Trader Horn (1931) ***˝

Trader Horn (1931) ***˝

Let me be completely honest with you. At least three quarters of the reason why I’m reviewing this movie is so that, one of these days, we’ll be able to discuss David Friedman’s Trader Hornee on an informed basis. That said, the original Trader Horn is well worth a look on its own merits. It is a damned effective jungle adventure movie (well… veldt adventure movie, technically speaking), especially considering what so often was allowed to pass for filmmaking— whatever the genre— in 1931. It has a few serious faults, particularly in the pacing department, but I can think of no other movie that draws so much attention to all the things the run-of-the-mill jungle flick does wrong, simply by conspicuously refraining from doing them.

The trader of the title is Aloysius Horn (silent Western star Harry Carey, who unlike so many of his contemporaries seems not to have been inconvenienced at all by the rise of the talkies), a rugged man in early middle age who has spent most of his adult life in the wilds of Africa. He claims to have been the first white man to see a great many of the Dark Continent’s more closely kept secrets, and whatever the truth of his boasts, he certainly has amassed a wealth of lore about the land, people, and wildlife. When we meet him, he is on his way up the Congo to trade for ivory with one of the jungle tribes, bringing with him a young Spaniard named Peru (Duncan Renaldo); this is Peru’s first foray into the African interior. Also along on the trip are about a dozen native guides and porters, led by Rencharo (Mutia Omoolu), Horn’s trusted companion of many years. As Horn’s men paddle the boat upriver, the trader fills Peru’s head with anecdotes about his career, together with the occasional tip on how to stay alive in one of the most untamed sectors of the globe.

When Horn, Peru, Recharo, and the rest reach their destination, the movie pauses for a bit to concentrate on the two favorite attractions of any antique jungle film: travelogue footage and bare-breasted tribeswomen. Once the plot gets rolling again, Horn sees his efforts at commerce disrupted by the arrival of a band of Maasai warriors. This is not Maasai territory— in fact, it’s most of the continent’s breadth away from the savanna people’s usual haunts— and Horn starts to wonder if the Maasai’s presence has anything to do with the greater than usual amount of tribal signal-drumming that’s been going on lately. Even Rencharo doesn’t seem to know what to make of it, but all the tribes in the Congo basin and the adjacent grasslands seem to be gearing up for something big, and whatever it is, it’s making them all less susceptible to the appeal of Horn and his wares. Horn decides that it would be a smart idea to get back on the boat and seek his fortune elsewhere shortly after the Maasai put in their appearance in the village.

That night, Horn and his followers have an encounter which the trader expects even less than his brush with the Maasai war party. Rencharo, standing watch, spies a column of footmen trekking through the forest under the leadership of a seemingly unarmed white woman. When Horn goes to investigate, he recognizes the woman as the missionary Edith Trent (Olive Carey, from Billy the Kid vs. Dracula). The Widow Trent first came to Africa nearly twenty years ago, making her almost as well acquainted with the place as Horn. On that initial venture, her husband was killed and her baby daughter abducted by raiders from an unknown tribe, and Edith has been combing the continent ever since in search of some clue to the girl’s fate. (This is not to say that she isn’t serious about her missionary work, you understand— it’s more a matter of Mrs. Trent having found a way to combine her two great goals in life.) As Edith excitedly tells Horn now, the reason she’s tromping around in the woods in the middle of the night is that she’s uncovered a solid lead at last, and she means to act on it before the trail goes cold again. Horn offers to accompany her for protection against whatever has the natives so riled up, but Mrs. Trent turns him down. She’d certainly value the aid of anybody with Horn’s track record, but her own comparably extensive experience indicates that a female missionary can often go where an armed man cannot. If she really has caught up with her lost Nina after all this time, then the last thing she wants to do is to jeopardize the reunion by waving a bunch of rifles around. Trent does, however, consent to have Horn and his party follow her at a discreet distance, giving her some firepower to fall back on in an emergency. She also extracts from Horn a promise to carry on the search in her place should she die without finding her missing daughter.

We all know what that means, don’t we? Sure enough, at the far end of as much wildlife footage as one human being can realistically be expected to withstand, Horn finds Edith lying dead at the foot of a mighty waterfall. It isn’t apparent whether her death was an accident incurred while scaling the falls or whether she was murdered by the increasingly restive natives. Horn, as good as his word, announces an immediate change of plan— the ivory can wait; he’s got a lost girl to track down. Peru, of course, made no such promise to anyone, so Horn doesn’t expect him to come along unless he really wants to for some reason. He does want to come, though, and the whole party is soon marching its way through yet more footage of exotic wildlife behaving exotically amid exotic landscapes, and occasionally killing one of Rencharo’s porters in exotic ways. That’s when the drums start up again, and the Horn party eventually finds itself surrounded at spear-point by a sizeable band of men, all of them decked out to the nines in their very best fucking-shit-up attire. Horn sensibly agrees to go wherever the warriors would like to take him.

Their destination turns out to be a fortified village (fortified in the sense of having a chest-high wooden rampart surrounding it), ruled over by just about the surliest chieftain you ever did see. The chief isn’t interested in Horn’s rum, or his salt, or even the clockwork music box he brought with him from Europe; he just stares the interlopers down from his throne, and orders the lot of them placed under guard in one of the huts. The last surviving bearer (and frankly, I’m not at all sure how the movie accounts for such attrition, since I sure as hell don’t remember that many animal-attack scenes) makes a break for safety, and gets crucified for his troubles. Again, Horn, Peru, and Rencharo have the good sense not to make a fuss. Horn does spend a lot of time looking out the windows, though, observing that more and more war parties keep filtering into the village, and that the warriors’ dress and equipment mark them as representing at least a dozen different tribes, some of them from as much as a thousand miles away. Obviously this must be connected to the signs of widespread military activity Horn has been seeing since setting off on the journey upstream, but who could wield so much authority over so many normally mutually antagonistic tribes? I mean, Isaac Hayes hasn’t even been born yet! Would you believe there’s a white jungle goddess in back of it all? And do I really need to tell you who that white jungle goddess is? The trouble, so far as the captives are concerned, is that Nina Trent (Edwina Booth) is no benevolent distaff Tarzan. She’s completely assimilated into the culture of whichever tribe it was that raised her, and she’s as fierce as any of the men in that continent-spanning army of hers. And despite Horn’s efforts to appeal to her sense of ethnic solidarity, she doesn’t give a rat’s ass that she and her captives have the same color skin. She may, however, care just a little that Peru is an extremely attractive man…

On the surface, Trader Horn doesn’t sound like anything special. It’s got the rugged Western adventurers, the faithful native sidekick, the beautiful white jungle goddess as a love interest for one of the heroes… and it has a staggering amount of wildlife footage, even by the standards of its genre. But what it also has is an immense amount of effort invested in it— the sort of effort that previously had been put forth only by maverick documentarians like Merrian C. Cooper. This was the first non-documentary Hollywood film to be shot on location in Africa, and director W. S. Van Dyke and his cast and crew went through hell to get it made. There were weather-related mishaps, plagues of insects, accidents (including two fatal ones), injuries, and weird tropical diseases, one of which would leave Edwina Booth periodically bedridden with life-threatening relapses for the next five years. Supposedly, she had to go to England to find a doctor who had any idea what her affliction was! You don’t subject yourself to more than a year of that sort of hardship (production on Trader Horn began as early as 1929, and it was originally conceived as a silent film) if all you mean to do is point the camera at a few monkeys and wildebeests and call it a day. Yes, there’s enough travelogue footage that the movie can get bogged down in places, but this is also some of the best black and white wildlife film I’ve ever seen. It’s thoughtfully composed throughout, and edited so crisply that the movie is not harmed in the slightest by the then-conventional absence of musical accompaniment; it’s shot at close enough range to subject the camera crew to some genuine danger; and it features enough different species to convey some distinct sense of the African veldt’s great biodiversity. In an era before the Discovery Channel— or even “Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom”— it must have been thrilling stuff. It’s also reasonably well integrated with the primary footage, even when the main cast isn’t really in the same place at the same time as the animals.

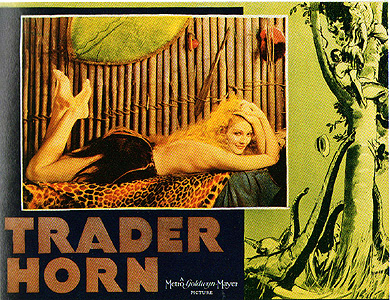

Less immediately obvious, but at least equally important, is the unusual even-handedness with which Trader Horn treats its Africans, and the virtually unique effort it makes to deal with the jungle goddess trope in a way that is not totally ridiculous. Don’t misunderstand me here. Trader Horn was made at the turn of the 1930’s, and the attitudes it reflects are by no means enlightened ones under today’s definitions. However, the Africans in this movie are at least played by real Africans— even Rencharo and the shaman (Riano Tindaman) who eventually comes forward as a rival for Nina’s power. The camera gawks at the native settlements Horn visits, but it does so while showing real people going about their ordinary business, rather than staged spectacles of invented barbarism. The vast bulk of Rencharo’s dialogue is delivered in whatever language Mutia Omootu spoke as his mother tongue, and even when speaking to Horn, he never stoops to the kind of pidgin English one usually hears from the mouths of “natives” in movies of this type. In short, while Trader Horn portrays African culture as primitive and alien, it nevertheless makes it plain that the African tribes do have culture. What’s more, it portrays individual Africans as possessing character and even virtue. The chief of the village where Nina assembles her army is not such a rube that Horn can impress him with his tacky little music box, for instance, and Rencharo frequently displays not merely courage and competence, but actual heroism. As for Nina, about the one concession Trader Horn makes to the expected formula for her character lies in her costume. Rather than dress as the African women do, she wears a sort of weird, shaggy skirt that looks as though it were made from several crinoline-like layers of horse hair, and an almost indescribable upper garment designed to make her appear topless when seen from behind. Otherwise, she’s pretty much one of the natives. She speaks their language— and no other. She accepts their cultural norms, and although she has led her adopted people to do something very unusual, raising a huge, multi-tribal army for the purpose of raiding on an unprecedented scale still makes sense within the framework of the lifestyle in which she was raised. The convention of the white savage probably could not be made any less silly than it is here, which is an astonishing thing to observe in a movie that was released decades before anyone particularly recognized that the idea was silly to begin with.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact