The House of Whipcord (1974) ***Ĺ

The House of Whipcord (1974) ***Ĺ

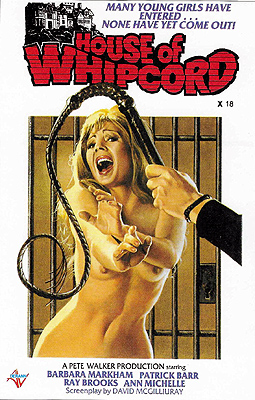

Iíll bet you havenít seen very many like this before. The House of Whipcord is sort of a horror movie, sort of a womenís prison movie, and extremely English all the way around. Despite the external appearances of extreme cheesiness (just look at the box art, man!), itís actually one of the better English exploitation movies that I can recall seeing. It lumbers a bit, in that characteristic British way, but itís relatively fearless in the face of its potentially controversial subject matter, and director Peter Walker seems to have spared not a momentís concern for the sensitivities of the easily offended. This is also a movie with a Message. Even before the main title card is displayed, the following caption appears on the screen: ďThis film is dedicated to those who are disturbed by the lax moral codes of today, and who eagerly await the return of corporal and capital punishment.Ē

The house of the title is actually a disused county prison. As a 19-year-old French model by the name of Anne-Marie DeVarnet (Penny Irving) learns to her great disadvantage, it is only officially disused-- its current owners have found quite a lot of use for it, as a matter of fact. Anne-Marieís troubles begin at a party. A photographer friend of hers has brought along an immense blow-up of a picture he took on their last assignment together in a park somewhere in London. The photo depicts Anne-Marie, naked but for an open trench coat, being led away by the police while large numbers of middle-aged bystanders look on in disapproval. Both Anne-Marie and the photographer were fined a minor sum by the court that tried the case, and so far as they knew, that was the end of that. Just a funny story to tell at a party, right? Wrong. At the party, Anne-Marie meets a distinctly evil-looking, albeit handsome, young man (played by Vampire Circusís Robert Tayman) named Mark Desat. Mark E. Desat. Say it with me, out loud: Mark E. Desat. There you go, you can see heís going to be nothing but trouble.

Anyway, Anne-Marie and Mark make a dinner date, and later, another date for her to meet his parents at their home out in the country. Anne-Marie is very excited, and she tells her roommate, Julia (Ann Michelle, from Psychomania and Young Lady Chatterley), that sheís going away for the weekend. On the drive out, Mark starts acting a little funny. Actually, funny isnít quite the word-- he starts acting like the hooker-slaying madman in The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave did when he was picking up girls. He scarcely utters a word, and he refuses to answer any of his companionís questions regarding where they are, where theyíre going, and how much longer it will be before they arrive. When they finally do pull up to the manorís gate (which looks alarmingly like it was intended to prevent those on the inside from getting out), he leaves her standing next to the car, and disappears into the building. The next thing Anne-Marie knows, sheís being led, most brusquely, through the manorís decidedly institutional-looking interior by an iron-faced woman named Bates (The Haunted Stranglerís Dorothy Gordon). Bates takes her to a small room deep within the building, locks her inside, and tells her to remove all of her clothes, shoes included, and to place them on the table in front of her. All in all, itís very similar to the reception Malcolm McDowell receives at the prison in A Clockwork Orange.

And wouldnít you know it, thereís a very good reason for the resemblance. It seems Anne-Marie has found her way into a highly illegal private prison for young women who refuse to be bound by the time-honored moral standards of their forefathers. This prison is run by a blind, deaf, and senile ex-High Court judge named Desmond (Patrick Barr, from The Satanic Rites of Dracula) and his ex-reform school matron wife, Margaret (Barbara Markham). These, presumably, are the parents Mark wanted Anne-Marie to meet. Margaret and His Honor think the courts let Anne-Marie off too lightly for her public indecency in the park, and they have arranged to have her brought in to receive the punishment she deserves. She is sentenced to confinement for an indefinite period-- its length to be contingent upon her conduct while incarcerated (but it doesnít take Nobel laureate to see that something between a life sentence and a death sentence is in the offing)-- and shown to her cell by Madam Walker (Sheila Keith, of Frightmare and House of the Long Shadows), who is if anything even sterner and more threatening than Bates. The rules of the prison are simple: donít talk to anyone except in response to a direct question or order from the staff, stay on your cot unless and until you are told otherwise, and spend all time not occupied with other duties in the diligent study of the Holy Bible. The disciplinary scheme is equally simple, and follows something like the three-strikes-and-youíre-out model so popular in America today: the first infraction against any of the standing rules or against any instructions from the staff whatsoever will earn you a stint in solitary confinement; the second infraction wins you a good, sound flogging from Madam Walker; the third and final infraction gets you hanged within 24 hours of its commission. And so we settle down to play that ever-popular game of the womenís prison movie, Count the Offenses.

Offense #1: Anne-Marie makes a plot with her cellmate to break out and rescue a third-time-loser named Vaughn (she stole food from the kitchen) before she can be executed. This escape attempt happens way too early in the film to have any chance of success, so it comes as no surprise when Margaret catches the girls down in the death room, trying to untie Vaughn. The infraction status of the three girls is such that we get to see all three phases of the disciplinary regime in action at once. Vaughnís hanging occurs on schedule, Anne-Marie gets her trip to the hole, and her roommate gets her flogging. (Those of you who are as depraved as me may be disappointed to discover that this last happens off-camera.)

Offense #2: Anne-Marie escapes from solitary confinement. She is deliberately allowed to do so by Margaret (acting through Mark) because the matron is convinced that the new prisoner is too dangerous to keep around. She canít simply be killed, however, because of His Honorís stubborn insistence on the rule of law. Thus, Margaret has recourse to goading the girl into breaking the rules. Of course, Anne-Marie doesnít get very far-- this is a trap, after all-- and she gets her date with Madam Walkerís cat-oí-nine-tails.

Offense #3: Another escape attempt, the opportunity for this one provided by Walkerís carelessness rather than Margaretís duplicity. This time, Anne-Marie is actually successful. She sneaks past all five of her captors, scales the wall, and runs off into the night under the cover of a raging thunderstorm. She gets herself picked up by a passing trucker, who means to take her to the police, but who gets second thoughts when he gets a look at the girlís back. Instead, he drives her to what a passing bicyclist tells him is a hospital a few miles out from town. The shot of the trucker pulling up to the ďhospitalísĒ strangely familiar main gate is one of the best ďoh, shit!Ē moments Iíve seen in a movie in a long time.

Meanwhile, Julia has noticed that her roommateís weekend trip has somehow managed to stretch out to nine days. She starts poking around for clues, and is eventually contacted by the trucker who picked Anne-Marie up. He tells Julia that he took her roommate to a mysterious private clinic out in the country, and gives her approximate directions. The next half-hour or thereabouts is unexpectedly exciting, enough so that I would be doing you a major disservice by giving away any more details. Suffice to say that Margaret and company have left a few too many traces for their own good this time, and that they are in for a lot of unwelcome attention.

The House of Whipcord is a surprisingly solid little movie. Itís very well-acted for a film of its type, with entirely believable performances all around. (The sole exception is Markham, who overplays Margaretís descent into utter insanity during the last half of the movie.) The story has a genuine logic to it (watch enough European-made cheapies and youíll really come to appreciate the rarity of that quality), and a number of satisfying little twists as well. I particularly like the wrap-around structure of the movie, which actually begins with Anne-Marie being picked up by the truck driver. Okay, so itís not really that sophisticated, but come on-- look at this movieís context. When was the last time you saw a womenís prison movie that even half-heartedly played around with the chronological sequence of events? I grant you, The House of Whipcord didnít exactly have the voyeur appeal that I was looking for in a movie with a name like that, but itís also nice to be surprised by a movie that turns out to be really good in ways youíd never have dared to expect.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact