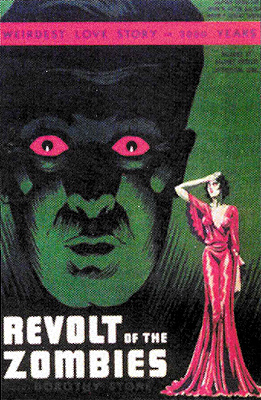

Revolt of the Zombies (1936) ½

Revolt of the Zombies (1936) ½

When Victor and Edward Halperin made their first horror film, 1932’s White Zombie, they both invented a subgenre and raised the bar for American horror movies to a level that only RKO was able to reach with any consistency for the next decade and a half. Their follow-up, Supernatural, was similarly groundbreaking in its own way, and was nearly as good. The third time, however, was the charm— if, by “charm,” we mean the black-headed pin jammed through the heart of a voodoo doll carved in the likeness of the Halperins’ reputation. In light of what its creators had done previously, Revolt of the Zombies is a shockingly bad film, and if you disregard what came before it, well, it’s still shockingly bad.

You might ask yourself how anyone could possibly make an unbearably boring movie about zombies that takes place in Cambodia, and features a number of scenes set in the majestic ruins of Angkor Wat. It’s a tall order, I grant you, but the Halperins have found a way: this time the zombies are merely a figure of speech, and Revolt of the Zombies doesn’t take place in Cambodia so much as it takes place in front of exceptionally obvious enlarged photographs of the place! I swear to you, watch this one and you won’t have felt so cheated since you first saw what that “prize” in the cereal box really looked like.

We start off, unexpectedly, along the Franco-Austrian front at the height of World War I. Among the advantages the colonial system held for the great powers was the occasional opportunity to make their downtrodden Third-World subjects do some of the dying for them in the event of a gigantic free-for-all meat-grinder of a war, and the French have imported a few units of Cambodian troops to pick up the slack on subsidiary fronts while they’re busy fighting for their lives against the Germans. Oddly enough, the Cambodians are not under the command of a soldier, but of a priest named Tsiang (William Crowell). According to Tsiang’s army interpreter, Armand Louque (Dean Jagger, who turned up many years later in X: The Unknown and many, many years later in Alligator), this is because the Cambodian soldiers are in fact zombies, created and controlled by a magical formula handed down from the ancient Khmer kings. General Duval (George Cleveland, of Flash Gordon and Night Key) doesn’t buy that for a second, but he changes his tune when what appears to be just a squad or two of Tsiang’s fearless and invulnerable soldiers capture an Austrian trench all by themselves. Duval does not react to this news with the pleasure that one might predict, however. No, he and his opposite number, General von Schelling (Adolph Millard… oh, and by the way— General von Schelling?!?!), are in agreement that Tsiang’s performance bodes very ill not just for the Central Powers, but for the whole of the white race, and they want to make sure that his formidable occult knowledge is never put to use again. With that in mind, Duval orders Tsiang imprisoned indefinitely in solitary confinement, but before the sentence can be carried out, Tsiang is murdered and an important-looking scroll of his stolen by von Schelling’s second in command, Colonel Mazovia (The Last Warning’s Roy D’Arcy). Mazovia tells no one about the killing, not even his boss.

With Tsiang dead at the hands of parties unknown, neither of the generals can be certain that the secret of zombie-making died with him, and Duval and von Schelling agree to collaborate on a most unorthodox project. Posing as civilian archeologists, they and their respective staffs will go to the ruined city of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, track down any information related to the creation of zombies, and destroy it before it can be used to upend the “natural” order of things. The nominal head of the expedition will be an expert on the Khmer named Professor Trevissant (E. Alyn Warren, from The Devil Doll and The Mask of Fu Manchu). Louque will be along to talk to the natives, and an old friend of his named Clifford Grayson (Robert Noland) will assist Trevissant in his endeavors. Finally, Duval’s daughter, Claire (Savage Fury’s Dorothy Stone), will come too— basically because Louque doesn’t have an obvious love-interest as yet, and we can’t allow that, now can we?

In a sane movie, the arrival of the team in Cambodia would trigger the start of a series of capers whereby Mazovia would try to exploit the talents of Trevissant, Louque, and Grayson to make sense of the magic ritual depicted on the silk scroll he stole from Tsiang, but sadly, Revolt of the Zombies is not a sane movie. Instead, it is the sort of film in which what we thought was going to be the plot is tossed ignominiously overboard to make room for a truly insufferable soap opera. Louque falls hopelessly in love with Claire, and she agrees to marry him, but in point of fact, the only reason Claire has expressed any interest in Armand at all is that she wants to make Clifford Grayson jealous enough to notice her. Once she has accomplished her mission, she cuts Louque loose and takes up with Grayson instead. It doesn’t take long to describe, but it sure does take a long fucking time to watch it happen. Afterward, there’s a scene in which Louque returns to Angkor Wat without Trevissant’s permission (the expedition had been chased away from the ruins by angry natives, but apparently there was no money in the budget for that, because we sure as hell never saw it), discovers the secret of the zombie ritual, and makes it back to the expedition’s new headquarters just in time to get bitched out by his boss and dismissed— before he has a chance to explain that he’s found the very thing they came to Cambodia for in the first place, naturally. In other words, Armand Louque has just been screwed over in rapid succession by the woman he loves, his best friend, and the man who controls his professional future, and he’s more than a little pissed about it. After an experiment with his faithful native sidekick, Buna (Teru Shimada, who went on to War of the Worlds and The Snow Creature), reveals that the zombie ritual really works, Louque sets about zombifying everybody he can get his hands on— Trevisant, General Duval, every porter, bearer, and guide in the camp— with the aim of carving out for himself a little penny-ante principality in the Cambodian jungle. He also uses his new powers to split up Clifford and Claire, but the one thing he can’t do is to make her love him for real. In a final, desperate gambit to win Claire’s affections, Louque renounces his wizardry, and frees all of his zombie slaves. But since Buna immediately leads a lynch mob of enraged ex-zombies to the villa out of which Louque has been operating to kill him, neither we nor Armand ever find out whether his final sacrifice had its intended effect.

I’m not sure I’ve ever been so happy that a movie was only an hour long. Seriously, I had no idea it was possible for me to get so bored in a mere 65 minutes. I suppose it’s mildly interesting that the character whom the movie initially sets up to be the hero turns out to be the principal villain instead, but apart from that, the only interesting thing about Revolt of the Zombies is the way in which it manages to fail in just about every possible respect. For one thing, this is an exceedingly chintzy-looking movie, displaying none of the Halperins’ customary care to conceal the limitations of their budget. The cheapness of the production couldn’t be helped, admittedly, but the set dressers might at least have made sure that the giant photos of Angkor Wat that serve as backdrops for much of the film lined up right. The casting department might have hired more than two extras to man the Austrian trench during the battle scene in the first act. Somebody might have checked to make sure that there were sound effects dubbed in at all the places that required them.

Turning our attention now to the less forgivable ways in which Revolt of the Zombies goes wrong, I’d like you to take a close look at the opening credits. If you do so, you’ll notice that evidently nobody wanted screen credit for writing the script! Honestly, I can’t say I blame Harold Higgins, Rollo Lloyd, or Victor Halperin; if I had written this crap, I wouldn’t want anyone to know about it either. In fact, I’d go a little further, and refuse directorial or production credit, too. There are so many scenes of people standing stock-still in front of a photographed backdrop, mouthing clumsy and insipid dialogue full of coagulating curds of lumpy exposition, that you’d swear this movie had been made in 1930 rather than 1936. The characters are so lifeless to begin with that it’s sometimes hard to tell whether or not they’re supposed to have been turned into Louque’s mindless slaves, and what’s worse, every single person in this movie is an asshole. It’s alright for Louque to be a simp who overcompensates his way gradually into evil; after all, he’s the bad guy. But after the cavalier way in which his so-called friends and colleagues jerk him around at every opportunity, I ended up spending most of the film in his corner anyway. Where he finally lost me wasn’t in bringing everyone who ever trusted him under his mental domination or in trying to establish himself as an independent Third-World strongman, but in his continued insistence upon pursuing Claire. “Armand!” I wanted to tell him, “Kick that scheming skank to the curb, and go find yourself some nice Fay Wray character to obsess over instead! The bitch ain’t worth it, man.”

Then, of course, there’s the big one: no fucking zombies. Oh, sure— they call them zombies, but except for one shot early on in which an Austrian soldier fires five bullets into one’s chest at point-blank range without seeming to bother it at all, there is no indication that we’re dealing with the walking dead here, and the remainder of the movie is quite explicit on the point that what we’re really looking at is simple mind control. To some extent the substitution makes sense, in that it does at least get around what would otherwise be the major difficulty that the ancient Khmer never practiced a religion that even dimly resembled Caribbean Voodoo, but I find it hard to believe that anybody, even in 1936, could have come out of this movie without feeling ripped off.

Compounding the sensation that you’ve been scammed are all the deliberate echoes of White Zombie that litter Revolt of the Zombies, as if its creators wanted to make absolutely certain everyone understood how good this movie wasn’t. Most conspicuous is the repeated reuse of the superimposed closeup on Bela Lugosi’s eyes which served as a visual shorthand for the exercise of Murder Legendre’s powers in White Zombie, and which performs the same function for Armand Louque here. What— were we not supposed to notice that Lugosi’s eyes look nothing at all like Dean Jagger’s? More important in the long run, though, is the way in which Revolt of the Zombies is built around the same basic conflict as the earlier film. In both cases, a man can’t win the woman he loves away from someone else, so he turns to occult power to force himself on her; the difference, of course, is that this time around, no effort whatsoever has been made to do anything of value with the material. There are few things a filmmaker can do to make me as grumpy as they can by taking the premise and plot structure from a movie I greatly enjoyed and using it as the basis of one that really blows. The proverb may have it that you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear, but with Revolt of the Zombies, the Halperins demonstrated that the reverse of that transformation is most assuredly within the realm of possibility.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact