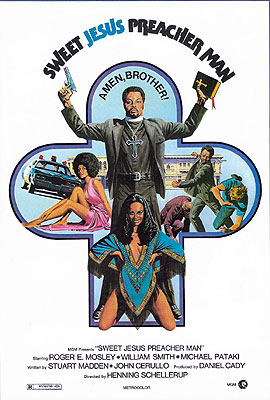

Sweet Jesus, Preacherman (1973) *½

Sweet Jesus, Preacherman (1973) *½

I can’t explain Sweet Jesus, Preacherman. I can describe it; I can synopsize it; I can analyze and critique it. But explain? Account for how or why so thoroughly unprofessional a movie could be made on MGM’s, of all companies, dime? No. That I cannot do. Had Sweet Jesus, Preacherman been produced under the aegis of some outfit like Crown International or Independent International, it would be just an unexceptional half-assed blaxploitation flick, but coming from the majorest of all major studios, this film is weird.

Los Angeles mobster Frank Martelli (William Smith, from Black Samson and Scorchy) has some people he needs killed, and since anybody worth killing is worth killing right, he contracts the job out to Cyrus Holmes (Roger E. Mosley, of Terminal Island and Cruise Into Terror). Some of the other guidos on Martelli’s staff, most notably his right-hand man, Joey (Joe Tornatore, from Cleopatra Jones and Grotesque), don’t approve of the boss hiring a black guy for gigs like that, but fuck them. Holmes is the best in the business (or at least the best in Martelli’s price range), and he’s performed $100,000 worth of hits for Martelli’s gang over the years.

However, when Cyrus comes to collect his fee for the triple killing, he learns that Martelli’s faith in him goes further yet— further, in fact, than Holmes is entirely comfortable with. One of the men Cyrus just whacked was the Reverend Jason V. Lee, newly hired pastor of a church in Watts which has recently attracted Frank’s interest. You see, Martelli is the power behind most of the organized crime in that district. Dope, prostitution, the numbers racket, money laundering— he’s got his fingers in everything. Lately, though, it seems somebody else is trying to muscle in; at the very least, somebody’s been sending Martelli’s men to the hospital and the morgue, and he wants to know who it is. Now Martelli may be a wop, but he knows black neighborhoods well enough to recognize that if you really want to understand what’s going on in one, you talk to the preacher. That’s why he wanted Lee dead. With him out of the way, the mob boss could install an agent of his own in Lee’s church, and use the pastor’s privileged position to spy out the mysterious new player in Watts. The agent Frank has in mind, naturally, is Cyrus, and not just because of his race. Holmes was the son of a crooked preacher, so he’s already been schooled on all the finer points of the salvation racket. There’s 50 grand in it for him if he takes on the assignment, plus maybe a negotiable percentage of all the mob’s earnings from Watts if he succeeds.

Exit Cyrus Holmes, and enter the new and improved Jason V. Lee. None of the parishioners— not even Deacon Elmore Green (Sam Laws, from The Reincarnation of Peter Proud and The Fury) and his wife (Coma’s Amentha Dymally)— had ever seen their new minister, so nobody will ever know the difference. Well, nobody except maybe Detroit Charlie Paff (Chuck Lyles, of The Zebra Force), an old high school classmate of Cyrus’s, who just happens to live in Watts now, and who is sure he recognizes “Reverend Lee” from back home, no matter how much Holmes protests to the contrary. Charlie works as a campaign organizer for Sam Sills (Michael Pataki, from Dracula’s Dog and Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers), the man who represents Watts in the California State Senate. Despite his not very successful efforts to ingratiate himself to the black community, Sills is an old-fashioned machine politician, which means he bears watching closely. If he’s already mobbed up, then he might know something about Martelli’s unseen enemies, and if he isn’t, then the reelection fight he’s facing in November represents an opportunity for Frank to buy himself a Senator. Also on the Sills campaign staff is Beverly Solomon (Marla Gibbs, of Black Belt Jones and The Missing Are Deadly), perhaps the most active member of Holmes’s congregation. She’s visibly attracted to the macho new minister, and her teenaged son, Lenny (Chuck Douglas Jr.), could be a useful source of intelligence on the subject of neighborhood street crime.

In fact, however, the whole theory behind Holmes’s undercover mission in Watts is in error. Martelli isn’t facing competition from another gangster, except insofar as Joey keeps letting his bigotry get the better of him, and interfering with Cyrus’s investigation. His real problem is black nationalist Eddie Stoner (Tom Johnigarn, from The Bad Bunch and Sasqua) and his vigilante squad. They’re the ones who’ve been roughing up pimps and pushers, and they’re also the ones who’ve been stirring up discontent with the ineffectual status-quo liberalism of Sam Sills. Still, Cyrus doesn’t realize what he’s dealing with until Stoner and his crew kill Sweetstick (Damu King, of The Black Godfather and Shaft), a coke dealer working for Martelli, and even then he decides to bide his time until he has a better idea of who and how many Stoner has on his side. Of course, Joey fucks that up, too, by trying to whack Eddie on his own initiative, but getting his older brother, Eli (Chuck Wells, from Trader Hornee and Chain Gang Women), instead. Far from supporting Eddie’s cause, Eli was a freelance numbers runner whose payoffs to the local gangsters had been trickling up to Martelli all along. [Insert “The Price Is Right” loser horn here.]

Meanwhile, there are several factors working against the indefinite continuation of Holmes’s cozy relationship with his employer. Joey, obviously, is starting to piss him off, and some of that irritation is inevitably going to slop over onto Martelli. Then there’s the confession Cyrus hears from Deacon Green, whose nice house and fancy car turn out to have been paid for out of an advance against the five-million-dollar grant that “Lee’s” predecessor, Reverend Foster, lined up for community development shortly before his death. That’s a lot more money to play around with than Martelli’s 50 grand, and it comes with its own built-in laundering mechanism! Cyrus has non-mercenary reasons to turn on the mafia, too. For one thing, his relationship with Beverly Solomon is starting to heat up, and he’s beginning to see her as more than just another angle to play. But more importantly, the longer Cyrus fakes being the semi-official leader of Beverly’s community, the less he seems to be faking. Sure, all his God talk remains so much rote bullshit, reconstructed from memories of his dad’s equally phony preaching. But having so many people trust in him to improve their lives makes Holmes increasingly interested in actually doing it.

The tipping point comes when Lenny Solomon is wounded and a friend of his killed by trigger-happy cops who then attempt to cover their own asses by framing the kids for attacking them with a knife. Pushed by Beverly, Deacon Green, and the congregation in general— and even, in a weird way, by Eddie Stoner and his militants— Holmes does what he imagines the real Reverend Jason Lee would do, and steps up as the spokesman for his people to put pressure not merely on the precinct captain (Norman Fields, of Gas Pump Girls and Octaman), but on Senator Sills as well. There’ll be no cover-up of racist police malfeasance this time. Then Cyrus saves the senator’s electoral bacon by making sure everyone in Watts understands Sills’s role in securing justice for Lenny, his dead friend, and their families, at which point he presents Sills with a revised and even more lucrative version of Foster’s old community development plan. Finally, Cyrus starts leaning on all the criminals in the neighborhood that Stoner’s wannabe Panthers haven’t killed yet, putting them on notice that he’ll be the boss around here from now on. They can think of it as supporting the church if it makes them feel better. Martelli’s not going to like that, of course. But oddly enough, Stoner just might. After all, didn’t Cyrus just rig it so that money generated by black enterprise remains in black hands, even if the enterprise in question happens to be criminal?

It’s a great premise— I’ll give Sweet Jesus, Preacherman that much, anyway. What sends this movie off the rails is first and foremost that its incredibly busy plot (some aspects of which I barely touched on or ignored altogether for clarity’s sake) never arrives at any real conclusion. Open-endedness can be a good thing, certainly. Willie Dynamite, the other film I’m reviewing for the B-Masters’ blaxploitation roundtable, is a sturdy and directly relevant example. But Sweet Jesus, Preacherman comes across more like Tobe Hooper’s Toolbox Murders, in which the money ran out before the ending was shot, leaving Hooper and company to cobble together a new one out of whatever odds and ends of footage they had at hand. Take Detroit Charlie. I left this out of the above synopsis, but he spends the first two thirds of the movie following Cyrus around Watts surreptitiously, hunting for clues to his real identity. In fact, he’s doing that very thing the last time we ever see him. Yet he never witnesses Holmes engaged in any illegalities; never extracts any incriminating information from Foxey (Della Thomas, of Darktown Strutters and Dr. Black, Mr. Hyde), the chatty cocktail waitress at Cyrus’s favorite local bar; never contributes anything to Martelli’s climactic attack on the church; never provides Sills with anything he might use to shift the balance of power between him and the preacher in the senator’s direction. Indeed, for all the scenes he walks though, Detroit Charlie never serves any function in the story at all.

More damaging than any abandoned subplot, however, is the way the main plot just sort of peters out, leaving everything unresolved. The final shootout at the church between Cyrus and a pack of mafia goons led by Joey ends in something like stalemate, with Holmes badly wounded and his attackers exterminated, but Martelli still in power to continue the fight another day. For that matter, it’s not even clear who the gunman in the limo (who fires the shot that really ought to kill Holmes by any sensible reckoning) is supposed to be. The limo itself suggests Martelli, but he never comes across as a do-it-yourself kind of gangster. Or maybe we’re meant to conclude that there really was a rival mob at work in Watts all along, and that Stoner was a red herring so far as Cyrus’s original mission was concerned. However we interpret it, Sweet Jesus, Preacherman ends more like a TV pilot than a feature film, leaving virtually all avenues open for future development. It’s most unsatisfying.

And to get back to what I was saying at the beginning of this review, it also doesn’t make any sense from a production standpoint. I could believe that funding shortfalls left Sweet Jesus, Preacherman without an ending if this had been an independent undertaking, but surely MGM would insist on budgeting enough to get the damned movie finished at least? And surely the studio would similarly insist that any more bearing their logo meet certain minimum standards of technical quality, however big a mess it might be from an artistic standpoint? Then again, this is a conspicuously cheap picture in every other respect, too, with only the assassination by exploding Cadillac that begins the film indicating any willingness to spend money for the sake of production value. Lighting is flat and amateurish, the sets are cramped and junky (although that much at least can be chalked up to realism), and the music is both sparsely employed and thoroughly undistinguished, except insofar as it’s unusual to hear a tuba providing the bassline in 70’s funk. A final, truly bizarre symptom of this movie’s cheapness and/or unprofessionalism can be seen in Roger E. Mosley’s generally adequate performance. On at least two occasions, he seriously flubs his lines, and the verbal stumble is allowed to stand. I suppose it’s possible that the latter is not a mistake, but a deliberate indication of Holmes’s discomfort playing the part of Reverend Lee, since they all occur when the imposter preacher is giving an oration of some kind. However, Sweet Jesus, Preacherman does very little to earn the benefit of any such doubts, and I’m disinclined to extend it in this case. As I said, it’s all very mysterious, especially coming from a big studio like MGM. Perhaps we should take it as a sign of how little regard the company leadership had for their black audiences: “Standards, shmandards— who cares? Ain’t nobody gonna go see it but a bunch of Negroes, anyway…”

As long as we’ve been doing this, it continues to surprise me how much cult-cinema territory remains where the B-Masters have yet to venture as a group. This month, we address one of the really glaring omissions with a roundtable devoted to blaxploitation movies.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact