properly fed and washed for the first time since their arrival in Eastcliff. Thus fortified, they hurl themselves back into their work, blow off excess steam with an ill-advised intra-company romance or two, and even acquire an annoying admirer in the form of retired soldier and theater buff Major Bell (Patrick Barr, from Midnight at the Wax Museum and The House of Whipcord). Indeed, the director and cast of The Flesh and Blood Show could be forgiven for believing that their lives had returned to something like normal. But soon Carol is first attacked by a hobo and then murdered by persons unknown. John disappears without a trace at around the same time, leading to the natural conclusion that he was the culprit behind both Carolís murder and Angelaís. Thereís no hiding this turn of events from the cast, nor can Inspector Walsh gainsay the dead girl whom Mike drops in his lap after fishing her out from between the pilings of the pier. And as if all that werenít enough, Group 40 picks this precise moment to vanish into the ether, leaving Mike without support or guidance of any kind. The troupeís travails are not over even now, however. Johnís stabbed and beaten body washes up on the beach in the next town down-current from Eastcliff; the coroner pronounces a time of death which both exonerates the dead actor and demonstrates pretty conclusively that the killer is still at large. Meanwhile, we know (even if the other characters donít) that Carolís murder was proximately provoked by her discovery of two mummified corpses tied together in a closed-off space beneath the auditorium, and that Julia has been spending an awful lot of time lately down at the Eastcliff Public Library, researching a long-ago local scandal involving the Dome Theater and the unexplained disappearances of all three participants in a love triangle focused on the wife of respected Shakespearean Sir Arnold Gates. Thatís the sort of history that usually turns out to be distinctly relevant to the present-day killings in movies like this one.

I have no idea what kind of release Blood and Black Lace, 5 Dolls for an August Moon, or any of the other early gialli received in the UK prior to the advent of home video. Consequently, I canít be sure whether to read The Flesh and Blood Show as a response to them, or as merely an extreme mutation of either the Hammer ďMini-HitchcockĒ formula or the contemporaneous ďshowbiz turned deadlyĒ tradition. Both of the latter had been prominent on British movie screens for more than a decade when Walker and screenwriter Alfred Shaughnessy got to work on this film. Arguing in favor of the Anglo-giallo interpretation are the killerís flagrantly perverse psychosexual motive and his portrayal as a mostly unseen, lurking presence indicated by severe closeups on his gloved hands. (Note that the gloves are made from brown wool instead of black leather. Somehow that detail strikes me as perfectly and deliciously English, even if it never really became a trope so far as I know.) The convergent evolution interpretation, on the other hand, is supported by the offscreen killings, the needless and unconvincing complexity of the murder plot, and the succession of boring, long-winded explanations whereby various characters take turns dotting all the Iís and crossing all the Tís after the killer has been caught. (For that matter, I suppose it argues for an origin free of direct giallo influences simply that the killer is caught, and not slain himself.) Those explanations during the final scenes are also the key mechanism whereby Walker puts his personal stamp on this movie, couched as they are in terms obviously calculated to create some ironic detachment between creator and creation. Subsequent Pete Walker productions would strike their poses of giving a crass and stupid public exactly what it asked for and deserves in the advertising campaigns, but The Flesh and Blood Show does it right in the concluding dialogue.

That was a serious mistake on Walkerís part, and itís a sign of his acumen that he wouldnít repeat it until his final film, House of the Long Shadows. In The Flesh and Blood Show, the elaborate routine of nodding and winking that accompanies the explanatory wrap-up merely serves to expose how critically dependent stories of this type are upon a tacit agreement between teller and audience to take seriously certain things that donít entirely deserve it. Itís especially unfair to the actor playing the killer, who spends the climax pouring his absolute all into a performance that makes no logical or psychological sense whatsoever. He was selling the shit out of it, too, until Walker and Shaughnessy went and pointed out how ridiculous it was!

Until that ill-advised ending knocks things awry, though, The Flesh and Blood Show is a mostly excellent foretaste of what the slasher subgenre would become in the 1980ís, even though it seems to have exerted little specific influence over the subgenreís development. In fact, itís so good that I fear Iím going too easy on it by grading it on the same curve as Deadly Games, Scream, and Silent Night, Deadly Night. Arthur Shaughnessy is to be commended for assembling an array of incentives and extenuating circumstances sufficient to justify Mike and the gangís continued exposure to danger, whether or not it ever rises to the level of realism. First off, they all need the money. Second, they canít initially find anyplace to stay in Eastcliff except for the killerís preferred stomping ground. Then Mikeís plan to handle Angelaís death on the downlow backfires by pissing off Inspector Walsh. And finally, the coincidence between Johnís disappearance and Carolís murder lulls the survivors into a false sense of security by allowing them to pin both killings on the vanished and presumably fled actor. The demure handling of the murders may disappoint gorehounds, but it bolsters The Flesh and Blood Showís mystery aspect by ensuring that we know only a little bit more about whatís going on than the protagonists do. The cast, although uneven and generally of somewhat limited ability, nevertheless gel into a moderately effective ensembleó something you almost never see in a slasher flick. The Flesh and Blood Show is extraordinarily smutty, too, by British standards (for those of us who consider that a selling point in 1970ís exploitation horror), and the performers of both sexes are pleasant enough to look at in that context. And as is so often the case in showbiz-centric fright films, thereís plenty of fun to be had trying to piece together what the show-within-the-show is even about from the motley assortment of disconnected scenes which weíre allowed to glimpse. Itís true that The Flesh and Blood Show gives little indication of the heights that its director would reach two and three years down the line, but itís an auspicious entry into new territory just the same.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact