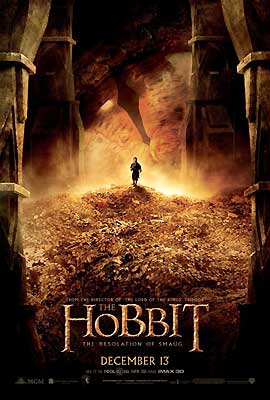

The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (2013) *½

The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug (2013) *½

The Hobbit: An Unexpected Journey left me guardedly hopeful that Peter Jackson wasn’t going to fuck up too badly on his fool’s errand to expand a novel of modest size and ambition into a sprawling and pompous trilogy. With The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug, Jackson dashes every bit of that hope, as thoroughly as the titular dragon once laid waste to the city of Dale. Roughly 30% of this movie’s needlessly vast length derives in any meaningful way from J. R. R. Tolkien’s inaugural book about Middle Earth. Another 15% or so comes from The Lord of the Rings, either references dropped in the main narrative or back-story sketched out in the several appendices to The Return of the King. Then there’s a smidgen devoted to an artless and irritating love-triangle subplot, completely original to the film, contrived for the sake of introducing at least one female character of any consequence to a story that had originally been a total sausage-fest. But the majority of this second Hobbit movie, sadly, consists of overlong and overly intricate action sequences, apparently intended to render it palatable to fans of Van Helsing or A Good Day to Die Hard. A better title for this witless and hyper-caffeinated exercise in overkill would be Hobbit X-Treme!.

The prologue seems really strange at first. As we know from the first movie, aspiring Dwarf-king Thorin Oakenshield (Richard Armitage again) is on a quest to reclaim his ancestral homeland of Erebor from the dragon Smaug (who speaks with the voice of Star Trek: Into Darkness’s Benedict Cumberbatch). Now, however, we learn that the quest was not Thorin’s own idea; rather, he was put up to it by the wizard Gandalf (still Ian McKellan). This retroactive deformation of the central narrative is Tolkien’s own, however, tucked away in one of the aforementioned appendices. It was a bad idea, but it makes sense that it would be included by whichever of the 40,000 credited screenwriters are actually responsible for the current script when you remember how hard this version of The Hobbit is striving to work as a prequel to Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings. The object is to tie this story to the other by saying that it’s really about preventing Smaug from becoming the ultimate weapon of the Necromancer of Dol Guldur (also Cumberbatch’s voice, but mated this time to a CGI effect swiped from House on Haunted Hill)— who, as Gandalf and his fellow wizard, Radagast (Sylvester McCoy), will spend much of the film trying to prove, is really the recrudescent Dark Lord Sauron.

Then we’re dropped into the first of those arbitrary battle scenes I warned you about. A year later, the quest is in full swing, and Thorin, Gandalf, a dozen other Dwarves, and the Hobbit Bilbo Baggins (Martin Freeman, who has the role all to himself this time) are fleeing eastward from a band of Orcs led by Dwarf-slayer extraordinaire Azog the Defiler (a returning Manu Bennett). But as Bilbo discovers while scouting behind the party to check the Orcs’ progress, there’s something else equally worrisome at large— the biggest fucking bear he or anyone else in Middle Earth has ever seen. That news leads Gandalf to suggest seeking shelter at a nearby house he knows about. The owner isn’t fond of Dwarves, but he likes Orcs even less, and he and Gandalf are old friends. They should be safe there from the giant bear as well, because this buddy of Gandalf’s— Beorn (Mikael Persbrandt) is his name— is the giant bear. Or at least he is some of the time. On other occasions, he’s Sweetums from “The Muppet Show.” (This is the one instance in five Middle Earth movies of Jackson’s creature-creators going really seriously astray.)

Beorn does indeed prove a gracious host, and even lets the travelers borrow a horse and a herd of ponies to keep them well out in front of Azog for the next leg of the journey. Unfortunately, the leg after that leads through the dense forest of Mirkwood, where the only reliable trail is too choked by the encroaching trees for mounts to be of any use. And even more unfortunately, Gandalf will have to leave Bilbo and the Dwarves to their own devices while he meets up with Radagast to investigate that Necromancer business. The wee folk should be okay, though, if they stick tenaciously to the path. Right. So, any bets on how long it takes them to wander clear of it, then? No sooner do Thorin and company realize their mistake than they are set upon by giant spiders, and no sooner do they fight their way out of the monster bugs’ clutches than they are set upon by the intensely xenophobic Elves of Mirkwood. At first it looks like maybe Tharanduil the Elf-king (Lee Pace) will free the Dwarves as part of a bargain over the dragon’s treasure hoard (Thorin’s people weren’t the only ones Smaug plundered over the centuries), but Thorin has a grudge against Tharanduil for denying his tribe asylum when they were first driven out of Erebor. The talks break down swiftly, and into the dungeons the Dwarves go.

This is where that love triangle I mentioned first arises. One of the Dwarves’ jailers is Tauriel (Evangeline Lilly, from Real Steel and Freddy vs. Jason), with whom Tharanduil’s son, Legolas (Orlando Bloom)— remember him?— is infatuated. The king won’t have any of his kinfolk consorting with commoners, though, so Tauriel is under strict orders not to encourage Legolas in his affections. Tauriel, rather to her astonishment and much to the prince’s disgust, finds herself strangely attracted to Kili (Aidan Turner), the youngest and handsomest of Thorin’s followers. The attraction isn’t strong enough for the Dwarves to exploit directly, but it will come in handy once they escape by other means. That other means is Bilbo, who evaded capture by the Elves thanks to the ring of invisibility he stole from Gollum toward the end of An Unexpected Journey. (In a misguided attempt to “foreshadow” the ring’s demonic power, The Desolation of Smaug portrays this as the one occasion on which Bilbo is able to bear wearing it for any length of time.) When a celebration of some kind leaves three quarters of the Elves in the kingdom pants-pissing drunk— the dungeon warden included— Bilbo steals the keys to the cells and releases his companions. Then he floats them all out of Tharanduil’s castle in the empty wine barrels. In The Hobbit, the barrel escape was a case of guile and stealth winning out over force and numbers, but here in Hobbit X-Treme!, the Dwarves are found out not only by the Elves, but also by Azog and his Orcs, leading to by far the silliest fight scene of a movie bursting at the seams with very silly fight scenes. In the aftermath, Tauriel and Legolas both find themselves outside of Tharanduil’s locked-down fortress, tracking the Orcs with vengeance on their minds as the Orcs in turn track the Dwarves.

The latter’s salvation is a chance meeting with a human barge pilot named Bard (Luke Evans, from Clash of the Titans and The Raven). He operates out of Lake Town, a sort of pontoon city built by refugees from Dale after Smaug destroyed their original settlement. Lake Town subsists under the heavy boot of an authoritarian burgomaster (Stephen Fry, of Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy) who will not be pleased to see thirteen Dwarves and a Hobbit show up out of nowhere, but Balin (Ken Stott), the oldest and most level-headed of the company, persuades Bard to smuggle them in anyway. After all, they’re going to need rest, provisions, and most of all weapons if they’re to launch an attack on Erebor, and Lake Town, situated at the foot of the mountain, is the only sensible staging area for the final phase of the quest. Mind you, no one says anything at first about attacking Erebor. If what Bard says about the burgomaster is true— and it seems at the very least to be true of his chief flunky, Alfrid (Judge Dredd’s Ryan Gage)— then it’s probably safest to keep mum about their business for as long as possible. In the end, though, Lake Town’s kiddie-league Gestapo forces Thorin’s hand, leaving him to choose between revealing his aims and accepting another term of imprisonment. Thorin appeals both to the townspeople’s pride as sons and daughters of Dale and to their economic interests as the traders on whom a restored King Under the Mountain would naturally rely, but doing so causes a curious reversal. Suddenly the burgomaster is the Dwarves’ best friend, and Bard is the one trying to stop them. The pilot, not without cause, is highly skeptical of Thorin’s ability to do anything to the dragon save to piss him off, and Lake Town is obviously the first place on which Smaug will vent his fury. Bard, as it happens, is the smartest guy in the room on this occasion, although we’ll have to wait for the next film to see exactly how big a clusterfuck Bilbo and the Dwarves have set in motion.

You’ll notice that I said next to nothing about Bilbo Baggins in the whole foregoing synopsis. That’s because The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug gives approximately 0.45 fucks about its before-the-colon title character. That was a problem in An Unexpected Journey, too, but The Desolation of Smaug raises it to a new and completely inexcusable level. This is Thorin’s movie first and foremost, Gandalf’s to a lesser degree, and then Legolas and Tauriel’s. Poor Bilbo brings up the rear to such an extent that he finds himself contending with fucking Kili for the last meager scraps of Peter Jackson’s attention. What an egregious misstep that is comes through most clearly in the confrontation between Hobbit and dragon, which ought to be the decisive station in Bilbo’s Hero’s Journey. In the book (and, for that matter, in the Rankin-Bass cartoon adaptation from the 70’s), Bilbo has put together a pretty impressive resumé of derring-do by the time he sneaks into Smaug’s lair. He outwitted Gollum and made off with his magic ring; he evaded the Goblins to reunite with his comrades; he defeated the spiders of Mirkwood and singlehandedly stopped them from eating the Dwarves; he devised and executed a flawless escape from the Wood Elves’ dungeon. When Smaug wakes up and senses that he’s no longer alone under his mountain, Bilbo is halfway justified in being cocky. That’s the reason for the grandiloquent, riddling introduction he makes to the monster: “I come from under the hill, and under the hills and over the hills my paths led— and through the air. I am he that walks unseen… I am the clue-finder, the web-cutter, the stinging fly. I was chosen for the lucky number… I am he that buries his friends alive and drowns them and draws them alive again from the water. I came from the end of a bag, but no bag went over me… I am the friend of bears and the guest of eagles. I am Ringwinner and Luckwearer; I am Barrel-Rider.” Far from the stodgy, middle-class homebody whom Gandalf had to terrify into joining the expedition, Bilbo has grown into the sort of person who’ll shit-talk a dragon! But not here. Jackson’s Bilbo hasn’t enjoyed the triumphs that so strengthened Tolkien’s. Gollum’s ring is too frightening to wear because to do so puts Bilbo in touch with the mind of Sauron. The Dwarves did their own spider-slaying for the most part, and what help they had came from the Elves who later imprisoned them. The barrel escape was a farcical failure, salvaged only when the Orcs gave Tharanduil’s guards something more pressing to worry about. So of course Jackson’s Bilbo is still a coward when he faces Smaug, and the work of driving the dragon out into the daylight is done by Thorin and the Dwarves. From the look of things, the honor of identifying Smaug’s weakness is being reserved for some other character, too— Bard, most likely. I suppose a case could be made for the legitimacy of retelling this story in such Dwarf-, wizard-, and Elf-centric terms, but not if it’s still going to be called The Hobbit.

Besides, even if we were to accept an interpretation of The Hobbit in which Bilbo was an afterthought, The Desolation of Smaug would be a pretty piss-poor rendering of the concept. This is a movie that persistently insults its viewers’ intelligence, discernment, and powers of concentration. For all the effort it counterproductively expends on callbacks to The Lord of the Rings, it expects us to put not one moment’s thought into the implications of those connections. For instance, roughly 60 years are supposed to elapse between the events of this movie and the beginning of the earlier trilogy. Tell me, then: if Gandalf learns for certain this soon that the Necromancer is really Sauron, and he suspects that Bilbo has found the One Ring (which is the only plausible interpretation of a scene that falls shortly before Gandalf departs to go gallivanting around Middle Earth’s shittier neighborhoods with Radagast), then what imaginable justification can he have for not confiscating the Hobbit’s prize the moment they next meet, and sending it off under guard to Mount Doom for destruction while its rightful owner is still polishing his pecker in Dol Guldur? If all this trilogy’s rigmarole is warranted to keep Sauron from acquiring a dragon, then surely the One Goddamned Ring cannot be permitted to sit in a box on Bilbo’s mantelpiece for 60 fucking years until the Dark Lord is powerful enough to come looking for it! The only excuse for a delay of that magnitude is ignorance on Gandalf’s part, but Jackson has taken away the wizard’s plausible deniability.

Where The Desolation of Smaug becomes truly infuriating, though, is in its determination never to let fifteen minutes go by without a battle of some kind— and not infrequently a battle that lasts longer than the refractory period since the last one. These generally aren’t just any battles, either, but running, leaping, swinging, spinning, cartwheeling, somersaulting, white-water rafting battles in which no sector of the screen is without some object or participant in constant agitation. Jackson apparently will not be satisfied until every single last member of the audience has vertigo, motion sickness, or at the very least a screaming eye-strain headache, so that I’ve never been so thankful not to be watching a movie in 3-D Imax at 48 digital hi-def frames per second. Theaters screening that version should take a hint from the distributors of Mark of the Devil, and hand out free barf-bags with every ticket sold. What’s really galling is that Jackson has shown himself capable of directing overstuffed action in the past. The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King was practically one continuous clash of armies whenever Frodo and Sam weren’t around, but that movie earned its hectic tenor. For one thing, it was the final installment in its trilogy, and the culmination of an apocalyptic struggle. But beyond that, there were meaningful character moments secreted throughout the din, as the siege of Gondor gave everyone involved in it a chance to shine and to reveal their best nature. That’s not what happens here. In this movie, it’s often difficult to tell who’s even taking part in any given skirmish, since everybody but Bilbo basically disappears into an undifferentiated mass of flowing and/or unkempt hair. And when we can tell who we’re looking at, there’s usually no real tension, because we already know that they have to survive to play their roles in The Lord of the Rings. Legolas gets the most egregious moment of fraudulent pseudo-suspense during the melee surrounding the barrel escape, when an Orc draws down on him from behind only to be slaughtered spectacularly by Tauriel; it’s the accompanying musical cue, I think, that makes the scene so offensive, droning ominously in some minor interval as if there were any question that some ill might possibly befall the Elf-prince. The result resembles not the siege of Gondor but the dinosaur stampede in King Kong— or, when Legolas and Tauriel are in the spotlight, that movie’s ridiculous trapeze fight between Kong and the theropods. And The Desolation of Smaug goes on in that vein with only the briefest interruptions for over two and a half hours. I’ve never seen a 160-minute film display so little faith in its audience’s attention span.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact