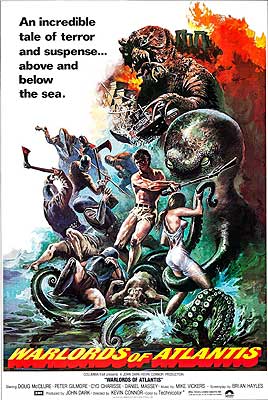

Warlords of Atlantis / Warlords of the Deep / Seven Cities of Atlantis / Atlantis (1978) **½

Warlords of Atlantis / Warlords of the Deep / Seven Cities of Atlantis / Atlantis (1978) **½

I wonder how many of these things are out there, lying in wait for me to stumble upon them? If you read my review of Paul Shrader’s Cat People a couple years ago, you might recall that that movie originated as an Amicus project, but was left high and dry in an advanced stage of preproduction when the studio went out of business in 1977. That’s the genesis of Warlords of Atlantis, too. This movie was more in keeping with the firm’s overall direction at the time, however, which may go some way toward explaining how quickly it got rescued from the trash pile by EMI. Unlike Cat People, which still had years of Development Hell ahead of it, Warlords of Atlantis was delayed hardly at all by the demise of its original backers. Although not directly based on the writings of Edgar Rice Burroughs, it was very much the same sort of picture as The Land that Time Forgot, The People that Time Forgot, and At the Earth’s Core— all of which were much more successful at home than I realized, for all the good that ultimately did Amicus. Like those films, Warlords of Atlantis uses a mishap during a mundane adventure to catapult its protagonists into a fantastical one, involving a Lost World setting, an ancient society whose very existence is unsuspected in the outside world, and a menagerie of monsters brought to life by extravagantly crappy large-scale puppets. At the same time, though, it modernizes the formula a bit by throwing in all of its era’s favorite forms of paranormal hooey, including ancient aliens, magic crystals, psionic powers, and the Bermuda Triangle!

The clipper ship Texas Rose and her crew have been hired by Professor Aitken (Donald Bisset, from Eye of the Devil and See No Evil) and his son, Charles (Peter Gilmore, of The Abominable Dr. Phibes, coming across as the Poundland knockoff of David Warner), to take them into the ill-omened waters southwest of Bermuda, but the scientists have been suspiciously tight-lipped about their motives for the expedition. All they’ve told Captain Daniels (Shane Rimmer, from Arabian Adventure and The People that Time Forgot) is that they intend to test the latest invention of Charles’s engineer friend, Greg Collinson (Doug McClure, of Firebird 2015 A.D. and At the Earth’s Core): a diving bell capable of unprecedented descents into the ocean’s depths. That being so, one wonders why Daniels accepted the gig in the first place, especially since he hasn’t shut up about the area’s propensity for shipwrecks and mysterious disappearances since setting sail. Just the same, the skipper’s griping hasn’t gotten in the way of him or his men doing their jobs long enough to drop Collinson’s contraption over the gunwales with him and the younger Aitken inside, at coordinates designated by the elder.

The diving bell performs well enough that Charles quickly convinces Greg to take it down all the way to its designed maximum service depth. That gets the men into some trouble— not due to any unexpected weaknesses in the machine, but because the additional plunge brings them to the attention of the first of this movie’s monsters. No sooner has the fathomometer hit the red line than a creature looking somewhat like a cross between a Plesiosaurus and an oversized Tully monster swims up from below, evidently mistaking the diving bell for some kind of huge, free-swimming shellfish. Aitken identifies the thing as a placoderm, but it resembles one of those no more than the customized alligators and monitor lizards in Irwin Allen’s version of The Lost World resembled the Tyrannosaurs and Brontosaurs that they so unpersuasively impersonated. Regardless, Collinson manages to drive the monster off by electrifying the bell’s outer hull, after which the bathynauts find at last what they really came looking for. In the face of an undersea cliff, just a few yards below the diving bell’s maximum safe depth, is the mouth of a titanic cavern, and atop an outcropping of rock in front of that is a monument suggesting a crudely formed totem pole made of apparently solid gold. That’s right— here, at the bottom of the Bermuda Triangle, is the gateway to Atlantis!

The men of the Texas Rose get entirely the wrong idea when they see the artifact that Aitken directs them to hoist to the surface along with the diving bell. Not without justification, the sailors leap to the conclusion that the scientists’ secrecy about their objectives was meant not to secure the crew’s cooperation with a mission they’d have rejected as absurd if it were described openly, but rather to bamboozle them into providing transportation for a treasure hunt without sharing in the spoils of its success. Nor are they mollified by Aitken’s protest that the giant old pillar is destined for exhibition in a museum, rather than for sale at a profit. The whole crew save for Sandy, the ship’s boy (Ashley Knight, who played a small part as a Victorian rentboy in an extra-obscure version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde), rises in mutiny; Collinson and Aitken the Younger wind up locked inside their own diving bell, and thrown back overboard; and Aitken the Elder is shot dead when he raises a fuss. But while all that’s going on, even bigger trouble is brewing at the bottom of the sea. That cave Greg and Charles saw earlier? It’s home to an octopus at least as big as the Texas Rose. The monster emerges to seize the diving bell in one of its vast tentacles, then follows the machine’s rigging to the surface. Once there, it plucks Daniels, Grogan (Outland’s Hal Galili), Fenn (John Ratzenberger, of Motel Hell and Battletruck), and Jacko (Derry Power, from The Fantasist and Rawhead Rex) from the deck of the ship.

To the considerable surprise of all concerned, however, the octopus neither drowns nor eats its victims, but deposits them safely in an immense air-pocket cavern communicating with its lair. There, mutineers and mutinied-against alike are rounded up by a squad of strangely equipped soldiers under the command of an Atlantian nobleman called Atmir (Michael Gothard, of Lifeforce and Who Slew Auntie Roo?), and marched off to Troy (but presumably not that Troy), one of the Seven Cities of Atlantis. It’s an open question at this point whether the surface folk should consider this captivity or rescue from the dangers teeming outside the city walls— or indeed whether that distinction has any practical meaning under the circumstances. Consequently, there’s also no telling how much difference it makes to anybody’s fortunes when Collinson gets them all no-two-ways-about-it jailed for stirring up trouble in Troy’s marketplace over the mistreatment of a girl named Delphine (The Lifetaker’s Lea Brodie) by some of Atmir’s men.

Aitken, however, is quickly singled out for special treatment, evidently because Atmir thinks the rulers of Atlantis would like the cut of his jib. The scientist alone is released for an audience with Atsil (Cyd Charisse, of all people!), one of the rulers in question, who gives him a tour of Troy’s better neighborhoods while filling him in on the salient points of her people’s history. So while his companions learn that they’ve been earmarked for surgical modifications suiting them to lives of menial labor in Atlantis, Aitken learns instead of the Martian origins of the Atlantian aristocracy. He learns how the ancestors of Atsil’s people fled their dying world millennia ago, but became stranded on Earth when an accident befell their space ark. Most of all, he learns of the Atlantians’ long-range plans for Earth’s native inhabitants. Evidently much Martian technological know-how has been lost over the ages, and in order to get it back for the sake of continuing their long-interrupted voyage, the rulers of Atlantis intend to enlist Terrestrial talent and ingenuity— but not at all in the way you’d naturally expect. No, Atsil and her fellow archons are scheming to engineer the rise of a world-subjugating, eugenic, military state among the peoples of the surface world, a state whose expansionist drives will force an unprecedented acceleration of technological development, not only among the conquerors, but also among their neighbors who would prefer not to be conquered. Now that might sound perfectly horrendous to those of us who remember the 20th century. Charles Aitken, though, hasn’t even made it to the First Sino-Japanese War yet, and he’s kind of into the idea, to tell you the truth.

Collinson, fortunately, will get a chance to set Aitken straight. While locked up to await the installation of his brand new gills, Greg extends his new friendship with Delphine to include her father, the long-lost captain of the famous ghost ship Mary Celeste (Robert Brown, from The Abominable Snowman and Demons of the Mind). Indeed, it’s those two who inform him and the Texas Rose sailors of the fate that awaits them at the hands of the Atlantian surgeons. Delphine and her dad also take it upon themselves to help the prisoners escape in the confusion that breaks out when Troy comes under attack by a pair budget kaiju. Daniels and his men might prefer not to wait for Collinson to find and rescue Aitken, but since none of them know how to operate the diving bell that offers their only hope of returning to the surface, it isn’t as if they can leave without him. Then it’ll just be a question of surviving the gantlet of rampaging monsters, pursuing soldiers, and deadly topographic hazards standing between them and Collinson’s machine. Oh— and I suppose it’ll also be a question of whether the men’s shared ordeal in Atlantis will be enough to outweigh the small matters of mutiny and murder awaiting unresolved above the waves…

I can’t help but admire the chutzpah of a junky fantasy adventure movie crediting Martians from Atlantis for planting the seeds of Nazi Germany. Make no mistake, either— that is explicitly what Atsil and the other Altantian princelings have in mind when they talk about engineering the rise of a conqueror state among the surface-dwelling nations of Earth! I have no idea, though, whether screenwriter Brian Hayles or director Kevin Connor intended to imply what they did by making Charles Aitken so receptive to the visions Atsil shows him of the Atlantians’ preferred future. The whole thing could, after all, have been meant merely as a riff on 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, in which Professor Aronnax finds himself sorely tempted to abandon both his former life and his present companions in favor of the unprecedented scientific opportunities on offer to him as the naturalist-in-residence aboard the Nautilus. Nevertheless, Atsil is proposing a very different bargain from Captain Nemo. To spend his final decade or so in quest of the secrets of the deep onboard the submarine would merely have required Aronnax to turn a blind eye to the havoc wrought by Nemo’s personal war against warfare. But Atsil wants Aitken to become an honorary member of the Atlantian ruling caste, taking an active hand in bringing about the era of worldwide strife and tyranny which her people’s plans require! Consequently, when Charles is moved to rapture by the montage of distorted Third Reich newsreel footage beamed into his brain by the crystal helmet that Atsil gives him to try on, one can’t help but wonder suddenly how much of this guy’s home library is devoted to phrenology, eugenics, and “race science.” Deliberate or not, it occurs to me that a scientist from Victorian England getting a raging hard-on for the Ghost of Fascism Yet to Come is far and away the most credible thing in this otherwise whimsically ludicrous film.

I wanted to like all three of the Amicus Edgar Rice Burroughs movies more than I did, and the same is true for Warlords of Atlantis as well. Don’t get me wrong— it’s an entertaining little flick. But it had the makings of the ultimate 1970’s Lost World movie, and it never manages to become that. The multi-layered screwiness of the premise is right up my alley, the monster puppets are impressively fanciful in concept (even if they leave a great deal to be desired in execution), and there are some vivid flashes of creativity in the production design. The latter two points are especially to be commended, because a film like this one in the 1970’s could absolutely have gotten away with yet another offering of dinosaurs and Doric columns instead. The funding boost from EMI helped, too, for although Warlords of Atlantis still looks cheap in comparison to the B-movies on A-budgets that had started coming out of Hollywood in recent years, it looks positively lavish in comparison to the final crop of Amicus productions.

Alas, though, Kevin Connor still comes across, much as he did in those earlier films, like a tone-deaf conductor. Although he made a total of five fantasy adventure movies during the early phases of his career (plus the best episode of the deliriously uneven sword-and-sorcery spoof, “Wizards and Warriors”), it feels like he didn’t really get the genre the way he got the horror movies that were Amicus’s previous stock in trade. Certainly he never got the hang of it, except perhaps when he was allowed to make fun of it. In particular, Connor had no knack at all for the kind of action sequences these movies require, in which the stuff happening on the soundstage has to be integrated later with effects footage shot, most likely by some second-unit jobber, on a miniature set somewhere else altogether. Scenes like the “placoderm” attack, the march through the creature-haunted swamps of Atlantis, and the kaiju siege on Troy are just clunky, even if we allow for the weaknesses of the monster puppets.

And speaking of clunky things, Warlords of Atlantis did itself no favors by casting Doug McClure as one of its dual leading men. There was really no excuse for that, either, since by this point McClure had already slopped his way through the whole Amicus Burroughs trilogy like 170 pounds of room-temperature oatmeal. Mind you, Peter Gilmore is no great shakes, either, but his performance at least has some life to it. McClure, on the other hand, is routinely out-acted by the monster puppets. And crucially, Warlords of Atlantis has no one else flamboyant enough to cover for him the way Peter Cushing and Caroline Munroe did in At the Earth’s Core. The most this movie can offer in that direction is Cyd Charisse, showing off the best gams you’ve ever seen on a 56-year-old lady, and Michael Gothard not quite managing to punch through the underdevelopment of his part as the main hands-on villain. The latter might be the sorest point for me, because I just recently watched my way through the early-70’s ITV series “Arthur of the Britons,” in which Gothard was consistently the best thing about the show as Arthur’s Saxon brother-in-arms, Kai. All in all, Warlords of Atlantis is the sort of film that requires you to get over your annoyance over what it might have been before you can start appreciating what it actually is.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact