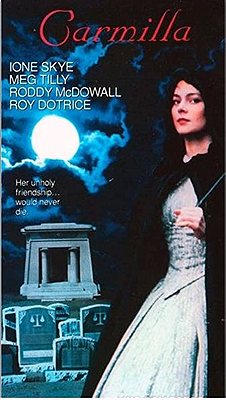

Carmilla (1989) **˝

Carmilla (1989) **˝

I feel like I talk about this a lot, but that’s only because it’s still novel and in some ways faintly marvelous to me: nowadays, you can just get shit. It might cost more than you consider reasonable, and you probably can’t find it in a store unless it’s something brand new that everyone else wants, too, but if you’ve got the money, and don’t require instant gratification, then practically anything that was ever a product of Western mass manufacturing is obtainable without much effort at all. It didn’t use to be that way, and I think it’s mentally and emotionally healthy for those of us old enough to remember the change to contemplate it occasionally. An example from my own experience: in the late 1980’s, during my Lost Boys- and Near Dark-induced vampire phase, I learned about J. Sherridan Le Fanu’s “Carmilla,” and conceived at once a burning desire to read it. Unfortunately, pretty much everything of Le Fanu’s was out of print at the time, so I was out of luck unless and until I could be in exactly the right place at exactly the right time to snag a used copy of one of the various books in which the tale was collected. It took most of a decade for that to happen. I relate that anecdote to explain why I spent so many years treasuring the lumpy and somewhat disappointing version of Carmilla that aired on Showtime in 1989 as part of Shelley Duval’s “Nightmare Classics” package. It has faults galore, no getting around that, but until that beat-up paperback copy of Seven Masterpieces of Gothic Horror turned up at Barbarian Books, it was the only version of the story I could find.

A “Nightmare Classics” budget was never going to stretch far enough to simulate 19th-century Styria, so this version of Carmilla relocates the story to the next best place within its price range— northern Louisiana or Mississippi, circa 1870. Plenty of nominal aristocrats who’ve fallen on hard times there, together with plenty of rambling, shabby estates cut off from one another by miles and miles of nothing. Ex-planter Leo (Roy Dotrice, of Tales from the Crypt and Hellboy II: The Golden Army) has seen his fortunes decline so far that his present household seems to consist solely of himself, his teenaged daughter, Marie (Haunt’s Ione Skye), and a pair of black servants whom Leo apparently managed somehow to retain even after they had a choice in the matter. In the case of Miss Hodgett (Armelia McQueen), I suspect that affection for Marie was the decisive factor, for Hodgett is plainly very fond of the girl. Leo’s wife disappeared mysteriously right after the war. He figures she must have run off with a Yankee soldier; after all, she always was restless on the plantation, constantly badgering Leo to take her to this place or that. Anyway, Leo enjoys his solitude, so the current state of affairs doesn’t bother him much. Marie, however, is bothered a great deal. She never sees anyone whom she could plausibly consider a peer, and with the plantation no longer a going concern, she rarely has contact even with her father’s business partners. Miss Hodgett is the closest thing to a friend the poor girl has! Leo is not totally insensitive to Marie’s loneliness, though, his own solitary constitution notwithstanding. He recently made arrangements to host the daughter of an acquaintance of his— an old military man, retired now like himself— for some weeks. But when the carriage that was supposed to deliver the other girl arrives, the driver is carrying a letter of regret instead. Evidently there’s a bad illness going around down south, and the general’s daughter has caught it. She’s much too sick to travel right now. The general’s letter says nothing about symptoms, but from the eagerness with which the carriage driver buys a voodoo charm from Miss Hodgett before getting on his way, I’m guessing the disease is something out of the ordinary.

A strange and in some ways fortuitous thing happens that night. While Leo and Marie are out for a moonlit walk together, they witness a carriage wreck on the road leading past their property. The driver and two of the passengers are crushed to death in, under, and around the mangled vehicle, but one other— a girl about Marie’s age (Meg Tilly, from Psycho II and The Girl in a Swing)— is thrown clear and survives. Leo brings the girl to the house, and summons the neighborhood doctor (John Doolittle, of RoboCop 2 and The Clan of the Cave Bear) to examine her. The doctor finds nothing seriously amiss, and sees no reason why she shouldn’t make a full recovery given sufficient rest. As for the dead folks from the carriage, Leo orders them interred in the family crypt. Bodies rot fast in the nigh-tropical Southern summer, so there’s no time to waste figuring out who they were or where their remains rightly belong.

Upon regaining consciousness, the injured girl identifies herself as Carmilla. The older women who didn’t survive the crash were her mother and a lady in waiting. What remains of her family is quite far-flung, so there’s really nothing else for it but to take Carmilla on as a long-term guest until some living relative of hers can be reached. Marie is thrilled with the prospect, of course. However, the adults in her life are somewhat nonplussed with her new friend. Some of Carmilla’s peculiarities can be written off as lingering symptoms of the concussion she got when she was thrown from the carriage, or as the natural emotional effect of losing her mother. Others, though, might more properly be termed manifestations of a Romantic temperament. Carmilla’s moods are vast, changeable, and intense. Her habits and attitudes, meanwhile, are distinctly unconventional. She eats almost nothing, stays up all night, and then doesn’t rise from her bed until well into the afternoon. She harbors a horror of death and illness that seems more than rational. And she quickly forms an attachment to Marie with all the fervor of a male suitor. Even Marie is a little spun by that, but she also finds it exciting in a way she doesn’t fully understand— again, rather the way she’d no doubt respond at her age, and with her degree of social inexperience, to being wooed by a male. Most of all, though, Carmilla has some extremely forward-thinking notions about “proper” femininity, and about the sort of men who invest heavily in its upkeep. Although she flirts a bit with Leo at first, she later offers Marie a scathing assessment of his motives for allowing her to remain as a guest in his house, and she stridently disapproves of the seclusion in which Marie has been kept all these years.

There’s a bigger worry taking shape, though, than whether Carmilla is a bad influence on Marie. Very soon after Carmilla gets back on her feet, rumors begin circulating among the local low-caste rabble that “the sickness from the south” has arrived. In fact, it looks like it might even have put in an appearance at the plantation itself. Miss Hodgett has been in the habit lately of allowing a homeless orphan to sleep out on the back porch. She makes sure the kid gets enough to eat, too, and one morning when she brings him his breakfast, she finds the boy inexplicably dead. The doctor can detect no disease symptoms that he recognizes— just a couple of small, unimportant-looking puncture wounds on the throat. We, however, know perfectly well that the orphan didn’t die of any disease. The last we saw of him, he was being awakened and attacked by somebody in a heavy, hooded mantle.

Miss Hodgett thinks she knows what’s what, especially after Marie begins ailing of something else that the useless-ass doctor can’t identify. The housekeeper’s considered opinion is that Carmilla herself is behind Marie’s turn for the worse, and probably all the sickness on the surrounding subsistence farms, besides. Hodgett is at least partially right, for Carmilla is one of a whole nest of vampires, together with those “dead” women whom Leo considerately installed in his own family crypt. Unfortunately, the method whereby Miss Hodgett confirms her suspicions (serving up the garlickiest dish in her repertoire at dinner the following night) has the effect of alerting the vampire that she’s been found out. Before Miss Hodgett has a chance to tell anyone else what she’s learned, or to act on it herself in any way, she gets nibbled to death by a swarm of vampire bats under Carmilla’s control. Of course, mass bat attacks indoors tend to attract their own sort of attention, and Carmilla soon finds herself contending with an eccentric police inspector (Roddy McDowall, from Shakma and Mean Johnny Barrows) who’s as ready to believe in the undead as any old voodoo witch.

From Blood and Roses in 1960 until The Hunger in 1983, “Carmilla” and the lesbian vampire tradition arising from it were consistently exploited to make vampire movies sexier. In 1989, however, pop culture was no longer in the mood, at least in the United States. Edwin Meese, Andrea Dworkin, and AIDS had collectively seen to that. And in any case, it would have been way out of character for producer Shelley Duvall to go courting the infamous Male Gaze in the manner of Lust for a Vampire or Vampyros Lesbos. Instead, writer Jonathan Furst and director Gabrielle Beaumont have taken Carmilla in the opposite direction, attempting to situate it as a parable of female liberation. Forbidden physical intimacy is only a small part of the temptation with which Carmilla plies Marie. Much more important— and much more compelling from Marie’s point of view— is her promise to get Marie out from under her father’s thumb and out into the world. When Carmilla encourages Marie’s resentment of her cloistered lifestyle, or points out the domineering attitudes of Leo, the doctor, and the inspector, she’s speaking nothing but the manifest truth. The trouble is, Furst and Beaumont don’t go far enough for their reinterpretation to stick. Victorian moralism is marrow-deep in this story, and it can’t be extracted without changing the climax beyond recognition. But not only does this Carmilla not do that, it instead actively undermines the new message by allowing Leo to be right about everything in the end— even about stifling and restricting Marie’s mother. Then, an epilogue makes matters worse by attempting to walk that back a bit, before walking back the walking back, and finally walking back the walking back of the walking back! By the time the credits roll, it’s simply impossible to say any longer what this movie’s perspective on Carmilla herself even is.

It’s a damn good thing, then, that Meg Tilly gives such a riveting performance. Don’t ask me how she does it, either, because part of what makes her stand out so from the other actresses who’ve assayed the part over the years is her commitment to Le Fanu’s portrayal of Carmilla as languorous, passive, and lacking in all normal departments of vitality. She’s as far from Ingrid Pitt’s conniving, carnal puppet-mistress (as seen in The Vampire Lovers) as it is possible to be. Yet just lounging around doing nothing, Tilly fascinates and commands, in ways that her remarkable beauty can’t account for on its own. This might honestly be the best screen portrayal the character has enjoyed to date. I just wish I could say Carmilla was fully worthy of it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact