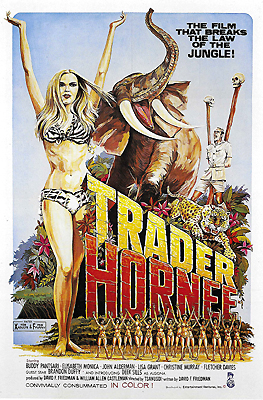

Trader Hornee (1970) -*½

Trader Hornee (1970) -*½

Those of you who were reading 1000 Misspent Hours and Counting back then might have scoffed when I said that was watching and reviewing the 1931 jungle adventure movie Trader Horn primarily so that I would someday be able to cover David Friedman’s soft-porn send-up of the genre, Trader Hornee, on an informed basis. To be honest, even I thought that might have been taking my dedication to doing things in order just a little too far. However, now that I’ve caught up with Trader Hornee at last, I really am glad I made the effort to see the source material first. Believe it or not, this movie is a parody the way Airplane! is a parody, not just poking fun at widely employed genre tropes, but following the plotline of a specific antecedent in fairly close detail. Unfortunately, it is not also Airplane!-like in the sense of being actually funny. As those who know Friedman well will anticipate, Trader Hornee’s comic sensibility is creakily Vaudevillian, like an episode of “The Carol Burnett Show” from a parallel universe where it was permissible to work blue in prime time.

One odd way in which this movie doesn’t line up with its inspiration: Hamilton Hornee (Buddy Pantsari)— he says the Es are silent, but nobody ever listens— is not in any sense a trader. Rather, he’s a private detective, head of the Indianapolis-based Hoosier Secret Service agency. That’s pretty much a very grandiose way of saying that he works alone apart from one secretary, Jane Sommers, who is also his girlfriend. (All the women in this movie are great collectors of pseudonyms, so for simplicity’s sake, I’ll be crediting them all the way Trader Hornee itself does. That makes Jane “Elizabeth Monica” for our present purposes, although you won’t necessarily find her under that name in the credits for Sinner’s Blood or Count Yorga, Vampire.) The Hoosier Secret Service has just received a call from the Bank of the Wabash, the institution which holds the agency’s chronically overdrawn corporate checking account, but not to worry. Executive Vice President William Allen (Neal Henderson) isn’t calling to crack heads over the missing money, but to offer Hornee a way to bring the account back into the black. One of the bank’s biggest customers was industrialist Greg Matthews, a tycoon of the old school who liked to spend his spare time adventuring and pursuing a variety of scientific interests. Fifteen years ago, he, his wife, and their five-year-old daughter, Prentice, disappeared on an expedition into Africa, where they were searching for a legendary white gorilla called Nabuku. The two adults’ bodies were eventually recovered and decently buried, but no sign was ever found of the little girl. Matthews put some of his fortune in trust for Prentice at the Bank of the Wabash, which is how all of that comes to concern Hornee. The trust is due to mature this year, you see, and the dead man’s nearest living relatives would very much enjoy having access to the $40 million that it contains. But before Allen can hand it over, the bank’s rules require that the utmost effort be made to determine whether or not Prentice Matthews is really as dead as everyone assumes. With that in mind, Allen is authorized to offer the Hoosier Secret Service $10,000 plus expenses (and minus the amount of their current overdraft) for a journey into the jungle in search of the Matthews girl. Hornee agrees at once to accept the assignment.

Hornee and Sommers will have four companions on the trip, not counting any guides or bearers they might hire in Africa. Max Matthews (John Alderman, of Thar She Blows! and Black Samson) and his wife, Doris (Christine Murray, from Weekend with the Babysitter and The Affairs of Aphrodite), are the cousins who stand to inherit the trust if Prentice is proven deceased; it should be obvious enough why they want to come along. Tender Lee (Lisa Grant, of Lady Godiva Rides and The Undercover Scandals of Henry VIII) is a reporter for one of the big Indianapolis papers; she’ll be there as an outside observer to make sure everything stays on the up-and-up— and as Allen’s mistress, it’s only to be expected that the bank exec would favor her with an exclusive scoop from time to time. Dr. Stanley Livingstone (Fletcher Davies) is a naturalist from the Zoological Society founded on Matthews’s money; like Matthews himself, he hopes to discover the truth behind the legend of Nabuku. All of these hangers-on are introduced via sex scenes, Trader Hornee being the high-class film that it is.

The travelers’ first stop upon arriving in Africa is the villa of Carlin Carruthers Carstairs (Andrew Herbert, of Lust on the Orient Express), the British colonial commissioner for whatever territory this is supposed to be. He was the one who found the bodies of Matthews and his wife fifteen years ago, and he probably knows more than any other living white man about the way things are out in the countryside. Carstairs can’t say he thinks highly of the expedition’s chances. The region where the Matthews party disappeared is dominated by the savage and intensely xenophobic Meshpoka tribe, so he finds it impossible to believe that an unaccompanied child could have survived there fifteen minutes, let alone fifteen years. Nor can Carstairs imagine the girl having left any recognizable remains after all this time, given the local climate. As for Nabuku, it’s been a decade or more since the creature’s last reported sighting, so the commissioner figures Livingstone’s out of luck, too. No Prentice and no ape means no real point to the expedition, and thus no story for Lee to write up for her paper. But if Hornee and company are determined to waste their time, then the man they need to see is “Kenya” Adler (Brandon Duffy— whom fans of Orson Welles’s old Mercury Theater troupe might remember as Brainerd Duffield). Adler may be a drunken lout, but he’s hands down the best jungle guide in the business. The party will find him at the bar he owns, drinking up his own merchandise.

Now that the cast (including the inevitable squad of nameless native porters) is fully assembled, you’d think it was time for the adventure to commence. If fact, though, there’s surprisingly little active trekking through the jungle in Trader Hornee— or at any rate, it’s surprising until you remember that actively trekking though jungles costs money. Much more economical to shoot a few token trekking sequences, and then devote the bulk of our attention to what the characters get up to after settling down beside a lake to rest. For that matter, it’s also much easier to invent excuses to get the cast out of their own pants and into each other’s if everyone stays put— and if you’ve got a lake, then you’ve also got a ready-made excuse for a skinny-dipping scene or three. The one thing that might actually have been easier to do on the move is the running series of silly gags in which Nabuku (who, when we see him, makes the titular apes in The White Gorilla and White Pongo look like the work of Rick Baker) sneaks up to prank this or that member of the party. Eventually, though, the sexual frolics and lame attempts at cheap yuks are interrupted by an attack from the Meshpoka people, who chase off the porters and carry the whites away to their village. Once there, the warriors present the captives first to the tribal witch doctor (Ed Rogers), and then to Algona (Deek Sills), the ruler of the Meshpokas. Algona is the legendary White Goddess that Adler had just started talking about a few minutes before the big raid, so no points for guessing ahead of time that she’s really the long-missing Prentice Matthews. Strangely, Hornee, Sommers, Lee, Max, and Doris all figure that out for themselves long before they meet her, yet still act surprised when their individual audiences with the goddess confirm that supposition a piece at a time. (Do you need me to tell you that all but one of those individual audiences take a distinct turn for the sexual? No, I didn’t think so.) Some of the adventurers are spared as a result of their interviews with Algona, while others are condemned to fates even more horrible than those they would have suffered before. Oh— and the mystery of Nabuku is solved in a way that intersects with a last-minute subplot about a lost cache of Nazi gold.

Trader Hornee was originally an example of a phenomenon I mentioned recently in my Showgirls review, the self-imposed X-rating. Producer David Friedman had exhibited his movies on the adults-only circuit all through the 50’s and 60’s, so it stands to reason that he would stick to what he knew even after the advent of the rating system in 1968 introduced new possibilities. But as any modern viewer will quickly notice, Trader Hornee is an extremely tame sex movie by 1970’s standards, having only a bit of female pubic hair to set it apart from the adults-only fare of 1960. Perhaps as a consequence of that, Trader Hornee anticipated the Porno Chic phenomenon by a year or two, selling a significant share of its tickets to couples. When Friedman realized that guys were bringing their girlfriends to see this movie, he belatedly shipped a print off to the MPAA ratings board, and was granted an R-rating in return for a minor shortening and re-dubbing of the S&M session that introduces Max and Doris. Freed to play in mainstream theaters, Trader Hornee became one of Friedman’s biggest hits ever, grossing into seven figures on a $62,000 investment. And when Friedman entered into alliance with Something Weird Video some 20 years later, it became one of that company’s briskest sellers, too.

That, to me, is the astonishing thing about Trader Hornee, the timeless persistence of its success. I guess I can see how it would have had crossover appeal for a couples audience at a time when any and all cultural mores about sex were coming into question, since this movie is much less sleazy and sordid than most contemporary sexploitation fare. Like Charles Band’s forays into smut a few years later (Cinderella, Fairy Tales), it could even be described as innocent. Also, Trader Hornee shares with most Friedman productions a deceptively high level of production value. If nothing else, it looks like an actual movie, even when there’s nothing on the screen but a bunch of pasty schlubs with absolutely no muscle tone stripping off and telling corny jokes inside a tent pitched in some underutilized Southern California park. And as a final source of contemporary crossover appeal, let it be noted that Trader Hornee is not stingy with male nudity, even if there are no full Monties on display. Appreciators of athletic black men in particular should observe that Trader Hornee features one of the few tribes of exploitation movie savages in which the guys wear less clothing than the girls.

But what appeal, for any but the most hopelessly obsessed connoisseurs of obsolete titillation, can Trader Hornee possibly have today to account for its exalted position in the Something Weird catalog? Apart from the aforementioned parade of flawless ebony man-ass— none of which is presented in an overtly sexualized manner, I might add— this movie is a complete erotic washout. And its humor was already antiquated when the movie was brand new. The best joke is the recurring bit in which one character after another breaks the fourth wall for a moment to ask the camera if “Hornee” is really the detective’s name, but even it gets rerun once or twice too often. Otherwise, it’s nothing but moldy Borsht Belt leftovers, limp slapstick, and witless ethnic gags. With neither laughs nor sex appeal on offer, what the hell is driving Trader Hornee’s continued popularity? Is it possible that just that many people saw it during its surprisingly long years of theatrical circulation, and now wish to revisit it? Can porn nostalgia really be a commercially significant phenomenon?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact