Mondo Trasho (1969) -**½

Mondo Trasho (1969) -**½

We can’t, as a practical matter, go back to the very beginning of John Waters’s filmmaking career. His three earliest movies, the short subjects Hag in a Black Leather Jacket, Roman Candles, and Eat Your Makeup, have never been released on home video even in bootleg form, nor have they been exhibited publicly since their “theatrical runs” in the mid-to-late 1960’s. There’s nothing very unusual about that in and of itself. Most artists have a body of juvenilia which they keep safely out of sight once they’ve reached a certain level of creative maturity— stuffing it “in my closet, where it belongs,” as Waters himself says of Hag in a Black Leather Jacket. The Waters juvenilia are a bit of a special case, however, for their creator has seen to it that they maintain an atypically high profile even despite their unavailability. In his rather premature 1981 memoir, Shock Value, Baltimore’s favorite cinematic son devoted about half of the longest chapter to the story of making, exhibiting, and shilling for these early, experimental films. Especially in the case of Eat Your Makeup, it would not be going too far to say that the Shock Value chapter ballyhoos them. Furthermore, all three shorts screened before a paying public as attractions in their own right when they were new (as opposed to playing as part of a festival program or in support of some more prestigious feature), although it’s open to debate whether presentation in coffee houses and rented church halls in Baltimore and Provincetown, Massachusetts, qualifies as commercial exhibition. In any event, Waters did manage to recoup the trifling amounts of money he spent to make them. The result of this ambivalent treatment is that Waters has skillfully engineered a demand for movies which he has no intention of ever putting back in the public eye, and I have no doubt that his death will be followed in short order by all of that primitive material sneaking out onto bootleg versions of whatever the default home video format is circa 2030.

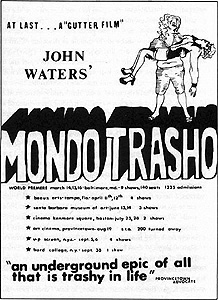

In the meantime, what we can do is to revisit the moment of transition between Waters essentially making movies on a lark with his reprobate friends and the Dreamland Studios team (as they called themselves) becoming serious about building careers in cinema on their own eccentric terms. That transition came with Mondo Trasho, Waters’s first feature-length film, and his first to receive any approximation of professional distribution. Mondo Trasho premiered, as usual, with a nine-showing engagement at the Emmanuel Church rental hall, but it was quickly picked up by the New York-based Film-Makers Cooperative as part of their fledgling effort to break into the distro business. The coop never managed to secure a booking in their home city, ironically enough, but they did send Mondo Trasho to Los Angeles. There it received a surprising amount of attention, getting reviewed by Variety, Show, and the Los Angeles Free Press. Andy Warhol’s Interview ran the official press release even though it was impossible to see the film on that magazine’s home turf. And Pauline Kael, of all people, namedropped Mondo Trasho in her New Yorker review of Federico Fellini’s Satyricon, of all places. Mondo Trasho had longer legs than the shorts, too. It was resurrected to serve as a supporting feature for Waters’s next film, Multiple Maniacs, and although the totally unlicensed score taken from its creator’s own record collection threatens to keep it permanently out of circulation on DVD, it was available in VHS release as recently as 1998. So while seeing Roman Candles would seem to require personally sweet-talking Waters into showing it to you, Mondo Trasho requires merely that you be format-flexible and know where to look.

The titles and credits are preceded by a few minutes of a man dressed as a Medieval executioner beheading chickens with a hatchet beside a tiny stream. Even by the extremely loose standards of an early John Waters movie, this has nothing to do with anything. The real action begins when a striking, leggy blonde girl (Mary Vivian Pearce, whom Waters has known since childhood, and whom he has cast in every one of his movies going all the way back to Hag in a Black Leather Jacket) goes out for a walk in the park. (Incidentally, given the monomaniacal exaltation of ugliness that has characterized seemingly all of Waters’s work, it’s really astonishing how gorgeous Pearce is in this picture.) Taking a seat on one of the benches, she begins throwing raw hamburger to the ants, beetles, and cockroaches, much as people outside of John Waters movies might throw stale bread to ducks or pigeons. Her attention thus focused on the insects, the blonde fails to notice a long-haired pervert (John Leisenring) creeping through the trees and underbrush behind her. Not to worry, though— this foot-fetishist is much more benign than the one in Polyester, and the blonde is happy to follow him back into the woods to have her feet orally pleasured. (And suddenly it dawns on me where I must have gotten it into my head that a woman might appreciate such a thing…) This, apparently, is something the blonde girl has dreamed of for some time, for while the pervert fellates her toes, she ecstatically envisions herself as Cinderella, delivered from the clutches of her evil stepsisters by a hairy, foot-worshipping prince.

Meanwhile, Divine (the cross-dressing Glenn Milstead, stepping for the first time into the leading lady spot recently vacated by the death of Waters’s original avatar of anti-glamour, Maelcum Soul) is driving around the Johns Hopkins University campus in her 1959 Cadillac convertible. At the same moment that the blonde’s dreams of future oro-pedal bliss are being shattered by the pervert slinking off like a thief in the night after shrimping her to orgasm, Divine catches sight of a handsome male hitchhiker (Mark Isherwood). Undressing the hitchhiker with her eyes (an effect achieved by stripping Isherwood in stop-substitution— which briefly landed several of the crew in jail when a policeman stumbled upon the shoot), Divine has no attention to spare for the blonde girl dejectedly scaling the roadside embankment from the woods. She accidentally runs the blonde down while making her final approach to where the hitchhiker stands.

Now in most subsequent John Waters movies, you’d expect Divine’s character to grab the hitchhiker and race off— possibly after driving over Mary Vivian Pearce a couple more times, just to be sure. This Divine is a rather more compassionate soul, however, and she spends the rest of the movie trying to get the blonde patched up. The first thing the stricken girl needs, obviously, is a new outfit to replace the torn and grit-streaked clothes she’s currently wearing, so Divine procures one by shoplifting a lacy, black dress from a junk shop and robbing a passed-out wino of her incongruously sexy shoes. Then she takes her inadvertent victim to a laundromat to get her changed into the new duds. While Divine is busy wrestling the blonde out of her shorts, the Virgin Mary (Margie Skidmore) appears in the laundromat, and the soundtrack of pilfered pop songs is interrupted by a tacky hymn for choir and organ. (One assumes that came from Waters’s parents’ record collection.) Divine falls to her knees in histrionic prayer, begging for both aid in combating the pernicious influence of Original Sin and the miraculous healing of the blonde. Mary somewhat unhelpfully summons an angel with a wheelchair (Lizzy Temple Black), then the two celestial personages zap back to Heaven whence they came.

The wheelchair does at least make it easier for Divine to trundle the blonde around— which is a matter of some importance, given that she returns to her car just in time to watch it being stolen. I guess there’s no second-guessing divine (small-l) benevolence after all. The next thing Divine knows, she’s being accosted by an escaped lunatic, but before that encounter can go very far, a station wagon full of asylum orderlies pulls up, and the men with the butterfly nets (literally in this case) recapture the roving psycho. Then they snag Divine and the blonde, too. The asylum turns out to be little more than a big, sparsely furnished room where the inmates wander unrestrained and are kept entertained by a topless dancer (Mink Stole) apparently recruited from among them. Again the Virgin Mary intercedes, and this time her aid is more obviously efficacious. She still doesn’t lay on hands to heal the blonde (although she does miracle up a mink coat for her and a holy switchblade for Divine), but blowing the front door off the asylum neatly solves the unjust confinement problem.

At this point, Divine finally does what seems like the sensible thing, and arranges for the blonde girl to see a doctor. Unfortunately, Dr. Coathanger (David Lochary) happens to be a mad doctor (to say nothing of his heroin addiction), and in the process of treating the blonde’s injuries, he also performs a hideous medical experiment on her, sawing off her lovely feet to replace them with rubbery ones fit for some manner of monster. Meanwhile, out in the waiting room, police and tabloid journalists investigating Divine’s shoplifting, asylum-breaking, hitting-and-running, and so forth have traced her to the doctor’s office, and the ensuing confrontation swiftly devolves into a free-for-all shootout involving cops, reporters, patients, and Dr. Coathanger’s administrative staff. Mary’s holy switchblade apparently renders Divine impervious to bullets while she’s holding it, but the straight razor wielded by one of the other patients is a different matter for some reason. Badly wounded, Divine bursts into the operating theater just after the blonde regains consciousness, and the two of them join Dr. Coathanger, his nurse (Berenica Cipcus), and his secretary (Pat Moran) in escaping out the window. Divine and the blonde get separated from the others soon thereafter, winding up on a farm— where Divine bleeds to death in a pigsty, but is lifted up to Heaven by her old pal, Mary. Finally, the blonde discovers that her transplanted monster feet have given her powers of teleportation, and that she can zap herself home by knocking her heels together like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz. All she needs is a little practice.

Earlier in this review, I called Mondo Trasho a transitional movie, and like most works of an artist in transition, it displays features of both the period that is ending and the one that is about to begin. With its grown-up-movie length, its starring role for Divine, and its halfway-serious attempts to impose a unified narrative framework on what must surely have occurred to Waters first as a succession of unconnected set-pieces, it is unmistakably paving the way for the films that would establish Waters’s reputation in the 1970’s. In Mondo Trasho, one can plainly see the sensibility of Dreamland Studios’ classical era taking shape. That said, though, I find Mondo Trasho more interesting for its holdover aspects, for the hints that it gives of the unseen John Waters.

The point that emerges most sharply in Waters’s writing about the dawn of his career is that he spent the 1960’s thinking of himself as a maker of underground experimental art films. He had little interest in the theory or technique of visual storytelling, and still less in emulating the style of respectable Hollywood. What he cared about was provoking a specific mental or emotional response from the viewer, and he was content to grope his way toward it on instinct. He was also something of a formal deconstructionist, a tendency best illustrated by Roman Candles. Although I keep calling Roman Candles a short film, it actually contained over 100 minutes of footage— but since it was meant to be shown on three projectors simultaneously, it ran closer to 40 minutes in practice. The audio component was even more idiosyncratic, consisting of a taped sound collage assembled from rock and roll songs, radio advertisements, and samples from a press conference given by Lee Harvey Oswald’s mother. Obviously narrative coherence in the conventional sense was not even a trivial concern there, and if we may judge from Waters’s own descriptions, none of his earliest movies had any logic driving their “plots” save that of deliberate incongruity and conscientiously exaggerated bad taste. In that sense, the young John Waters was on the same page as the Warhol circle up in New York, and it isn’t impossible to imagine him making something like Flesh for Frankenstein had he been in a position to attract Hairspray-scale financial backing ten or fifteen years earlier. There was, however, a major difference between Waters and, say, Paul Morrissey, in that Waters generally had no place in his work for a political perspective as such, and he was ultimately just as hostile toward the “mainstream” counterculture of the late 60’s and early 70’s as he was toward the genuine mainstream.

A lot of that Warholian approach is visible in Mondo Trasho— and so, if one looks closely enough, is a rather un-Waters-like concentration on lambasting just one of the most typical of all the normative counterculture’s bugaboos. Although I stand by my statement that Mondo Trasho displays a linearity apparently without precedent in its creator’s prior work, it’s still an obvious case of connect-the-dots writing, with a through-line improvised to justify preconceived incidents rather than incidents devised to serve the needs of a preconceived plot. And even then, a fair amount of what happens in Mondo Trasho is simply not on the main Point A-to-Point Z pathway at all. Those parts of the movie that focus on Mary Vivian Pearce are pure sleaze surrealism, connected to the Divine-centric “A-plot” only by the circumstances of the two characters’ meeting. For most of the running time, Pearce is for all practical purposes an inanimate object that Divine must carry from place to place, without any independent agency of her own, and a version of Mondo Trasho that jumped directly from the car accident to the women’s arrival at Dr. Coathanger’s office would make just as much sense as the one we actually have. And of course there’s that mass chicken execution before the credits, which is nothing but free-floating vileness for its own sake. Divine’s part of the movie, in contrast, only appears to be incoherent, random craziness. Take a close look at what happens during Mondo Trasho’s central hour. Divine enters the story as an embodiment of lust (naked hitchhiker), greed (shoplifting), and gluttony (just look at her), and the first thing she does is to nearly kill somebody through her sin-directed carelessness. But as soon as she takes it upon herself to help Mary Vivian Pearce (turning her back on the hitchhiker who had her so heated up while she’s at it), she earns the favor of the Virgin Mary, who intervenes twice on her behalf while she seeks aid for the victim of her negligence. And by refusing to flee the firefight in Dr. Coathanger’s waiting room without Pearce, Divine finally makes the ultimate sacrifice in her efforts to put things right— at which point she ascends bodily into Heaven like a trailer-trash saint. Divine’s story, in other words, is a crass parody of the redemption-and-martyrdom narratives so beloved of the Roman Catholic Church in which Waters was raised and educated. Now a vein of reaction against his Catholic upbringing runs through practically the whole Waters canon, but I know of no other film in his repertoire (except possibly Roman Candles, on which the jury must be reckoned out, given its continued unavailability) that places such intense and continuous focus on Catholic themes. It came as quite a shock when I realized that, for Mondo Trasho looks on its face like the least focused John Waters feature.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact