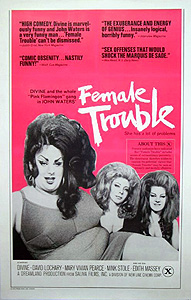

Female Trouble (1974) -***½

Female Trouble (1974) -***½

There has never, so far as I know, been another filmmaker quite like John Waters. That may sound like a bit of a stretch to those who know him only from his post-mainstream success career, but you people who have only seen Hairspray, Cry Baby, Pecker, or even Serial Mom don’t know the half of it. Sure, those later movies reflect a distinctly fucked-up sensibility, but for the most part, they are merely harmlessly eccentric. Waters’s films from the 1970’s are another matter altogether. For one thing, the movies Waters has made since the late 80’s all use real— if usually minor— actors for most of the roles, and their production values are more or less commensurate with what we usually expect from independent and minor-studio Hollywood filmmaking, even if Waters generally stays way the hell away from Hollywood in the geographical sense of the term. His early movies, on the other hand, are cheap in ways that even many B-movie fans have never seen before (1972’s Pink Flamingos had a budget of something like $16,000), and their casts are made up of a repertory company of Waters’s friends, whose main qualification for their roles was their unwavering willingness to do absolutely any fucked-up, revolting thing the director asked. We’re talking here about a director whose favorite leading man was a junkie with whom he had gone to high school, and whose favorite leading lady was, in fact, a 300-pound transvestite. Female Trouble was the last of the movies Waters made with this circle of intimates before burnout, drug overdoses, and the sad fact of growing up began to take their tolls, and it makes for a fitting end to this era. And as a small indicator of the kind of antisocial lunacy we’re dealing with here, consider that Female Trouble is prominently dedicated to Manson family murderer Charles “Tex” Watson. Tell me truthfully— do you think the John Waters of today would dedicate a movie to Jeffrey Dahmer? No, I don’t think so either.

The dedication makes perfect sense, though, in this context. Female Trouble details the criminal career of Dawn Davenport (Divine, of course), from her early days as a juvenile delinquent to her final apprehension by the forces of law and order, and subsequent death in the electric chair. And because this is a John Waters movie, it all begins with a pair of cha-cha heels. The shoes in question are the only thing teenaged Dawn really wants for Christmas in 1960, and as she tells her friends, Concetta (Cookie Mueller) and Chicklette (Susan Walsh, a peripheral member of the Waters team, who had played similar small roles in Mondo Trasho, Multiple Maniacs, and Pink Flamingos), her parents had better get them for her. They don’t, of course, and the ensuing fight ends with Dawn running away from home, Mrs. Davenport lying pinned beneath the fallen Christmas tree, and Mr. Davenport shaking his fist at his fleeing daughter, warning her that he’s going to have her sent to reform school. On the road away from her parents’ place, Dawn is picked up by a man named Earl Peterson (Divine again, in a rare non-drag appearance), who soon pulls the car over and has sex with Dawn in the woods. (The sight of Divine in drag being fucked by Divine out of drag [with a little help from a body double whose resemblance to Divine stops at a similarity of bulk] is truly a wonder to behold.) Dawn naturally gets pregnant as a result of this encounter, and gives birth to her daughter, Taffy, in a filthy room at the Albion hotel. (Divine’s severing the umbilical cord with her teeth is a nice touch.)

Over the course of the next seven years, Dawn bounces through a number of jobs— waitressing at the Little Tavern, dancing at the Red Garter strip club, whoring with Concetta and Chicklette— before finding her true calling in petty larceny. She begins by mugging the homeless, and gradually works her way up to burglarizing houses in downtown Baltimore with her two friends. Meanwhile, Taffy has grown into a seven-year-old every bit as obnoxious as one suspects her mother had been. (Since Dawn’s idea of parenting extends no farther than locking Taffy in the closet and beating her with an automobile radio antenna, this is scarcely surprising.) Then one day in 1967, Concetta and Chicklette make the fateful suggestion that Dawn combat the misery of her life by getting her hair done at Le Lipstick, a salon so exclusive that prospective customers have to audition in order to get in.

Le Lipstick is owned by Donald and Donna Dasher (David Lochary and Mary Vivian Pierce, the former of whom would soon die of a PCP overdose). When asked if any of the day’s crop of would-be customers is “particularly appalling,” their secretary mentions Dawn Davenport specifically— “I think you’ll like her; she seems especially cheap.” And so they do, even more so after Dawn gives her occupation as “thief and shit-kicker,” and mentions, for no particular reason, that she wants to be famous. The Dashers think Dawn is exactly the sort of person they want their salon associated with, and she is duly admitted into its hallowed confines.

You wouldn’t think getting your hair done could change your life, but then, you and I don’t live in a John Waters movie. One of Le Lipstick’s hairdressers, Gator Nelson (Michael Potter, who the Internet Movie Database used to claim appeared four years later in the infamous Star Wars Holiday Special, although I somehow doubt that), catches Dawn’s eye, and the two soon fall in love. In one sense, this is awfully convenient, because Gator lives right next door to Dawn, in the home of his crazy old Aunt Ida (the unforgettable Edith Massey, in one of her most notorious roles). Then again, Aunt Ida does not approve of Gator’s budding romance with the girl next door, for reasons that are made clear by the following exchange of dialogue:

| Ida: | Have you met any nice boys in the salon? |

| Gator: | They’re all pretty nice. |

| Ida: | I mean any nice queer boys— do you fool with any of them? |

| Gator: | Aunt Ida, you know I dig women. |

| Ida: | Oh, don’t tell me that... |

| Gator: | Christ, let’s not go through this again... |

| Ida: | All those beauticians, and you don’t have any boy dates? |

| Gator: | I don’t want any boy dates! |

| Ida: | Oh, honey, I’d be so happy if you turned nellie... |

| Gator: | Ain’t no way; I’m straight. I like a lot of queers, but I don’t dig their equipment, you know? I like women! |

| Ida: | But you could change! Queers are just better. I’d be so happy if you was a fag, and had a nice beautician boyfriend... I’d never have to worry. |

| Gator: | There ain’t nothing to worry about. |

| Ida: | I worry that you’ll work in an office! Have children! Celebrate wedding anniversaries! The world of heterosexual is a sick and boring life! |

So you can imagine how well it goes over with Aunt Ida when Gator and Dawn get married the following year. Within days, Ida is using Dawn and Gator’s back yard as a dumping ground for her trash, and Dawn is bombing Ida with dead fish from her second-story window whenever the older woman walks by.

But even worse portents for the future of the marriage come from within the couple’s own home in the years to come. Taffy (who has now grown into Mink Stole) is even nastier as a pre-teen than she was as a little kid, and she fights with Gator continually. Gator’s fruitless efforts to get his stepdaughter to have sex with him (“I wouldn’t suck your lousy dick if I were suffocating, and there was oxygen in your balls!!!!”) oddly seem not to trouble Dawn in and of themselves, but the constant shouting match between the other two members of her family really gets on her nerves. Matters degenerate further when Gator starts cheating on Dawn, but it isn’t until the hairdresser starts taunting his porcine wife by sticking food in her mouth when they’re having sex that Dawn finally draws the line, and throws Gator out of the house.

Not only that, she begins divorce proceedings against Gator, and even manages to get him fired from Le Lipstick. The opportunity for the latter dirty trick arises when the Dashers call Dawn into their office to extend to her an interesting proposition. They want Dawn to collaborate with them on a “beauty experiment.” This will entail Dawn allowing herself to be photographed while committing certain crimes— it is the Dashers’ theory that crime increases one’s beauty exponentially, and they think Dawn has what it takes to help them prove it. Dawn jumps at this chance to achieve her lifelong ambitions of fame (hey, if crime could make Manson, Speck, Gacy, and Gein household names, why not Dawn Davenport too?), and then capitalizes on her benefactors’ newly developed willingness to do favors for her to cut Gator out of her life completely.

Gator, of course, takes it pretty badly, and he runs off to Detroit to build a new life in the auto industry (accent on second syllable in Gator’s pronunciation). Aunt Ida, incensed at Dawn’s final success in taking her nephew away from her, barges into Dawn’s house in the middle of a visit from the Dashers, and douses Dawn’s face with acid. Now, in the world you and I inhabit, this would be a major tragedy, but not on Planet Waters. The Dashers and their circle convince Dawn that the massive scarring of her face (she now looks like a fatter and hypothetically female version of Claude Rains in the 1943 remake of The Phantom of the Opera) has made her even more beautiful, and added immeasurably to her star power. From this point on, Dawn will evolve simultaneously into an ever more striking embodiment of anti-glamour, and an ever more vicious and wanton criminal. The process climaxes in the Dasher-produced Dawn Davenport “nightclub act,” which mainly consists of Dawn doing trampoline stunts and rubbing herself with dead fish before she opens fire on her audience with a revolver in a sequence which would later be ripped off by the makers of The Great Rock and Roll Swindle. The law now takes notice of Dawn at last, and she is apprehended, tried, convicted, and sentenced to die in the chair. Dawn goes to her death with the triumphant joy one usually expects from academy award winners, even going so far as to give a sort of acceptance speech while the prison guards strap her in and attach the electrodes to her head and extremities.

Female Trouble makes for an excellent introduction to the young John Waters, in that it isn’t so stunningly and unrelentingly grotesque as, say, Pink Flamingos, but is still confrontationally disgusting in a way that nothing the director has made in the past 20 years even approaches. It also comes as close as the irony-obsessed Waters ever will to offering an explicit manifesto for his twisted artistic vision. The Dashers’ “Crime is Beauty” formula could easily be made to stand in for the “Squalor is Beauty” esthetic that informs all of Waters’s work to a greater or lesser degree. The exaltation of the ugly and the wretched can still be seen in his movies today, even if it isn’t treated with the same kind of obsessive stridency as it is in Female Trouble and its predecessors. This movie also features a much higher quota of the sort of random craziness for which Waters is justly renowned, but which only occasionally surfaces in his more recent films. Not only are such major plot developments as Dawn’s marriage to Gator exploited for their potential shock value (get a load of Dawn’s wedding dress), there are any number of digressions from the main story that are included solely because of the opportunities they introduce for further wallowing in squalor and bad taste. There’s no real reason why Taffy should become a Hare Krishna in the final act, nor is any narrative purpose served by the subplot in which Taffy tracks down her father and finds him to be just as much of a pig as Dawn always said he was. But the Krishna twist lets Waters echo and one-up a scene from early in the film in which Taffy’s jump-rope chants drive Dawn to tie the girl to her bed, and Earl Peterson’s reappearance provides an excuse for a Herschell Gordon Lewis-style gore scene. And for what it’s worth, Female Trouble is also almost certainly the all-time cinematic champion when it comes to putting the morbidly obese into preposterously revealing outfits— Aunt Ida’s leather catsuit in particular is going to give a lot of people nightmares.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact