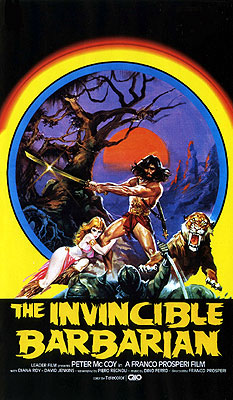

The Invincible Barbarian / Gunan, King of the Barbarians / Lost Warrior / Gunan il Guerriero (1982/1983) -**½

The Invincible Barbarian / Gunan, King of the Barbarians / Lost Warrior / Gunan il Guerriero (1982/1983) -**½

For me, one of the most baffling minor mysteries of exploitation cinema is why Italian barbarian movies of the 1980’s are all so resolutely bad. After all, during both previous vogues for movies about wandering strongman heroes, first in the silent era, and then again in the late 1950’s and early-to-mid-1960’s, Italian filmmakers had just about owned the whole waterfront. Furthermore, at least a few late luminaries of the Great Italian Rip-Off Machine had been around to see firsthand how things had been done during the mid-century peplum boom. So why was it that when Conan was the standard-setter, rather than Maciste or Hercules, their efforts in the same vein yielded such pitifully meager results? The Invincible Barbarian offers no answer to the question; it merely poses it in especially stark form. Director Franco Prosperi had made decent enough movies before, and he got his start as the sidekick to a genuine master, serving as Mario Bava’s assistant director on The Evil Eye and (more to the present point) Erik the Conqueror. Whatever else we might say about him, he was no clueless novice. Star Pietro Torrisi was another old hand with obviously relevant experience. Although he never got a chance at a leading role in those days, Torrisi spent his youth playing small but conspicuous parts in one 60’s gladiator flick after another. Much the same could be said for supporting players like Emilio Messina, Fortunato Arena, and Giovanni Cianfriglia, although their stock in trade had been Spaghetti Westerns rather than peplums. Even writer Piero Regnoli, to whom I give the biggest share of the blame for The Invincible Barbarian’s shortcomings, has very little excuse. He’d been one of the industry’s busiest scribes going all the way back to the 50’s, and if his most recent work by the early 1980’s had mostly been hot garbage like Burial Ground and City of the Walking Dead, he could also claim credit for The Devil’s Commandment. And yet despite all the collective experience and expertise behind it, The Invincible Barbarian fails to meet even the lenient benchmarks set by Conquest or Luigi Cozzi’s Hercules.

We begin (well, we’re supposed to begin— more on that later) with a mystical narrated prologue describing the creation of the universe, the rise of life on Earth, and the dawn of humankind. There’s also some vague and confusing bullshit about “illuminations,” “millennia,” “moons,” and “generations,” all of which plainly refer to time-periods, but none of which seem to refer to the ones you might intuitively attach to such terms. (For that matter, their meaning doesn’t even seem to be consistent from one utterance to the next.) And most importantly for the remainder of the film, there are cryptic references to a prophecy (oh no…) foretelling the birth of a Star Child (called “Gunan” in the Italian version, but “Zukhan” in the English-language export dub)— an invincible warrior who will arise from among the barbarian Zolpan people (all spellings in this review are best guesses, which seems to be equally true for everybody writing about The Invincible Barbarian in English) to do… well, some kind of hero shit, anyway. Maybe they’ll tell us later.

We will anticipate the significance, then, when Prosperi takes us to the yurt where a woman named Mina (I think this is Italian disco singer Marina Marfoglia, who also appeared in Nero) is straining in labor. Mina, her midwife (Alba Maiolini, from Seven Blood-Stained Orchids and The Other Hell), and her apparent husband, Mevian (Fortunato Arena, of Bloodstained Shadow and Poppea’s Hot Nights), are alike in expecting the child to be the prophesied Zukhan, so they’re all rather flummoxed when Mina delivers a pair of fraternal twins. The prophecy never said a fucking thing about that! There’s no time to ponder the import of the surplus baby, though, because bearing down on the Zolpan village at this moment are the Hungat, nomadic plunderers led by the cruel Nuriak (or the cruel Magen, if you’re watching in Italian; either way, he’s played by Emilo Messina, from King of Kong Island and The Ten Gladiators). They too are expecting the birth of the Star Child, only Nuriak, being a villain, intends to kill him before he gets the chance to grow into a hero. Mevian dispatches the midwife to carry the kids to whatever safety she can find while he rallies his tribesmen to defy the Hungat. The disorganized Zolpan rabble are no match for Nuriak and his well-armed horsemen, however, and although Mina’s midwife does indeed escape with the twins, the baby boys will be the sole survivors of their people once their aged protectress expires from the exertions of her flight into the wilderness.

At first it looks like a lucky break when the twins are found and taken in by a tribe of immortal, magic-wielding Amazons known as the Kuniat, but it turns out there was more than just luck involved. Among the Kuniat, second only to the queen herself (Rita Silva, from New York Ripper and The Erotic Dreams of Cleopatra) is an astrologer by the name of Marga (Malisa Longo, of Sexy Sinners and The Red Monks). Marga’s studies of the heavens told her that the Star Child would be born this day, and that his enemies would drive him into the land of her people. Again, though, the heavens said nothing about a second infant, nor do any of Marga’s efforts at divination once the boys have been found reveal which is the actual chosen one. The only person who knows why is the narrator from the prologue, who intrudes once again to explain (if you can call it that) that the stars are pissed off at humanity for fucking up their messianic scheme. I’ll try to be more helpful than the film itself by telling you up front (rather than saving it for another, yet later, exposition dump) that the twins’ parentage is at issue. One of them is Mevian’s kid, but the other is Nuriak’s; Piero Regnoli can’t make up his mind which man seduced Mina away from the other, but the point is, she sinned against the stars by falling for it. Now the spirit of Zukhan has decided to sulk somewhere out in the cosmos until such time as one kid or the other proves himself worthy of being its host, and in the meantime the elements make nature’s displeasure felt by wracking the Earth with all manner of catastrophes. As for the boys, they’re doomed to an existence of constant competition in everything, neither one of them receiving so much as a name unless and until he can seize it from his brother.

I gather that we’re supposed to interpret the ensuing jump through time as landing us at the twins’ coming of age. But since the boys have grown up to be Pietro Torrisi (Death Smiles on a Murderer, The Legend of the Wolf Woman) and Giovanni Cianfriglia (Castle of Blood, The Seven Magnificent Gladiators), both of whom are conspicuously in their 40’s, my mind immediately started tossing off visions of 25 years’ worth of failed rites of passage. What really is fairly explicit is that neither lad has done anything in all his youth to indicate divine favor, so that there’s nothing for it now but to pit the brothers against each other in a trial by combat. The winner will receive (1) the name of Zukhan; (2) an amulet authenticating his identity as the Star Child, since birth certificates haven’t been invented yet; (3) the Sword of the Stars, which the Kuniat have apparently had in safe keeping since time immemorial; and (4) a session with Marga’s scrying pool, which will reveal to him the secret of his origin and the identity of his mother’s killer. One look at the brawny Torrisi and the gristly Cianfriglia should be enough to tell you which twin is coming out on top in a standup fight, and the weaker brother doesn’t have it in him to win by guile, either. That said the Brother Never to Be Known as Zukhan seems to recognize after the fact that dirty tricks and treachery would have been a more successful strategy, for he spies on Marga and his twin to learn about Nuriak and their mother, steals the amulet from his brother while the latter sleeps, and then sneaks off into the night to claim for himself the revenge that the stars intended for Zukhan. (Oh— did I not mention yet that the prophecy is just some weaksauce shit about when, where, and how a two-bit barbarian chieftain is destined to die? Well that’s okay. The screenwriter won’t be mentioning it for another half-hour, either.) Alas, the Brother Never to Be Known as Zukhan forgets everything we just saw him learn about sneakery once he catches up to Nuriak on one of his apparently periodic King Herod sweeps of the local nomads. Nuriak’s minions kill the shit out of him from behind while their boss listens, not a bit impressed, to the would-be avenger’s challenge.

Now it’s the real Zukhan’s turn, but his first foray against Nuriak doesn’t go well. Sure, he makes an absolute terror of himself laying ambushes against isolated parties of Hungat troops while working his way over the hills and across the valleys to his enemy’s lair in the Parco dei Mostri. Once he’s face to face with Nuriak, however, he completely forgets that he’s fighting a whole army, and takes an arrow in the back from a no-name goon during what he intended to be the final showdown. Only his reputation saves him from being finished off as he limps back home to convalesce under Marga’s care.

While Zukhan is down, Prosperi and Regnoli take a reel or two to answer a question that I hadn’t even thought it worth the bother to ask: how exactly do the immortal but not invulnerable Kuniat keep up their numbers in such a hostile and deadly world without any men— especially since they regard themselves as too holy to suffer the defilement of a male’s touch? Turns out they make slave raids on the neighboring tribes to kidnap their most promising maidens, then turn the captives loose to be raped and impregnated in a sort of nature preserve stocked with degenerate, animalistic men! The girl babies are kept to be raised as Kuniat, while the boys are presumably dumped in Rapewood to grow up into more horny savages. Zukhan returns from his ill-fated attack on Nuriak just as a new shipment of girls is being marched into the Kuniat village, and he quickly falls for an exceedingly appealing one called Lenne (Sabrina Siani, from Conquest and The Sword of the Barbarians). That gets Zukhan into trouble on two fronts. For one thing, it happens that Marga develops the hots for him while nursing him back to health, and she’s most displeased to see her charge lavishing his attentions on the breeding stock instead. And more importantly, Zukhan goes and rescues Lenne from fulfilling her intended function, killing three of the tribe’s prize impregnators while he’s at it.

That would mean Zukhan’s ass were it not for an inconvenient Kuniat law against administering the death penalty to one’s own relatives; there isn’t a woman in the tribe who doesn’t consider him her foster son or some such thing. The queen therefore orders him banished— but the recalcitrant man counters that he isn’t going anywhere without Lenne, and that he’s prepared to fight to the death any woman who tries to tell him otherwise. Marga, fully overwhelmed by jealous spite at this point, argues against even entertaining such a notion, but the queen sees no reason not to give Zukhan his way in the unlikely event that he somehow overcomes one of her warriors. He nearly does it, too. Only the stunning effect of the sunlight reflecting off his opponent’s magic shield enables her to get the best of him. I’m assuming his performance in the duel is the reason why the queen changes her mind about kicking Zukhan out of the tribe even though he lost in the end, but that might just be me attempting to impose sense and pattern where none exists. Marga means to be rid of Zukhan, however, by fair means or foul. That night, she takes Lenne, and rides with her to the Hungat stronghold. Nuriak is understandably suspicious of Kuniat bearing gifts, but not too suspicious to jump at a chance to lure Zukhan back into his clutches for a rematch.

There are two drastically different versions of The Invincible Barbarian in English-language release, and unfortunately, the wrong one is much the easier to come by nowadays. If you watch this movie under the title, Gunan, King of the Barbarians (which is what it’s called on at least two different streaming platforms), you’re merely asking for trouble. For one thing, whoever did the mastering for Gunan understandably wanted to present it in widescreen, but had only a 4:3 VHS release as their source material. (I suspect it was a British tape from after the Video Nasties era, but I obviously can’t prove that.) Rather than working honestly with what they had, they took the cathode-ray-tube-shaped image, and cropped the top and bottom until it would fit a modern television screen instead. Given that the source print had already lost both its sides to a none-too-artful job of panning and scanning, the result is like trying to watch the movie through a goddamned keyhole. The Gunan version is heavily censored, too, cutting out most of the rather effective gore and virtually all of the originally copious nudity. Most of the ten minutes (!) of cuts excised neither tits nor blood, however, but all of the numerous flashbacks, dream and vision sequences, and narrated interludes. There were two reasons for this, so far as I can tell. On the one hand, I’m sure the editors of Gunan, King of the Barbarians thought they were quickening the pace, and figured nobody really wanted to sit through all that shit about “illuminations” anyway. But of at least equal significance, every time the narrator shows up, he brings along footage from some other movie, to which the producers had no legitimate right whatsoever. I wasn’t able to place all of it, but anyone likely to watch this film would be sure to recognize at least the pterosaur fight from One Million Years B.C. Realistically speaking, it was never going to be worth any distributor’s while to pay off all the rightsholders who might object, so I can’t say I’m surprised to see that stuff excised from Gunan, King of the Barbarians. Without it, though, the film is totally incomprehensible, since those segments contain literally all the exposition in the entire picture. All things considered, then, this is one of those edge cases in which El Santo wholeheartedly endorses the cool crime of piracy. If you can’t find an old VHS copy bearing the title, The Invincible Barbarian, then hunt up a gray-market DVD and accept no substitutes.

Mind you, The Invincible Barbarian still won’t be a good movie if you find it uncut, but it will at least meet the minimum standard requirements for its genre. It might even do a bit more than that, if you like your sword-and-sorcery leavened with 70’s Eurocomics shroomhead mysticism. Pietro Torrisi is an interesting choice for a post-Conan hero, since his physique is less Arnold Schwarzenegger than Bartolomeo Pagano. He looks like he got his muscles by manhandling freight rather than pumping iron, whether or not that’s actually true. And in English at least, he benefits from being dubbed by Gregory Snegoff, a professional voice actor of real ability. The result is a somewhat more memorable composite performance than one might expect. Emilio Messina is a fun villain as Nuriak, if not an especially intimidating one. I feel like there’s some possibly inadvertent honesty in portraying a prehistoric warlord as a fat, aging lout who used to be scary back when he was young and hungry. Sabrina Siani was obviously cast primarily because she looks stunning in a g-string, but sometimes that’s enough. The action choreography is undistinguished, but it’s apparent even in pan-and-scan that some effort was originally put into blocking and composing the fight sequences. The gore, as I said, is often quite good, even if the weapons supposedly inflicting it often look about two steps up from sci-fi convention cosplay props. But where The Invincible Barbarian really shines is in the sheer weirdness of the writing. Piero Regnoli being Piero Regnoli, I can’t quite believe this is deliberate, but I legitimately love how the Kuniat, although functionally the good guys in this story, can’t plausibly be considered so by our standards, due to their reliance on institutionalized kidnapping and rape to maintain their population. It’s exactly the kind of moral Bizarro World that one often encounters in ancient mythology. Then there’s the Regnoliest feature of the whole film, the punchline in which it is revealed that the Sword of the Stars would become known, vaguely defined eons down the line, as Excalibur. The passage of narration establishing that turn of future events is phrased and positioned so as to imply that the sword was the real protagonist all along, and that we were all following the wrong story for the last hour and a half. That’s some masterful anti-writing right there, of the sort for which I’ve come to rely on Regnoli since I first saw City of the Walking Dead all those many years ago.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact