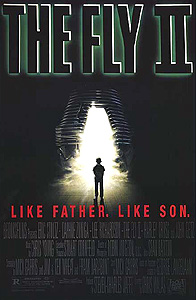

The Fly II (1989)**

The Fly II (1989)**

I suppose it’s only fitting that a sequel to David Cronenberg’s loose remake of The Fly should take the form of an extremely loose remake of Return of the Fly. And if Cronenberg had had anything at all to do with the creation of The Fly II, the result might easily have turned out just as well as Return of the Fly had. Unfortunately, Cronenberg’s sole involvement in this sequel takes the form of a few film clips from the preceding movie, and The Fly II might justly have been advertised with the tag line, “a film that pushes the outer limits of mediocrity.”

I’ll say this for The Fly II’s creators, however: at least they got an actress who dimly resembled Geena Davis to stand in for her in the one scene that Veronica Quaife figures in. Veronica, as you may recall, was pregnant with the offspring of human fly Seth Brundle when last we saw her, and there was every indication that her pregnancy post-dated Brundle’s disastrous chromosomal merger with a housefly in an accident with his homemade teleportation machine. Evidently Bartok Industries, the company that was funding Brundle’s research, had a hand in cleaning up the mess after Brundle’s death, because Veronica, rather than getting that abortion she wanted, has carried Brundle’s child to term and is now giving birth to it in a laboratory at Bartok headquarters. Veronica dies with her feet in the stirrups, but the baby, which somebody names Martin, is alive and apparently almost normal. Or so it seems at first, anyway. As time goes on, Doctors Jainway (Ann Marie Lee) and Shepard (Frank C. Turner, from Watchers and It), under whose supervision the child was placed after being born, discover that little Martin is growing at a vastly accelerated rate. At the age of eleven months, he already has the body of a four-year-old. Not only that, chromosomal analysis determines that there are some extremely odd codons in Martin’s DNA. The strange genes are apparently dormant, but who knows how much longer that condition will last? Through no means that could possibly be explained in real-world terms, the eponymous head of Bartok Industries (The Exorcist III’s Lee Richardson) manages to keep Martin under observation and quarantine in the basement of his laboratory complex for the next five years, over the course of which he grows first into Harley Cross (of The Believers), and then into Eric Stoltz (from The Prophecy and Anaconda).

Meanwhile, Bartok has claimed possession of Seth Brundle’s two surviving Telepod units. The computer controlling them seems to have been destroyed at some point during the climactic chaos of the last movie, because the machines no longer work worth a damn. Not only have they reverted to their old trick of fucking up any living thing that is sent through them, they don’t even seem to be able to handle the much lesser challenge of transporting complex inanimate objects like telephones or computer components. It doesn’t take a terribly clever person to figure out that this is the real reason why Bartok has been so zealous about keeping his hands on Martin. The boy is at least as brilliant as his old man, and Bartok reasons that once he grows up, he might be able to determine what the Bartok Industries scientists have been doing wrong. Martin’s ultra-rapid growth means that Bartok doesn’t have to wait very long; Brundle the Younger is physically mature by his fifth birthday, and in celebration, Bartok moves him out of the lab where he has thus far spent his life and into a swank apartment just beyond the compound grounds. He also offers Martin a job, which the boy eagerly accepts.

The next hour and change is little more than one continuous illustration of the old adage, “like father, like son.” Martin does indeed puzzle out the mysteries of his father’s device, and along the way, he falls in love with a coworker, a night-shift file clerk named Beth Logan (Daphne Zuniga, of The Dorm that Dripped Blood and The Initiation). Like his father before him, Martin takes on his new girlfriend as an assistant of sorts on the Telepod project. And again like Seth Brundle, Martin has a falling out with his new love over a stupid but ominous misunderstanding. Beth works in the genetics department of the Bartok complex, and when she invites Martin to join her at a company party, he overhears some of her coworkers talking about an experimental subject they call Timex— because it takes a lickin’ and keeps on tickin’. Martin sneaks out of the party, and tracks down the part of the lab where Timex is kept. To his horror, the fabled creature turns out to be a dog that was rendered monstrous by a trip through the Telepods two years before. Brundle had befriended this animal as a child, and Bartok had assured him that it was euthanized immediately upon the unsuccessful conclusion of the experiment in which it participated. On the assumption that Beth, as an employee of the genetics department, was aware of Timex's existence, and holding her thus at least partly accountable for the animal’s suffering over the previous two years, Martin stops talking to her after chloroforming the unfortunate beast to death himself. It isn’t long, though, before calmer reflection convinces Martin that Beth’s culpability for Timex’s woes had been minimal at worst, and he makes up with her (complete with make-up sex) after what seems to be about a week of sulking.

Now let’s talk about those dormant genes of Martin’s for a moment. Those of us who have seen The Fly already realize that they came from the housefly that merged with Brundle’s father way back when. And knowing what we know about monster movies, we also understand that it’s just a matter of time before those genes switch on and start turning Martin into a monster very much like the one his father had become. The trigger in this case proves to be Martin’s growth to maturity. Now that he’s an adult, those fly genes kick in and start having their way with him. At first, Martin believes the changes he’s undergoing are the beginning of the terminal phase of the metabolic disorder he’s lived with all his life. The Bartok scientists know better, though, and they go straight to the boss the moment the boy’s periodic blood tests turn up signs that the dormant DNA has woken up. This is actually what Bartok has been waiting for all along. With a unique organism like Martin at his disposal, along with the means to create more like it using the Telepods, Bartok envisions his company cornering the biotechnology market which Brundle’s invention will do so much to create. Transferring Beth to another wing of the company so as to get her out of the way, Bartok sets about putting the lockdown on Martin, but he has miscalculated seriously. Unbeknownst to Martin, Bartok had rigged his apartment with surveillance cameras just like the ones under which he was forced to live at the lab, and those cameras captured every second of the action on the night when Martin took Beth back to his place. Security chief Scorby (Gary Chalk, the voice of Optimus Primal on “Transformers: Beast Wars”) just can’t resist giving Beth a copy of the tape of her and Martin in bed along with her transfer papers, and Martin is apprised of Bartok’s duplicity within hours. Martin’s newly developed fly-strength and fly-agility give him the edge he needs to escape from the lab complex with Beth, and though Bartok’s men do eventually catch up to the fugitives, they’d really have been better off letting them go. That cocoon Martin spins himself is going to hatch sooner or later, and I’m betting it’s going to take a hell of a lot more than Scorby and his rent-a-cops to deal with whatever crawls out of it.

Though I admit to doing this myself, the term “unnecessary” gets thrown around way too often in disparagement of sequels. After all, up until recently only a tiny handful of movies were conceived from the beginning as the first entry in a series, and it would be a foolhardy filmmaker indeed who put together a movie in such a way that a sequel was needed in order to make sense of it (although I can think of a few examples of precisely that mistake). In the vast majority of cases, it’s money and money alone that determines whether or not a sequel to a given film will be made. That said, I can think of very few instances in which that fact was more blatantly evident, or in which the financial calculus of sequel production did the original work a greater disservice, than that of The Fly and The Fly II. 20th Century Fox should be ashamed of themselves for turning director Chris Walas and Mick Garris’s battalion of screenwriters loose to follow up one of the smartest, most complex, most poignant horror movies of the 1980’s by making yet another goddamned Alien rip-off. All the usual stereotypes are here. Doctors Jainway and Shepard could be interchanged with any pair of conscienceless private-sector movie scientists, and nobody would ever notice the difference. The only thing that would bring Bartok closer to the standard-issue Evil Capitalist would be if Bartok Industries had an explicitly named bio-weapons division organized to exploit Martin and the Telepods. And all that differentiates the movie’s climactic showdown from the similar scenes in half a hundred contemporary sci-fi monster flicks is the fact that we’re supposed to be rooting for the monster. The Fly II is well enough made, from a technical standpoint— the acting is passable, the sets are convincingly constructed if not imaginatively designed, and the gore and monster effects are arguably a step up from those in its predecessor— but the film has no good answer to offer to the question, “Yeah, but what's the point?”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact