Multiple Maniacs (1970) -***

Multiple Maniacs (1970) -***

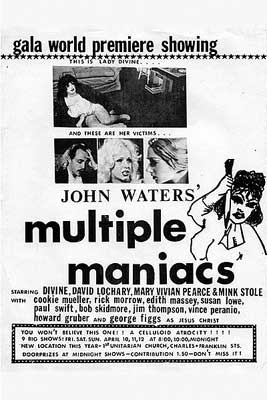

You know you’re dealing with a truly peculiar filmmaker when you can point to something like Multiple Maniacs and identify it with a straight face as their first normal movie. It’s true, though. Multiple Maniacs has dialogue. It had a script, even if much of that script had to be abandoned while the film was in mid-production due to unforeseen events on the opposite side of the continent. It plays on a single screen all the way through, and runs a little less than an hour and a half. Those are not things you can necessarily say about the earliest of the movies made by writer/director/producer/etc. John Waters, during the period when his Dreamland Studios was basically Baltimore’s urban white trash answer to the Warhol Factory. The typical Dreamland production in those formative days was an amorphous formal experiment bearing no meaningful resemblance to even the most out-there commercial cinema, its options for exhibition limited to community center rental halls and the like (Baltimore in the late 60’s not being well served by venues catering to the modern art scene). Even Mondo Trasho enjoyed only the scantiest approximation of professional distribution in its initial run. Multiple Maniacs, on the other hand, played in actual theaters from the beginning— small theaters, strange theaters, and struggling theaters, to be sure, but theaters nonetheless. Still, let’s not make too much of Multiple Maniacs’ formal normality. By any other standard, this is a bizarre film indeed, showing that Waters completed the first big transition of his career with without losing a bit of his mad, manic edge. Indeed, he’d only just begun to develop the trash-radical sensibility for which he is now justly infamous, and this movie’s first-run audiences hadn’t seen anything yet.

Multiple Maniacs may have a script, but it only just barely has a plot. In a suburban Baltimore park somewhere (actually Waters’s parents’ expansive front yard), an outlandishly attired carnival barker (the original Dreamland leading man, David Lochary) touts the attractions of Lady Divine’s Cavalcade of Perversions. SEE!— the pornographer and his model, flouting all shame and decency! SEE!— the heroin addict jonesing for his next fix! SEE!—actual queers, kissing like lovers on the lips! The Cavalcade of Perversions has panty-sniffers, armpit-lickers, and puke-eaters! It has crudity, nudity, and lewdity! And as its ultimate attraction, it has Lady Divine herself (Divine, obviously), a person so vile, with proclivities so shocking, that Mr. David is forbidden even to describe what goes on within the confines of her private tent! In fact, though, the whole Cavalcade is a scam. Not that Lady Divine doesn’t employ a veritable menagerie of top-shelf deviants, but the climax to the show is merely a setup for the mass mugging of the audience. Once inside the mistress’s tent, the punters have nets thrown over them, and are relieved of all their valuables at gunpoint— and Lady Divine has a very itchy trigger finger!

The Cavalcade of Perversions is not at all the happy family of degenerates that Divine would lead subsequently in Pink Flamingos, however. This version of Divine is instead a paranoid tyrant who fantasizes about cutting all her followers loose to go on an epic, solo, worldwide murder binge. Her romance with Mr. David has been drained of all its passion, and is now kept alive solely by her frequent reminders that she knows the truth about what he got up to during a drug blackout while they were living in Los Angeles last year. Specifically on August 9th, the night when somebody (hint, hint) invaded Roman Polanski’s house and disassembled Sharon Tate and three of her friends. If Mr. David ever leaves her, Lady Divine is sure she could find a detective or two back in LA who would find her reminiscence interesting. Mr. David has been seeking comfort in the arms of a girl named Bonnie (Mary Vivienne Pearce, the human MacGuffin of Mondo Trasho), and even attempts to get her a job with the Cavalcade as a coprophagic gerontophiliac so that they can more easily spend time together. (Blissfully, Bonnie’s audition never proceeds far enough to require a demonstration.) But both adulterers know that Lady Divine is going to find them out sooner or later. There’ll be just one way out of that fix when it arises, and Bonnie therefore urges Mr. David to let her kill Divine before she decides to kill them.

Actually, it may already be too late for that. The lovers make their plans in a rented room at a flophouse called Pete’s Hotel, and the barmaid there (Edith Massie, effectively playing herself) is a spy for Lady Divine. Edith calls Divine to snitch on Mr. David’s dalliance (she doesn’t hear him and Bonnie discussing their murder plot), and the news sends her into a rage. Leaving her constantly topless prostitute daughter, Cookie (Cookie Mueller), alone in the apartment with her latest trick— a Weatherman by the name of Steve (Paul Swift, a lesser-known Dreamlander who nevertheless stuck around long enough to appear in both Pink Flamingos and Desperate Living)— Lady Divine storms off to Pete’s with violence on her mind. (Note that Dreamland Baltimore is a screwy enough place that it took a few extra lines of dialogue for me to feel certain that Steve was meant to be a hippie terrorist, and not a meteorologist.)

Bonnie and Mr. David are in luck, however, for Divine gets repeatedly sidetracked on her way to the hotel. First, she gets waylaid, mugged, and raped in an alley by two of her own sideshow freaks, high from sniffing glue and perhaps on a mission from the scheming barker himself. Afterward, she receives a visitation from the Infant of Prague (Michael Renner Jr.), who takes her hand and leads her to the Church of St. Cecilia. Lady Divine reasonably interprets this holy intervention to signify that God has blessed her plans to kill Mr. David and Bonnie. Once at the church, she is converted to lesbianism by Mink the Religious Whore (Mink Stole), who accosts her in mid-prayer and diddles her with a rosary while chanting a meditation litany on the Stations of the Cross. So spiritually potent is Mink’s rosary job that it causes Divine to experience visions of Jesus Christ (George Figgs) feeding the 5000, getting betrayed by Judas, and undergoing the death march to Golgotha. When Mink learns that Lady Divine was on her way to murder her boyfriend before the Infant of Prague detoured her to St. Cecilia, she begs to be brought along. All her life, Mink has wanted nothing more than to perform the Sacrament of Extreme Unction on somebody, and what better opportunity is she going to get than this? Divine says that’s fine with her.

Meanwhile, Mr. David and Bonnie are seeing their own murder plans go rather awry. Divine is at Pete’s looking for them when they arrive at the apartment looking for her, and a flustered Bonnie winds up shooting Cookie and another Cavalcader called Ricky (Rick Morrow). They get the bodies hidden just in time to reset the scene for their ambush, but they’re not expecting Divine to be gunning for them as well. Unsurprisingly, Lady Divine comes out on top in the ensuing bloodbath. The trouble is, she kills Mink, too, in her mania, and she takes it poorly once she realizes the full ramifications of what she’s done. She takes it even worse when she gets raped again a moment later— this time by a nine-foot lobster that appears out of nowhere, and vanishes with just as little justification as soon as the deed is finished. Now irrevocably insane, Divine launches a rampage of indiscriminate terror all across Baltimore, until the National Guard is called out to destroy her.

I’m unclear on just what sort of ending John Waters originally envisioned for Multiple Maniacs, before the capture of the Manson Family put paid to any notion of the Cavalcade of Perversions taking credit for the Tate-La Bianca murders. But from the utter non-sequitur of the actual third act, I can only assume that the initial plan was scrapped in its entirety. I have to respect the purity of that, honestly. Real life renders the whole last act of your movie obsolete before it’s even been shot? Fuck it— GIANT RAPE LOBSTER! And then they end it as a 1950’s Moseying Monster flick, too. Say what you want, but you’re never going to forget that once you see it.

Otherwise, Multiple Maniacs is apt to strike today’s viewer as the less satisfactory prototype of Pink Flamingos. Both movies put Divine at the head of a tribe of criminal reprobates operating below the radar of straight society, but the love triangle conflict of Multiple Maniacs can’t help but seem pedestrian in comparison with its successor’s ever-escalating dispute over the title of Filthiest People Alive. On the other hand, this movie does offer the ultimate imaginable iteration of the blasphemy theme that runs through most if not all of Waters’s earliest work. Incredibly, the rosary job scene was filmed in a real church, the pastor of which was known to sympathize with New Left radicalism. He agreed to allow the shoot without even asking what the movie was about, and one of Waters’s friends kept him distracted in his office talking politics while the cast and crew did their work. Truly guerilla filmmaking at its finest. Lobstora is also a surprisingly effective puppet, even if some of the hardware holding it together is conspicuously visible. I suspect that the black and white film stock helped somewhat there, muting what was no doubt a cheesy, fire engine red paintjob into something at least faintly lifelike. And speaking of film stock, it’s worth pointing out that Multiple Maniacs is not merely monochrome, but orthochromatic as well. That’s why it has the appearance of an early silent movie, with everyone’s skin practically glowing a pasty, sickly white. Given Waters’s obsession with ugliness and disease, it’s only fitting, really, that the movie should look that way. So although Multiple Maniacs shows Waters with some growing yet to do and some kinks yet to work out (or perhaps to work in…), it’s well worth watching, both on the merits and to illustrate a stage in his evolution as a filmmaker.

We’re doing cheap movies this month at the B-Masters Cabal. I know what you’re thinking: “So what? You guys always do cheap movies.” But when we say “cheap” this time, we mean cheap! Like, “How can you even attempt to make a releasable film on this kind of money?” cheap. Multiple Maniacs set John Waters back about $5000, for example. Click the banner below to read of my colleagues’ adventures on the outermost fringes of cinematic poverty:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact