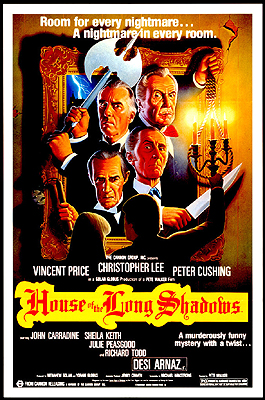

House of the Long Shadows (1983) **½

House of the Long Shadows (1983) **½

I wish I knew with whom the idea to make House of the Long Shadows originated. It was, after all, an exceedingly strange idea, pursued despite its seemingly obvious potency as box office poison, and I’d like to give credit (although I’m not sure that’s quite the right word) where credit is due. Also, it would subtly but importantly change what kind of weirdness we’re talking about if the real instigator were one likely set of suspects versus the other. This film might be a case of two loony producers (specifically Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus) attempting to cash in simultaneously on several mutually incompatible fads, and hiring a writer and director (specifically Robert Armstrong and Pete Walker) either so wrong they were right or so right they were wrong, depending on which angle you prefer to emphasize. Then again, it could also have been a case of a loony creative team taking an impossible project to the one studio in the business whose leaders were mad enough to give it a go. However it worked, though, somebody decided, at a time when horror onscreen was all but synonymous with maniacs wielding garden tools, to film not merely a spooky house mystery, but a spooky house mystery based mostly on a stage play from 1913. Somebody thought the minor vogue for glossy, star-studded adaptations of old-timey detective stories (think Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile, maybe even Radley Metzger’s unloved 1978 update of The Cat and the Canary) implied a demand for a new version of Seven Keys to Baldpate. Somebody believed that the first flowering of Baby Boomer nostalgia created a hospitable environment for a grand reunion of mid-century Horror Geezers while there were still enough of them left alive to justify the effort. And somebody thought not only that those should all be the same movie, but that Walker— one of the few British directors who had truly understood what audiences of the 70’s were demanding from their fright flicks— was the man to make it. Even so, it would have been quite a trick to predict just how weird House of the Long Shadows would turn out. Although it starts as Seven Keys to Baldpate, it quickly zigs into The Old Dark House before taking an even sharper zag through a geriatric variation on Hell Night, only for a triple twist ending to bring it right back to where it began.

Kenneth Magee (Desi Arnaz Jr.) is a best-selling author of “contemporary” fiction. I’m not at all sure what that’s supposed to mean in the context of 1983, and neither the title nor the cover of his latest novel, The Lie, is any help on that score. We can tell what it doesn’t mean, though, from a debate that Magee has over drinks with his publisher, Sam Allyson (Robert Todd, from Asylum and The Love-Ins), at the London club where the latter man is wont to spend his evenings. There’s no gainsaying Magee’s sales figures, of course, but Allyson often wishes he’d try his hand at something big and sprawling, with larger-than-life characters driven to drastic action by grand passions. The kind of thing Dickens or Tolstoy or one of the Brontes would have written, you know? Kenneth counters that the reason nobody, himself included, writes books like that anymore is because they’re unrealistic, unconvincing, and fundamentally childish in outlook. Anybody, or so he contends, could write a book like Wuthering Heights. In fact, Magee claims that he himself could do so in just 24 hours, provided he could lock himself away without distractions in surroundings of suitable atmosphere. Allyson scoffs, at which point Magee offers to make a bet of it: $10,000— no, $20,000— if the publisher can find him the right place to do the work. Upon consideration, Allyson avers that he knows of a spot that should satisfy Kenneth’s particulars, a manor house in Wales abandoned for over 40 years, by the name of Bllydpaetwr. (“It is Welsh, you know. The closest I’ve ever come to pronouncing it is ‘Baldpate’.”) It shouldn’t take Allyson long to make the necessary arrangements, so Magee is on if he’s really fool enough to go through with the wager.

As is only proper, Magee completes the drive to Bllydpaetwr Manor in the darkness of night, against a thunderstorm that reduces visibility to practically nil, and gets good and lost somewhere in the home stretch. And as is only proper, the village surrounding the manor proves to be an unwelcoming place, where such people as are still out and about at the hour when Kenneth arrives are all more interested in discouraging him from visiting the old house than in helping him in any way to find it. Magee initially finds no assistance even at the local train station, because the couple he meets there— Andrew and Diana Caulder (Richard Hunter and Louise English)— are themselves out-of-towners, with problems of their own, and the hooded crone who galumphs silently through the station only to disappear out the window in the ladies’ room is the least cooperative inhabitant of all! Eventually, though, the station master (Norman Rossington, of Frankenstein: The True Story and Raw Meat) deigns to put in an appearance, and gets the increasingly exasperated writer back on track.

Bllydpaetwr Manor lives up to its billing in most respects. It’s big, musty, chilly, dark, isolated, unimproved by electricity (we’ll just agree to pretend we don’t notice all those light switches sneaking into the frame), and generally spooky as hell. If there were any doubt in Magee’s mind that he could speed-write a novel to Allyson’s blood-and-thunder tastes here, it evaporates the moment he sets up his typewriter in one of the many bedrooms. There is one department, though, in which the house seems not to be as advertised. For a place where nobody has supposedly set foot in 40-some years, Bllydpaetwr Manor sure does look lived-in. In fact, there are signs of occupation not merely within the day, but perhaps even within the hour. Kenneth goes searching for intruders, and in short order comes face to face with a positively ancient man (John Carradine, from Crowhaven Farm and Superchick) and a merely elderly lady (this part was written for Elsa “Bride of Frankenstein” Lanchester, but when she proved unavailable, Pete Walker brought in his own personal Horror Geezer, Sheila Keith, whom he’d used so memorably in The House of Whipcord and Frightmare). The aged pair are suspiciously reluctant to introduce themselves, but finally admit to being Elijah Quimby and his daughter, Victoria, the caretakers. Might have known a place like this would be looked after by somebody like these two, huh?

It’s one thing for caretakers to show up unbidden and unannounced, but something else again for complete strangers to start parading through Bllydpaetwr like they own the place. So you can imagine Magee’s consternation when the hag from the train station drops by, letting herself in through the front door with a key which she surely shouldn’t have. This time, Kenneth gives her no time to find a window out which to escape. He seizes the crone as soon as he spots her skulking around the parlor, discovering to his astonishment first that her wizened, beaky face is but a rubber mask, and second that there’s a youngish and fairly attractive woman (Julie Peasgood) beneath it! When pressed, the newcomer identifies herself as Catherine De Corsi, and claims to be on the run from an outfit called the Organization for the Promotion of International Terrorism, operatives for which are also after Magee for some reason. Yeah, Kenneth doesn’t buy that either, and he’s adamant that he isn’t going anywhere, OPIT or no OPIT. And in fact he gets confirmation that “Catherine”— or Mary Norton, to give her her real name— is not who she claims to be when he catches her making a phone call to Sam Allyson! Turns out she’s really the publisher’s secretary, on a mission to divert Kenneth from his purpose, and to preserve Sam’s $20,000. Her conversation with the boss does bring to light hints of a more sinister conspiracy afoot at Bllydpaetwr, however, for according to Allyson, there are no caretakers.

Magee is also quick to disbelieve the yarn spun by his next uninvited guest, a little old man who calls himself Sebastian Rand (Peter Cushing). In Rand’s case, the issue isn’t the plausibility of his story, but rather that he and the Quimbies (whoever the hell they really are) obviously know each other, but are just as obviously trying not to let on that they do. Only with the fifth and sixth interlopers does Magee at last feel like he’s dealing with somebody on the up-and-up. Lionel Grisbane (Vincent Price) is definitely the scion of the grand family that once owned Bllydpaetwr Manor, because only titled nobility could produce a narcissist and drama queen of such magnitude. And Corrigan (Christopher Lee) is at least tentatively credible as the new owner of the house, because he’s even more annoyed to find it unexplainedly full of senescent weirdoes than Magee. Still, Kenneth doesn’t really give a shit what any of his uninvited guests do, or what reason they have for intruding upon his stay at Bllydpaetwr, just so long as they leave him the hell alone to write. After all, he has $20,000 on the line!

Yeah, well, we all know that’s not going to happen. Magee has just gotten back into the groove when Mary barges in on him with a new story about strange noises coming from the upper reaches of the house. Kenneth grudgingly agrees to investigate, resulting in the discovery of an impregnably locked room at the top of the manor’s tallest tower. Mary swears she hears someone breathing on the other side, but Kenneth disagrees. In any event, the trip does bring to light some potentially useful intel, in the form of a series of family portraits which the pair find along their route. These unmistakably depict younger versions of everyone else in the house save Corrigan, and identify them all as members of the Grisbane clan. Indeed, Elijah “Quimby,” far from being anybody’s caretaker, is the current Lord Grisbane himself, while Lionel, Sebastian, and Victoria are his children. Evidently there was a fourth kid as well, by the name of Roderick, but the only evidence of him that Kenneth and Mary find is an empty picture frame bearing his name, which somebody had taken down from its place on the wall and left in ignominious neglect, propped up against the wainscoting. If Magee’s taste in fiction aligned better with Allyson’s, he’d know at once what that means.

But because Magee does not share Allyson’s literary proclivities, he gets to react in completely fresh horror when midnight rolls around, and Lord Grisbane and his offspring at last set about the task for which they have assembled. Way back in 1939, you see, Roderick did something unspeakable to one of the local girls. Because the Grisbanes back then were even more exalted than they are now, Roderick was effectively above the law, but not above his kin’s sense of family honor. The boy had to be punished, but since it would have been scandalous and unseemly to turn him over to the authorities, the family took it upon themselves to pass their own judgment. They locked Roderick away in the tower, with only the minimum of human contact necessary to keep his biological needs satisfied. Food, water, and whatever other essentials he required were slid though a slot cut into the bottom of the door (in that respect if no other, Elijah and Victoria really were the caretakers), but under no circumstances was the door itself to be opened, or the lad imprisoned behind it spoken to or acknowledged in any way. As the months stretched into years, and the years into decades, the maintenance of this grotesque extrajudicial incarceration came to dominate the whole of Grisbane family life, until most of them could no longer bear the sight of each other. But tonight, Roderick’s sentence is finally at an end, and his relatives have returned to release him. I’m sure he’ll be totally ready and willing to let bygones be bygones, right? In fact, though, when Sebastian unlocks the door to Roderick’s cell, there’s no sign of him within! Not only has he escaped, but the conditions inside the chamber suggest that Elijah Grisbane’s youngest son spent the years of his confinement growning up to be competitive with any Michael Myers, Jason Voorhees, or Madman Marz. And in case this isn’t yet obvious, Roderick knew as well has his father or siblings what was supposed to happen tonight, concentrating all of his jailers in one convenient location. Confirmation of how the remaining hours before dawn are likely to go arrives along with the couple from the station, who decided to follow Magee to Bllydpaetwr when it became clear that their train was never coming, and who report an encounter with a fearsome, shadowy prowler on their way to the house.

Nobody who’s noticed my particular hobby horse about the underappreciated link between slasher movies and the Colorful Killer strain of spooky house mysteries will be very surprised to learn that I have considerable affection for a film that transforms the hoariest spooky house mystery of them all into a straight-up slasher flick. Conversely, I’m not a bit surprised that I seem to be about the only person who does. Still, I think the time might at last be ripe for House of the Long Shadows to get something of a reappraisal, now that everything is being remixed, reimagined, mashed up, and script-flipped. In a pop-culture world where Abraham Lincoln hunts vampires, Snow White carries a broadsword, and the Wicked Witch of the West is an antiheroine, maybe there’s room for John Carradine, Vincent Price, Peter Cushing, and Christopher Lee to be body-counted out of existence like a crop of counselors at Camp Crystal Lake.

If I aim to provoke that reappraisal, though, I need to be up front about how often House of the Long Shadows doesn’t quite work. Most importantly, the film’s own creators seem not to have fully appreciated what a potentially potent combination of nostalgia and subversion they had on their hands. The first act does little more than to stumble through a parade of clichés as old as the stars of the picture, and although Robert Armstrong and Pete Walker do have the good sense to poke fun at those clichés, they mostly do so in a lazy, hackneyed way on par with a low-grade Count Floyd sketch on “SCTV.” Given that parody was at least partly the intent during that phase of the film, it reflects poorly on House of the Long Shadows that the 1929 Seven Keys to Baldpate was a great deal funnier. The Old Dark House-like second act, meanwhile, was obviously meant as a tonal bridge between the ostensibly comic opening and the blood-soaked home stretch, but falls short of fulfilling its purpose, due in no small part to the excessively unflappable detachment of Desi Arnaz Jr.’s Kenneth Magee. To be fair, unflappable detachment has been a hallmark of the character since Earl Derr Biggers’s original novel, but no previous incarnation of Magee ever faced stakes this high. Even he should be a little flapped by being trapped in a house with an axe murderer. And by any imaginable standard, just one of the three successive twist endings would have sufficed. (My own choice would have been the first one, but there’s a case to be made for keeping the second instead.)

Once Roderick’s cell is opened, however, and both the killer and Pete Walker get down to business, House of the Long Shadows becomes quite good indeed. There’s something extremely satisfying about watching the oldest pros in the fright film business bring their unique talents to a genre that normally has no use for them, and about seeing two temperamentally opposed schools of cinematic horror collide in this particular way. No one can accuse the Horror Geezers of dissolving into an undifferentiated mass of Expendable Meat. Vincent Price has his florid bombast (he also gets the movie’s one genuinely successful laugh line: “Do not interrupt me when I’m soliloquizing!”), John Carradine has his crotchety irascibility, Christopher Lee has his peevish dignity, and Peter Cushing, in a most unexpected turn, brings to Sebastian Grisbane a bit of the gentle soul described by seemingly everybody who ever knew Cushing in real life. As for Sheila Keith, she gets to play directly opposite her usual type (or at least, her usual type under Walker’s direction) as a maudlin sadsack overwhelmed by regrets both great and small. For once, this is a woman whom you can definitely trust not to eat the neighbors. But of at least equal importance, these are all actors whom we’re used to seeing either as monsters or as monster-slayers, so for Walker to cast them as victims (or potential victims) instead is unsettling on a subconscious level. You keep finding yourself having thoughts like, “Don’t go down those stairs, Lionel! Vincent Price might be down there! Wait— you are Vincent Price…” That might be part of why House of the Long Shadows has been so roundly dismissed since it first appeared, but you should know by now how much I like to be unsettled.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact