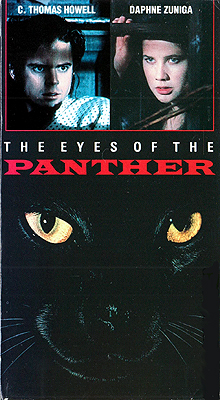

The Eyes of the Panther (1989) *½

The Eyes of the Panther (1989) *½

The Eyes of the Panther is the odd one out among the four mini-movies produced for Showtime under the “Shelley Duval’s Nightmare Classics” banner. Carmilla, The Turn of the Screw, and especially The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were all based on widely-read novellas with reputations that preceded them, each with several (to say the least) previous film adaptations under its belt. By contrast, I had never heard of Ambrose Bierce’s short story, “The Eyes of the Panther,” when I saw the movie in its original broadcast, and only quite recently did I have occasion to read the tale for myself. Nor is it among the undeservedly small corpus of Bierce’s fiction that gets frequently anthologized. “The Eyes of the Panther” is not so much a Nightmare Classic, then, as a Nightmare Curiosity. Mind you, I count it a worthy subject for adaptation for that very reason, especially since its author has been all but ignored by commercial filmmakers despite a sizable body of memorable and groundbreaking work. Alas, it must fall to somebody else to do the story cinematic justice, as Showtime’s The Eyes of the Panther is much the weakest item in the “Nightmare Classics” package.

Youthful frontiersman Malcolm Barrington (John Stockwell, from Christine and Turistas) is out hunting one afternoon when he hears a woman’s voice calling for help. When he goes in search of that voice’s owner, however, he finds instead a panther, which chases him all the way to the front stoop of a ramshackle log cabin. (Incidentally, it’s clear enough from context that when Ambrose Bierce said “panther,” he meant Puma concolor, which used to be common throughout North America before most of them fell victim to Manifest Destiny. Director Noel Black bizarrely gives us instead a melanistic leopard, which has never lived in this hemisphere outside of captivity.) Malcolm’s longrifle misfires, and the cat leaps— but no sooner does Barrington avert his eyes from the seemingly certain death hurtling toward him than it vanishes without a trace. The previously unseen woman (Daphne Zuniga, of The Dorm that Dripped Blood and The Fly II) puts in an appearance at that point, and Malcolm has just enough time to commit her features to memory before he faints dead away from the emotional strain of his narrow, inexplicable escape.

Barrington doesn’t wake up until after sunset, by which time he’s been brought inside the cabin and made something like comfortable by the owner of the place. That would be Jenner Brading, who is played by the 20-something C. Thomas Howell (Camel Spiders, The Hitcher), even though he’s supposed to be pushing 80. The combination of rubbery old-age makeup and Howell’s hapless efforts to portray a man half a century his senior yields arrestingly absurd results. I somehow couldn’t look at him without thinking of Mark McKinney’s Chicken Lady character from “The Kids in the Hall.” Anyway, Brading becomes agitated when Barrington explains how he came to be passed out on the ostensibly older man’s doorstep. It seems Jenner knows Malcolm’s mystery woman— in fact, he has a picture of her that he drew himself— but it’s impossible for Barrington to have seen her, because she’s been dead for decades. Allow Brading to explain…

He begins his tale in an odd place, with a nightmare once had by an Ohio frontierswoman named Sarah Marlowe (Ruth Delosa, from The Killer Within Me) in which she dreamed of her infant son being mauled to death by a panther. Sarah was the wife of a homesteader called Charlie Marlowe (Jeb Brown), but the lady was pitifully unsuited to taming the Wild West— even back when the Wild West just meant Youngstown. Her temperament was nervous, fretful, and fearful at the best of times, and she often dreamed of various disasters befalling herself and her loved ones. On this occasion, Sarah’s nightmare was so vivid that she awoke convinced that it had really happened, and she wouldn’t be placated until Charlie had shown her both her perfectly intact son and the complete absence of DIY graves from the front yard. For his part, Marlowe was never very sympathetic to his wife’s phantasmal fears— not with so much work to be done wresting a living from the uncooperative hills, and a second baby on the way in just a few months. He paid scant attention to Sarah’s maundering about panthers before tromping off to hunt up some meat, leaving her to fend for herself.

That night, however, with Charlie still miles from home, the baby-eating cat of Sarah’s nightmare did indeed stop by for a visit. Even so, it wasn’t the interloping predator that did the damage. So intent was Sarah upon keeping her son away from the panther that she herself killed the boy, smothering him in the folds of her dress as she bunched the two of them up in a far corner of the cabin. She was never the same after that, and not even the healthy birth of her new baby— a daughter whom Charlie dubbed Irene— was enough to restore her to even a semblance of sanity. It was therefore something of a mercy when Sarah died a few years later, leaving Charlie and Irene to abandon their sorrow-haunted homestead for other territories deeper in the West.

For thirteen years, the pair wandered from one frontier town to the next, rarely settling in any of them for any length of time. I think we’re supposed to take that as foreshadowing, but Brading narrates it so matter-of-factly that it doesn’t seem obviously significant in the moment. Anyway, the point is, Brading had an onion tied to his… no, wait… The point is that Marlowe eventually wound up in Ellswood, which was where Brading was living in those days. Which means that despite all evidence to the contrary, his story is going somewhere after all. And sure enough, little Irene was big enough by then to be played by Daphne Zuniga for the remainder of the flashbacks, while Brading was young enough for C. Thomas Howell to use his real face— so there’s a point to casting him as a man three times his age, too! As the keeper of Ellswood’s general store, Jenner was obviously well placed to meet the Marlowes soon after their arrival in town, and he quickly fell in love with Irene. His feelings were plainly returned, too, but for some reason the girl invariably changed the subject whenever Jenner began talking about the two of them getting hitched someday. Eventually, tired of the constant evasions, he asked her straight out to become his wife; he was not at all prepared for her answer. Irene professed her love for him as always, but said that it was impossible for her to marry him— or anyone else, either— on the grounds that she was insane. She wouldn’t say how she arrived at that conclusion, nor would she describe the symptoms of her supposed madness. Furthermore, Jenner got very little closer to an answer when he went to plead his case to her father later on. Charles, for his part, was happy to learn that Irene had a suitor, and deflected the question of her sanity by calling her “imaginative.” Something was clearly fishy, though, because Marlowe was in a big hurry to get Brading out of the house before he got too curious about the groaning, growling noises coming from behind the locked door to one of the bedrooms in his cabin.

I think you have some idea where this is all going, right? The real reason for Irene’s reluctance to marry is because something of that panther’s spirit entered hers when her pregnant mother had the fright that claimed her first child’s life all those years ago. Most of the time, that just made Irene a little eccentric— like when she’d hiss at people she didn’t like, or rhythmically scratch her fingernails against anything rough and grippy. But sometimes in the night, a powerful urge to hunt would come over her, and it would suck to be the local livestock. Worse yet, just once in a while, Irene’s nighttime hunting excursions would cause her to transform physically into a panther. Now we already know from the framing story that Irene never lived to be much older than she is in the flashbacks, but this Eyes of the Panther arrives there by a more convoluted process than you’d ever guess based on Ambrose Bierce’s version. His climax (in which Brading shoots a panther trying to sneak into his house, but finds Irene at the end of the trail of blood when he ventures into the woods to finish off the wounded animal) is in here, but we’ve still got a whole ’nother act to go once we reach it. The “Nightmare Classics” Jenner turns out to be an open-minded sort, for whom even lycanthropy isn’t a deal-breaker in and of itself. His and the Marlowes’ neighbors, though? They’re a bit less understanding…

I was being a trifle disingenuous before, when I said that it would have to fall to others to give “The Eyes of the Panther” the cinematic treatment it deserves. That’s because the best imaginable film version already exists; it’s called Cat People. You see, the original tale is a ruthlessly efficient little narrative, consisting of just three scenes: a successful frontier lawyer’s rejected marriage proposal, his girlfriend’s seemingly irrelevant story about a long-ago tragedy involving her mother and a cougar, and the aforementioned late-night clash between the lawyer and a big cat that turns out to be his lover in animal form. Everything else that you see here— every point on which The Eyes of the Panther differs from Cat People outside of the Wild West setting— was added by screenwriter Art Wallace in a desperate scramble to fill even a one-hour “Nightmare Classics” running time. To the best of my knowledge, neither Val Lewton, nor Jacques Tourneur, nor anyone else associated with Cat People has ever acknowledged any debt to Ambrose Bierce, but the similarities are too pronounced not to raise suspicion. The female were-cat even has the same name! But regardless of whether it got that way by borrowing on the down-low or by convergent evolution, Cat People shows clearly what could have been done with Bierce’s original story. Given the core commonalities between that film and this one, it’s worth bearing Cat People in mind as a counterexample while we consider what went wrong with The Eyes of the Panther.

More than anything, what went wrong was the decision to entomb the entire plot within a succession of decades-old flashbacks. One could argue that doing so is tonally true to Bierce’s tendencies as a writer, since quite a few of his spook stories are put together that way, but I would counter that the tales in question include much of his weakest material. Those stories lose the urgency necessary to effective horror amid the extra layers of distancing which flashbacks create, and the same holds for The Eyes of the Panther. Beyond that, although a flashback of sorts is central to the source material, this Eyes of the Panther not only reassigns the tale within the tale to a different narrator, but reassigns it to one with no direct connection to the person whose history he recounts. Although the question will be more or less answered later, the natural response when Jenner Brading starts talking about Sarah Marlowe’s panther trouble is to ask how the fuck he knows what happened to some other guy’s wife, whom he never even met, on a night when nobody but her was around to see it anyway. Finally, The Eyes of the Panther achieves exactly the wrong kind of verisimilitude by having a doddering old man ramble for approximately half the running time before the object of his narrative so much as appears on the horizon. If I may be permitted two “Kids in the Hall” references in a single review, I kept expecting Brading to break off and say, “Then, in the summer of ’69, I grew a tail.”

A second set of difficulties arises not from the flashbacks per se, but from the order in which they and the framing segments are arranged. That is, it’s never entirely clear who the protagonist of this story is supposed to be. Malcolm Barrington is the first character we meet, and the last one on the scene after the framing story finally ties itself into the main action at the end, but he never actually does anything. Jenner Brading, meanwhile, is completely absent from one half of the flashback story, and Irene’s parents are largely absent from the other. Irene herself is either unborn or dead for much of the film, and is never treated as a viewpoint character in any event. Taken together, the major figures’ wanderings onto and off of the stage deprive The Eyes of the Panther of any single, continuous through-line. Some movies are able to make a virtue of keeping the audience in the dark as to whom and what they’re really about until the very end, but this is not one of them.

Can you believe the B-Masters Cabal turns 20 this year? I sure don't think any of us can! Given the sheer unlikelihood of this event, we've decided to commemorate it with an entire year's worth of review roundtables— four in all. These are going to be a little different from our usual roundtables, however, because the thing we'll be celebrating is us. That is, we'll each be concentrating on the kind of coverage that's kept all of you coming back to our respective sites for all this time. For our final 20th-anniversary roundtable, to which this review belongs, we're looking forward instead of back, to write up some movies of types that we intend to cover more frequently in the years to come. Click the banner below to peruse the Cabal's combined offerings:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact