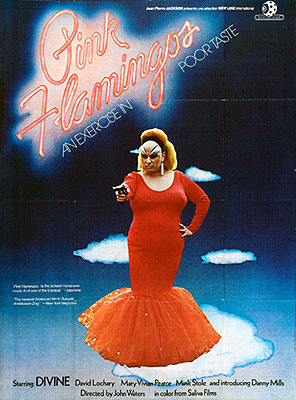

Pink Flamingos (1972) -*****

Pink Flamingos (1972) -*****

The world was not ready for Pink Flamingos in 1972. It still isn’t, which is a hell of an achievement, when you think about it. In the 47 years since this movie first wriggled out of its stained yet frilly drawers to drop a tarry deuce on the nation’s midnight movie screens, writer-director John Waters has transformed from the City of Baltimore’s greatest human embarrassment into its high-camp cultural ambassador. The films Waters made both immediately before and immediately after Pink Flamingos— Multiple Maniacs and Female Trouble— have received prestigious home video releases via the Criterion Collection. Hairspray, the first picture of Waters’s housebroken period, has been turned into a Broadway musical, and the musical has been translated back into celluloid with John Travolta in the role originated by longtime Waters muse Divine. Pink Flamingos itself has been shown at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, for heaven’s sake! By all the usual rules for such things, you’d expect Pink Flamingos to have become as quaint as other formerly shocking movies like And God Created Woman and Candy. Instead, however, it belongs to the same very exclusive club as Freaks. No matter how much time has passed, and for all its creator’s rehabilitation and admission into polite society, Pink Flamingos remains as impossibly repulsive as it ever was.

This is the story of a very unusual feud. On one side— the protagonist’s side, I hasten to emphasize— is a family of infamous criminals consisting of the fearsome Divine (Divine, obviously); her voyeuristic and neurotically touch-averse traveling companion, Cotton (Mary Vivian Pearce); her vaguely Mansonesque son, Crackers (Danny Mills); and her elderly and insane mother, Edie (Edith Massey), who spends all her time lounging in a playpen in her underwear (the same underwear that Carroll Baker wears in the notorious ad art for Baby Doll, no less!), gobbling down eggs. It’s never explained just how Divine and her family came by their notoriety, but the national tabloid press has dubbed them “the Filthiest People Alive,” so it must have been pretty extraordinary. We also know that their latest shenanigans, whatever they were, drew enough heat that they now feel compelled to lie low for a while. The family has settled in a dilapidated trailer outside of Baltimore, with Divine posing behind the strangely fitting pseudonym, “Babs Johnson.”

Opposing the Divine family are a couple by the names of Connie and Raymond Marble (Mink Stole and David Lochary). One might naturally assume that the Marbles are some of Divine’s erstwhile victims out for revenge, but that’s entirely too ordinary for Pink Flamingos. Rather, it seems that they have been avidly following Divine’s exploits via the tabloids, and they’re incensed that the gutter press has crowned her family— and not the Marbles— the Filthiest People Alive. I must admit that Connie and Raymond make a strong case for themselves. She’s an entrepreneur of sorts. With the help of her husband and their servant, Channing (Channing Wilroy), she kidnaps female hitchhikers and chains them up in the basement of their deceptively gracious-looking house. The girls are then impregnated by Channing so that Connie can sell the resulting babies to lesbian couples. (Also, I think we’re supposed to take it that Channing is gay himself, because he constantly expresses his disgust at having to fuck the Marbles’ captives. At the very least he’s a transvestite, as Connie will later catch him dressing up in her clothes.) A cut of the money raised thereby is then reinvested in porn-vending, drug-dealing, and various comparable pursuits. As for Raymond, there’s no sign that he does any work at all. Instead, he spends his days roaming Baltimore’s parks and recreational spaces, exposing himself to women with various meat byproducts (sausages, turkey necks, etc.) tied to his pecker. The Marbles dress hideously, engage in perverted sex practices, dye their hair garishly unnatural colors (note that this was several years before the emergence of punk as a distinct counterculture), and decorate their home to a standard of poor taste comparable with that on display in Divine’s trailer despite their implicitly much higher class status. So again— pretty filthy. And now that Divine and her family have returned to their original Baltimore stomping grounds, they’re within the Marbles’ reach at long last. All Connie and Raymond need is to discover exactly where their rivals are hiding out, and then their longed-for war for filth supremacy can begin!

If war is what you want, and strategic intelligence is what you need, then the time-tested approach is to engage a network of spies. After an unsuccessful try or two, Connie hires a she-sleazoid called Cookie (Cookie Mueller) who lives up to her highest hopes. Cookie positions herself as Crackers’s latest supposed conquest, gaining thereby access to the family trailer, and enabling her to eavesdrop on all Divine’s plans. She has to endure a threesome with Crackers and one of his chickens to do it, but Cookie gets all the goods for the Marbles: the location of the trailer, Divine’s current alias, the composition of her retinue, and best of all the details of the birthday party that the family means to throw for Divine in about a week’s time. Knowing the latter gives Connie and Raymond a chance to issue the perfect declaration of hostilities. As soon as they hear from Cookie, they rush straight to the post office to mail her an anonymous present in the form of a gift-wrapped human turd. The Marbles list their return address only as “The Filthiest People Alive.”

Waters originally wrote and filmed several rounds of coup and counter-coup for the Feud of Filth, but most of them were cut when the initial edit of Pink Flamingos clocked in at a preposterous two and a half hours. The released print includes just four such incidents, two of which occur more or less simultaneously. First Connie and Raymond sic the police on Divine’s birthday party. Although that certainly disrupts the festivities, Divine comes out on top when she and her guests kill and eat the arresting officers. Next, the two sides mount concurrent raids on each others’ homes. (The scene explaining how Divine learned the Marbles’ names and address thanks to her gossipy friend, Patty Hitler [Pat Moran], was one of those that wound up on the cutting room floor.) Connie and Raymond stick with the classics for their attack, and burn their rivals’ trailer to the ground when they find it unoccupied. Divine and Crackers show more imagination. They throw Channing to the breeding slaves (Susan Walsh and Linda Olgeirson) and spiritually contaminate the house by licking everything in it. They’re just completing their curse upon the premises with a mother-son blowjob when they hear the Marbles pulling into the driveway, forcing them to withdraw via the back door. Mind you, Connie and Raymond won’t have long to worry about being “rejected” by all their furniture and housewares. When Divine and Crackers come home to a smoldering pile of rubble, they turn right back around and abduct their enemies. With the villains safely in hand, Divine summons reporters from all the nation’s slimiest news outlets to witness the grand finale— the extrajudicial trial, conviction, and execution of Connie and Raymond Marble for the crime of assholism. And then, as everybody knows, Divine does something to place her status as the Filthiest Person Alive permanently beyond question.

John Waters once said of this movie, “I was high when I wrote Pink Flamingos. I was not high when I shot it.” I think that’s basically the Rosetta Stone for the film, in ways both obvious and not so obvious. To begin with the former, that quote emphasizes how Waters’s early movies both were and were not the larks of a young weirdo putting his upper-middle-class privilege to the most outlandish and outrageous use that he could imagine. That is, they might begin with Waters and his friends spitballing ideas to piss off the squares while roaming the bizarrosphere on pot, pills, and acid, but the men, women, and somewhere-in-betweens of Dreamland Studios were some committed motherfuckers when it came to getting those ideas onto film. Shooting in the rusted-out wreck of a trailer, in an overgrown field behind a commune of crazy people, in the depths of a Baltimore winter, may be a different kind of Hell than what Tobe Hooper famously put his cast and crew through while making The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, but it was by all accounts Hell of a comparable degree. And let’s face it, there’s no gainsaying the valor or loyalty of a man who’ll agree to eat fresh dog shit when he’s eight miles high, and then actually make good on the promise when his synapses are clean of cannabinoids. None of these people may have been able to hold down a job to save their lives, but the work ethic on display here is astounding.

When you prod a bit at that Waters quote, however, it gets at something else about this movie beyond the drive and devotion of the Dreamlanders. Waters, when sober, could stand by what he wrote when he was high because the outrages spat out by his drug-addled imagination were coded proxies for things he genuinely believed in. I’m not talking about just the confrontational trash esthetic of Pink Flamingos, either, although that’s certainly part of it. I’m talking, rather, about what Waters means when he calls these characters “Filthy.” Filth in Pink Flamingos is more than criminality or sexual deviance or a diseased sense of beauty and style. Even cruelty, insanity, excess, and libertinism are only the beginning. As represented here, Filth is a philosophy of total contrarianism against everything that society teaches us to value— but also a philosophy that demands creativity and refinement in doing all the things you’re not supposed to do. For the Marbles to kidnap hitchhikers and make breeding stock of them is evil, but for them to sell the babies exclusively to lesbians (whom pretty much all of American society agreed should not be raising children in 1972), and to force a gay man to do the impregnating? That’s Filthy. Likewise, murdering the Marbles in reprisal for burning down the Divine family trailer is mere revenge; it’s the farce trial and the tabloid press conference beforehand that elevates the crime to the level of Filth. This is not to say that Divine’s remarks to the press (“Kill everyone now! Condone first-degree murder! Advocate cannibalism! Eat shit! Those are my politics— filth is my life!”) should be taken at face value as a statement of Waters’s own beliefs, but by putting such words in his antiheroine’s mouth, he’s in essence proclaiming the virtue of the shockingly unacceptable— and that’s something that Waters believed in most fervently.

Can you believe the B-Masters Cabal turns 20 this year? I sure don't think any of us can! Given the sheer unlikelihood of this event, we've decided to commemorate it with an entire year's worth of review roundtables— four in all. These are going to be a little different from our usual roundtables, however, because the thing we'll be celebrating is us. That is, we'll each be concentrating on the kind of coverage that's kept all of you coming back to our respective sites for all this time— and while we're at it, we'll be making a point of reviewing some films that we each would have thought we'd have gotten to a long time ago, had you asked us when we first started. This review belongs to the second roundtable, in which we each focus on those odd, dusty corners of the cinematic universe that have become our particular fixations. For me, that means the prehistory of the slasher film, 70's fadsploitation, the works of local antihero John Waters, and movies touching on musically-oriented countercultures, punk rock especially. Click the banner below to peruse the Cabal's combined offerings:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact