Django Unchained (2012) *****

Django Unchained (2012) *****

If there’s an action movie theme more popular than revenge, I surely don’t know what it might be. It’s no challenge to figure out why, either. The urge to repay wrongdoing in kind is among the most basic bits of human psychology. It underlies the earliest recorded laws; it serves as the organizing principle of honor cultures around the world; it’s been a driver of human history for as long as there’s been such a thing as human history. Revenge is thus one of the most accessible of all fictional tropes, but that very accessibility makes it much easier to use than to use well. Django Unchained got me thinking about what using it well really means, because this is hands-down the best revenge movie I’ve seen in ages. And here’s the main principle I’ve arrived at from all that pondering: the difference between a great revenge story and a less-than-great one is specificity. It’s a question of precisely tailoring the retribution to the nature and scale of the wrong it’s meant to redress, and of managing the implications of on whom and by whom the wrong is avenged. Let me give you an example…

Black Caesar isn’t a revenge movie in the ordinary sense, but its climax hinges upon one of the most adroitly portrayed acts of vengeance I’ve seen in any film. One of the villains in Black Caesar is a crooked, racist cop named McKinney, while the antihero is a black gangster called Tommy Gibbs. The characters meet for the first time when Gibbs is but a boy who shines shoes for pocket money, and McKinney a low-ranking patrolman. The terms of that meeting are such that Gibbs will forever see McKinney as the symbolic face of white bigotry. When a mafioso hires Tommy as a courier for payoff money to McKinney’s precinct, and the bag comes up short, McKinney takes it out on the boy by framing him for some manner of crime, and beating him so severely that he walks with a limp for the rest of his life. When they meet again at the movie’s end, McKinney is New York City’s top policeman (albeit still utterly corrupt), Gibbs is arguably its top criminal, and a years-long truce between them has erupted into mass violence. That final confrontation ends with Gibbs blackening a wounded McKinney’s face with shoe polish, and then forcing him to sing “Mammy” at gunpoint before bashing his head in with a shoeshine box. It’s the attention to detail that makes it work, you see? What McKinney represents, what the method of his demise represents, the length and the intimacy of the two characters’ hatred for each other. As I said, Black Caesar isn’t really a revenge movie, but nowhere else have I seen retribution against racism in particular so perfectly and evocatively portrayed as in its McKinney-in-blackface scene— until now, that is. The emotional impression left by Django Unchained is much like that of watching McKinney get his comeuppance for two hours and 45 minutes.

The opening shot deserves special attention, because it does more than just to get the movie started. This opening shot is a statement of intent. While a jarringly chipper theme song lifted from Sergio Corbucci’s Django (where its chipperness was equally jarring) plays on the soundtrack, the camera pans across a landscape with “Spaghetti Western” written all over it, finally coming to rest on the whip-scarred backs of five black slaves being marched in irons across the gorgeously inhospitable Texas countryside. So right away, we know four things about this movie: (1) Django Unchained will be leaning heavily on the stylistic conventions of European Westerns; (2) writer/director Quentin Tarantino will have no compunctions about flat-out stealing shit when it serves his purposes; (3) the centrality of slavery to the proceedings will make this story not so much a Western as a Southern; and (4) unlike pretty much every other Hollywood movie ever made about the Antebellum South, Django Unchained will not be the slightest bit ashamed to call out the region’s entire culture for being based on exploitation, brutality, and corruption of the worst kind.

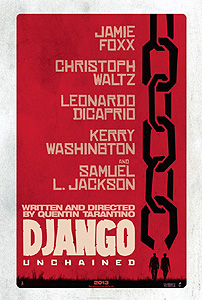

Anyway, among those slaves is Django (Jamie Foxx), formerly of the Carucan plantation. He and his wife, the improbably named Brunhilde von Schaft (her original owners were German), attempted to escape some time ago, but didn’t get very far. Old Man Carucan (Bruce Dern, from The Rebel Rousers and The Haunting) quickly concluded that such resourceful and self-willed slaves were more trouble than they were worth, and after having them whipped and branded as runaways, gave orders for Django and Brunhilde to be taken to auction and sold— separately. Django was bought by the Speck brothers, Ace (James Remar, of The Warriors and Tales from the Darkside: The Movie) and Dicky (James Russo, from A Stranger Is Watching and The Ninth Gate), who are the ones currently trafficking him and his four fellows westward. One night, while the Specks and their captives are nearly 40 miles from the nearest settlement, they are overtaken by Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz, of Pact with the Devil and one of the more recent versions of She). This eccentric gentleman is a German immigrant, a former dentist, and a current bounty hunter, and he wants to buy Django. The Specks find this very suspicious, and refuse the sale— at which point Dr. Schultz shoots both Dicky and Ace’s horse dead, leaving the latter man pinned beneath his fallen mount. His bargaining posture thus strengthened, Schultz draws up a bill of sale, hands Ace $125, and requisitions Dicky’s horse and winter coat for Django. Then he rides off toward the little town of Daughtrey with the bewildered slave in tow, offering as a parting shot to the remaining captives some suggestions as to how they might proceed in the event that they don’t feel like being slaves anymore.

In Daughtrey, Django receives an eye-opening demonstration of Schultz’s bounty-hunting methods. The sheriff of that village (Don Stroud, from Sutures and The Amityville Horror) is a wanted criminal, and Schultz has a warrant for him, dead or alive. Just showing up in Daughtrey with a black man on horseback creates enough hubbub to draw out the sheriff, and shooting the sheriff down in the street before the eyes of half the town similarly suffices to bring the local US marshal (The Hive’s Tom Wopat)— whom Schultz completely flummoxes by presenting his warrant and demanding his $200 bounty. In the quiet moments along the way, the doctor finds time to tell Django that he’s also got a warrant for the Brittle brothers— John (M. C. Gainey, of Unearthed and Club Dread), Ellis (Doc Duhame, from Monster in the Closet and The Open Door), and Roger (Cooper Huckabee, of The Pom Pom Girls and The Funhouse)— who formerly worked as overseers for Old Man Carucan. That’s why King needs Django. He’s never seen any of the men he’s hunting, but Django knows them very well indeed. Schultz therefore offers the slave a bargain: help him find the Brittle brothers, and King will make Django a free man.

Actually, it’s more than just the brothers’ faces that Schultz doesn’t know. The Brittles have been seen recently in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, and it stands to reason that they’d still be working as overseers, but Schultz has no idea who their current employers might be. He and Django will have no alternative but to go from plantation to plantation all around the town until the latter spots their quarry. For that, they’ll need a cover story; the doctor will pretend to be shopping for an experienced, talented, and beautiful house-girl, while Django poses as his freedman valet. After suitably outfitting Django for his role (“You mean you’re going to let me pick out my own clothes?” “Of course.” Cut to Django riding down a country road looking like the Antebellum Disco Godfather.), they start making the rounds— a process which we join as they arrive on the land of a planter known as Big Daddy (Don Johnson, from A Boy and His Dog and Machete). Big Daddy does indeed turn out to be the Brittles’ new boss, and the trio don’t last long after Django catches sight of them. The planter and his associates attempt to avenge the brothers that night, but the undertaking goes… well, let’s call it “explosively awry.”

In the aftermath, Schultz and Django get to talking about the newly freed slave’s plans for the future. Django tells King about Brunhilde (who the accompanying flashbacks reveal to be played by Kerry Washington), which provokes King to tell Django about her legendary namesake, and before you know it, the two men have a new partnership in the works. Schultz and Django will spend the rest of the winter together out West, hunting criminals and splitting the bounties 67-33. Meanwhile, Schultz will teach Django to read and write, and train him in equestrianship and gunfighting. And then, in the spring, they’ll go to Mississippi together to rescue Brunhilde.

That turns out to be a taller order than they realize. The state records office reveals that Brunhilde (entered into the register of sale as “Broomhilda” by the semiliterate clerk) was sold to Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio, of Critters 3 and Inception), whose Candieland plantation is the third-largest in the state, and a byword for suffering among slaves all over the South. Candie made his fortune in cotton, naturally, but his true passion is the bloodsport known as Mandingo fighting— think dogfighting or cockfighting, but with slaves instead of animals. That will be the bounty hunters’ in. King’s character this time will be a man as bored as he is wealthy, who wants to get into the Mandingo fighting racket by purchasing a battle-hardened slave from someone already in the business. Django, meanwhile, will pose as what he calls the lowest form of human life, a black slaver whom Schultz has engaged to help him pick the very best. They’ll engage Candie in a $12,000 deal to buy one of his champion brawlers (a $12,000 deal from which they’ll quietly sneak away under the cover of a supposed trip to the city to summon Schultz’s non-existent attorney), and while that huge sum has Candie distracted, they’ll maneuver him into selling Brunhilde, too, for a few hundred bucks on a cash-and-carry basis. It’s a solid plan, and Brunhilde would be as good as free already if Calvin, his sister (Laura Cayouette, from Pulse 2: Afterlife and Flight of the Living Dead), and his lawyer (Dennis Christopher, of Blood and Lace and It) were all the conspirators had to worry about. Suffice it to say that all the tools in that shed could sorely use a good sharpening. Unfortunately, though, Brunhilde’s would-be rescuers will also be contending with Candie’s slave butler, Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson, from Jurassic Park and Deep Blue Sea). Stephen is the one who really runs Candieland, since Calvin is too lazy to be bothered, and not half smart enough for the job anyway. And as a man who owes all of his power and privilege to a loophole in the South’s racial caste system, there’s nothing he hates more than a free black with ideas above his station as defined by that system.

From the moment I saw the first teaser trailers for Django Unchained, I knew that it was going to be either brilliant or calamitous— no middle route was possible. Quentin Tarantino has been responsible for some of the smartest and most effective genre pastiches of the past twenty years, but he’s also been responsible for some of those years’ most flounderingly self-indulgent messes. On the one hand, he seemed quite earnest about wanting to deal with slavery in a way that American pop culture has always been unable and/or unwilling to do, but on the other, he’s also a twitchy white guy who comes across as way too gleeful about having his characters toss the word “nigger” around. And here Tarantino is, practically remaking Mandingo at a time when privilege-panic is driving America’s still sizable population of racist motherfuckers to become more open and vocal about their bigotry than at any point since probably the 1970’s. Could somebody who so ardently admires and emulates the exploitation movies of ages past really make a film on this subject that would do justice to the gravity of the material?

Actually, watching Django Unchained has convinced me that to ask such a question is to frame the issue exactly backwards. Particularly when compared to “serious” movies about American slavery, Django Unchained demonstrates that there are some things so baroquely horrible that only an exploitation treatment can do them justice. Unless an artist is willing to get their hands dirty; unless they’re prepared to call a monster a monster; unless they feel no qualms about slapping the audience upside the head with atrocities, and rubbing their faces in rank, steaming piles of cruelty— unless, that is, they have the courage not to give a single shit about decency or good taste— then they haven’t a chance of coming to honest grips with something as grotesque as slavery the way it was practiced in the Americas. There is no way to face directly the ingenuity of evil that slavery fostered without being lurid and offensive, because the reality itself was lurid and offensive. To a disgraceful extent, people in this country are still in denial about slavery nearly 150 years after its abolition; we need commercial art about the Antebellum South that is full of rape and flagellation and castration and people being branded in the face. That’s what slavery was, and it’s high time we as a society looked that history in the eye. Amistad, Glory, and “Roots” aren’t going to get us there, whatever their merits otherwise; only something like Django Unchained can do the job.

Of course, there were still a million ways this movie could have gone wrong, which brings me back around to the subjects of revenge and specificity. Glory’s biggest mistake was to act like it was about Matthew Broderick’s character; the worst thing Django Unchained could have done was to act like it was about King Schultz. Fortunately, Tarantino understood that, so although Schultz takes the lead for much of the picture, Django stands alone when it really counts, acting on his own initiative. (And significantly, shit turns ugly for our heroes at precisely the point when Schultz starts giving vent to his own vicarious outrage, rather than facilitating Django’s.) Furthermore, the terms of the endgame make clear that Django’s true enemy is something much bigger than Calvin Candie. To save Brunhilde, Django must fight the whole apparatus of slavery: the plantation owners, the overseers, the slave trackers, the country lawyers, the vigilantes, the genteel enablers who profit from the system at a conscience-salving remove, and even the occasional slave who lucked into a bit of power, and is now willing to become a tyrant in his own right if that’s what it takes to hold onto it.

Yeah, I’m talking about Stephen with that last part. In a film remarkably well laden with unforgettable supporting characters and bravura performances in those parts (even Leonardo DiCaprio is terrific!), Samuel L. Jackson’s Stephen nevertheless stands out. He is simultaneously the vilest, foulest figure in the whole movie and the most compelling. Even more than Calvin Candie, Stephen personifies the corruptive power of the Southern caste system, because Stephen is truly the brains of the Candieland operation. Technically, he is nothing more than a slave and a butler, but he’s the one who manages all of Candie’s accounts while the planter himself devotes his energies to Mandingo fighting. Beyond that, he’s the one who maintains the expected brutal discipline over the other slaves. He’s a master manipulator, who subtly directs the actions of his supposed superiors by tricking them into believing that they thought of his ideas themselves. Most of all, he’s a man who rightly regards himself as the smartest and most talented person he knows, but whose genius has been perverted into evil because the social environment allows him no outlet for it save to be the power behind a corrupt throne. And because his position demands it, Stephen is twice the white supremacist that Candie or his sister or any of their redneck underlings are. Indeed, given both his age (he claims to have been at Candieland for 76 years) and the duties of a house slave, there’s every reason to imagine that Stephen had the leading day-to-day role in raising Calvin— which would mean that Calvin came by his odious attitudes at least partially through Stephen’s own example! So when Django rides in on that horse, flouting every last rule of Southern society, Stephen is absolutely right to regard him as a threat and a natural enemy. And Tarantino is absolutely right to make Stephen Django’s ultimate opponent.

Mind you, Stephen’s position as the baddest of bad guys should not be taken for one second to imply that Tarantino is letting the white characters off. In fact, it’s in the portrayal of whites that we see how uncompromising an indictment of Southern culture Django Unchained really is. On top of all his other disgusting qualities, Calvin is a Francophile who affects to call himself “Monsieur CawnDEE,” yet speaks not a single word of French; he doesn’t even know what “panache” means. He names one of his fighting slaves D’Artagnan, after the hero of The Three Musketeers and its sequels, completely unaware that Alexandre Dumas was the son of a mixed-race freeman and an Afro-Caribbean slave (making him plenty black enough to qualify under the South’s “one drop of blood” rule). He makes a hobby of phrenology (enabling him to bloviate at the slightest cue upon the biological appropriateness of black slavery), and keeps the skull of Stephen’s predecessor, Old Ben, as a ghoulish memento of Candieland’s storied past. His sister seems not so loathsome at first glance, but when Calvin attempts to entertain King and Django by making Brunhilde show off the scars on her back, she objects not on the grounds that it’s cruel, dehumanizing, and nine different kinds of creepy, but rather because the dinner table isn’t the proper place for such displays. Big Daddy and his night riders get what might be the most excoriating takedown of all, when their mounted charge into what they think is Schultz and Django’s campsite gets interrupted by a blackly funny flashback to the mob nearly disintegrating in a petty and petulant squabble over the ineptly cut eyeholes of their proto-Klansman hoods. In short, there’s no “good Southerner” for the white viewer to project himself onto, no contortions of character (such as we saw recently in Jonah Hex and John Carter) meant to establish this or that figure as not that kind of Confederate. Tellingly, the one genuinely sympathetic white character in the whole film isn’t even American! That’s as it must be if the aim is to keep Django’s white ally untainted by slavery, because even the most intensely abolitionist regions of the Antebellum North were compromised not only by history, but by present-day economics. Any Northerner who wore cotton, drank coffee, smoked tobacco, or consumed any of the cornucopia of agricultural products that coped poorly with the harsh winters and short growing seasons above the Mason-Dixon Line was implicated in the slave system, just as surely as the overseer wielding the whip. So again we see Tarantino’s admirable attention to detail, and his careful consideration of what the elements of this movie mean. And just as admirably, we see that Django Unchained aims to be as uncomfortable on the intellectual level as it is on the visceral.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact