The Red House (1947) **˝

The Red House (1947) **˝

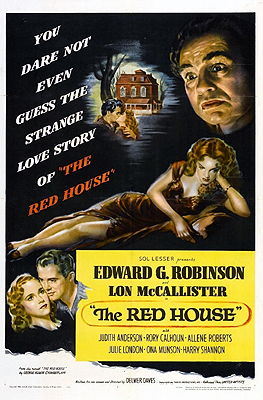

Something that I always find amusing about books on old-timey American horror movies is seeing how each author comes to grips with the period between 1947 and 1950, when there basically weren’t any. Will they skip straight from The Beast with Five Fingers to The Thing? Or will they interpose a short chapter in which Scared to Death and The Creeper implausibly find themselves the star attractions among a smattering of extremely marginal films? If it’s the latter, you can just about count on reading at least a few words about The Red House. An odd little vanity project for star Edward G. Robinson (who set up a whole indie production company with Sol Lesser in order to get it made), The Red House also comes up a lot in discussions of first-wave film noir, but just barely fits into that box, either. What this movie really is, although I can’t recall ever seeing it described as such, is a gothic mystery transplanted from Europe of the 16th-19th centuries to the modern rural United States, as if The Woman in White hitched a ride to California on the Joad family’s pickup truck.

That being so, the role of the haunted baronial castle will be played here by the sprawling farm of Pete Morgan (Robinson, whom we’ve seen before in Flesh and Fantasy and Soylent Green). Although Morgan is extremely prosperous by local standards, he has no interest in maximizing the economic productivity of his land. He doesn’t log his forest, he doesn’t breed his livestock for sale, and while his substantial liquid wealth would seem to require maintaining at least a field or two of some cash crop somewhere, the main focus of his farming activities is to provide for all his and his family’s needs from the work of his own hands. That’s because Pete zealously guards his privacy, which is difficult to do when your property is crawling with field hands, lumberjacks, and horse-traders. The irony, of course, is that by starving his neighbors of true gossip to spread about him, he leaves them irresistibly tempted to manufacture bullshit instead— especially bullshit concerning his spinster sister, Ellen (Judith Anderson, from The Ghost of Sierra de Cobre and Rebecca, whose presence in this cast suggests that somebody knew a gothic when they saw one), and his teenaged foster-daughter, Meg (Allene Roberts). The other problem with Morgan’s lifestyle of hardworking insularity is that he isn’t as young as he used to be, and he has a wooden leg. The latter handicap is a souvenir of a bad fall that Pete took about fifteen years ago, in those woods of his. Morgan is far too proud ever to admit this, but the farm is getting to be just too much work for him alone, and Ellen and Meg are in agreement that it’s time for him to take on a helper.

That’s where Nath Storm (Lon McCallister) comes in. Nath is one of Meg’s schoolmates, and arguably even a friend. Honestly, she’d like him to be considerably more than that, but he happens to be going steady with Tibby Rinton (Nabonga’s Julie London), the closest thing their little village has to a town floozy. But more importantly, Nath’s war-widowed mother (Ona Munson) has no head for business, and she’s just about finished running her late husband’s general store into the ground. The Storms are therefore always short of money, so it stands to reason that the boy would jump at a chance to put in some hours at the Morgan farm each day after school and on the weekends. That’s assuming, of course, that Pete’s womenfolk could prevail upon him to give Nath a chance. The old cuss makes a big show of putting up a fight, and tries to lowball the lad’s hourly wage at first, but eventually a deal is reached that satisfies everybody but Tibby, who immediately starts pouting over the prospect of no longer having her boyfriend at her beck and call. Going forward, she’s going to have a lot more patience for the attentions of horny post-adolescent lummox Teller (Rory Calhoun, from The Colossus of Rhodes and Motel Hell) than she has hitherto.

A funny thing happens after Nath’s first afternoon on the job, though. The boy stays for dinner with the Morgans, partly out of simple curiosity, and partly out of genuine desire to get to know his new employers on a personal level. There’s a storm brewing up by the time Nath is ready to set out for home, but rather than inconvenience the family by accepting Pete’s offer to lend him their pickup truck, he proposes to cut through the woods on foot. Not only will it halve the distance to his house, but the trees will give him shelter from the wind and the rain along the way. Pete flips out when he hears that, alternating reasonable objections (the paths are a deceptive maze; the only bridge over the creek that runs through the woods fell in ages ago) with bizarre ravings about “the screams” and “the Red House.” The superstitious quality of the latter warnings gets Nath’s teen machismo up, and he charges off toward the treeline despite Pete’s increasingly wild efforts to restrain him. The thing is, though… maybe Morgan was right? The paths really are so twisty and overgrown that it’s almost impossible to follow them at night. The bridge really is washed out, and the creek at that point is too swollen with runoff to ford safely. And eerily enough, Nath is half-convinced that he really does hear a screaming human voice concealed within the howling wind and all the other racket attendant upon the storm. Thoroughly spooked, he turns tail and sprints for the farm, where Pete welcomes him back with obvious relief, and Ellen sets him up for the night in one of the outbuildings.

Of course you realize that chickening out last night is only going to make Nath more determined to explore those woods— to master their labyrinth of trails, to settle once and for all whether or not he really heard voices screaming, and most of all to find this mysterious Red House of Pete’s. The next time he goes to work on the Morgan farm, he sets out early in order to traverse the forest by daylight, and to find thereby the most efficient route from one side to the other. Pete isn’t happy about that, and he says as much to Nath as soon as he realizes that the boy has arrived at the house from the wrong direction. Even so, Nath stubbornly retraces his steps through the woods on the way home that night— and this time, his orneriness has consequences more serious than a strange and retroactively embarrassing scare. While Nath is attempting to find the stepping stones across the creek in the dark, somebody creeps up behind him, and whacks him upside the shoulder blades with a great, big stick. Into the creek Nath goes, and then out of the woods again by the quickest route he can find. Given the circumstances, he understandably suspects Pete himself of being his unseen assailant, but in fact the man with the cudgel was Teller. As we learn the following morning, Morgan pays him handsomely to keep intruders out of his forest, sweetening the deal further with exclusive hunting rights to the territory. And when Pete realizes that Nath still isn’t done poking around in search of the Red House, he authorizes Teller to take sterner measures to dissuade him.

As that ought to imply, the Red House is no mere figment of a paranoid imagination, and the secrets it harbors are worthy of the Castle of Otranto. It would be most inconvenient for Pete, too, if those secrets ever got out to anyone not already privy to them. What Morgan has failed to anticipate, though, is that Nath would enlist both Tibby and Meg in his sleuthing. The Rinton girl is ultimately no threat, because she doesn’t really give a shit what might be out in those woods. She regards Morgan’s forest merely as an excellent place to get up to no good with her boyfriend, and she grows increasingly annoyed not only that Nath is actually serious about this Red House business, but also that he insists upon bringing Meg along on their Sunday-afternoon woods-scouring expeditions. Meg, however, is all in— not just because she recognizes how much closer the search is bringing her to Nath, but also because she finds something about the woods hauntingly familiar, even though Pete has forbidden her to enter them ever since she was a small child. The issue quickly becomes a point of weirdly violent contention between her and her foster father, until eventually Meg takes to exploring the forest on her own.

It’s on one of those solo forays that Meg at last finds what she and Nath have been looking for, and realizes in an eerie rush of clouded and fragmentary memories that she knows that overgrown, half-flooded ruin somehow. She doesn’t make much headway in puzzling out the connection, though, before Teller, mistaking her for Nath, starts taking potshots at her from a peak on the opposite side of the valley where the Red House lies hidden. Teller is shooting to scare rather than to kill, but the situation becomes genuinely life-threatening for Meg anyway when she slips while fleeing, and breaks her leg. Nath goes looking for her that evening, after he reports to the farm to find Pete and Ellen surprised and alarmed that the girl wasn’t with him, and locates her quickly enough that Dr. Byrne (Henry Shannon) is able to fix her up without an amputation like the one he had to perform on Morgan way back when. Pete feels little gratitude for the rescue, however. Blaming Nath for his foster daughter’s narrow escape, he fires him on the spot, and forbids the two kids to see each other in the future.

By then, of course, too many things are spinning out of control, in too many directions at once, for Morgan to have much chance of regaining his hold on any of them. Meg’s curiosity has been aroused to too high a pitch, and her foster father’s secrets have acquired too obvious a bearing on a past that she can’t quite remember remembering. Meg’s and Nath’s growing feelings for each other have passed the point at which the disapproval of a cantankerous old man can raise any obstacle against them. Nath has come too far and seen too much (or at least glimpsed it from the corner of his eye) to consider turning back now. Teller is getting increasingly trigger-happy, and Tibby is egging him on in ways she doesn’t understand. And most ominously of all, Pete is starting to have flashbacks to whatever past scandal or wrongdoing he’s trying to conceal. He frequently forgets himself, and calls Meg by some other girl’s name— and as her convalescence drags on, the way he looks at her feels ever less paternal. Ellen alone is in a position to assess all these developments at their true value, and she’s getting ready to take drastic action about them.

The only person I know who saw The Red House before I did found it intensely disappointing. The core of his objection seemed to be that he couldn’t figure out its most basic purpose or intent. “What the hell even is The Red House?” is a completely fair question, and the most correct answer strikes me as unlikely to appeal very widely. As I said earlier, the main plot is a gothic mystery uprooted from its native soil, but sometimes that plot gets stood on its head to adopt the form of a psychological thriller about a man cracking up under the weight of his own conscience. There are hints of a ghost story, too, implied by Nath’s first venture into the Morgan woods, but the movie has no intention whatsoever of making good on those. Then finally, haunting the periphery is the wraith of a film noir about a country girl driven by town ambitions, who falls in with a violent creep at the first sign that he might be able to help her bring them to fruition.

The Red House would be a markedly better film without its underdeveloped noir aspect. Tibby Rinton is never very persuasive as a femme fatale, not least because there’s never any serious prospect of her actually leading Nath astray. Indeed, the only reason why I interpret her as an attempt at noir’s most vivid archetype at all is because she’s made to look so much like 1947’s idea of a bad girl. Her seduction of and submission to Teller, moreover, is an irritating distraction from the much more compelling business of Nath and Meg unwittingly driving Pete mad by uncovering the secrets they never would have suspected him of having in the first place without his attention-getting efforts to keep them under wraps. I suppose there’s some potential interest in the fact that Tibby is fatale only to herself in the end, insofar as Teller was already on the road to ruin simply by virtue of his arrangement with Morgan, but The Red House would have to be their story for that upending of the expected noir psychosexual dynamic to elicit more than a “Huh. That’s odd…” This is so very much not their story, however, that Tibby could be excised from it altogether without requiring more than the subtlest rewriting of the rest of the film.

The more serious problem for The Red House is that it isn’t really anybody else’s story, either. That’s how the movie comes by the rest of its genre confusion, too. Writer/director Delmer Daves won’t commit to treating Pete as a tragic antihero whose obsession with covering up a long-ago crime lethally endangers the two people whom he loves most in the world, but neither will he allow Morgan to become a straightforward villain by focusing on Meg’s or Nath’s perspective. A fully Pete-centric version of the film would stand alongside Shadow of a Doubt as a precocious early example of the Portrait of a Psychopath template, but with the extraordinary variation of a psycho who plausibly yet mistakenly believes that he’s put madness and murder permanently behind him. Looking through Nath’s eyes the whole time, on the other hand, would give us a nifty gender-flip on the classic gothic premise of an innocent drawn by love into entanglement with a respected but degenerate family. And Meg as the viewpoint character would split the difference in all kinds of interesting ways. The Red House flirts with being all of these movies, and it undeniably does enjoy some of the benefits of each. Edward G. Robinson was by this point in his career an established expert at playing men driven to destruction by subconscious compulsions to wrongdoing, and he’s at or near his best here. You can see why Robinson wanted to make this movie badly enough to set the whole operation in motion himself. His young costars are no great shakes, to be sure, but Meg and Nath need the cornball earnestness that Allene Roberts and Lon McCallister bring to the parts, and it’s hard to find that packaged with actual ability in actors their age. Most of all, The Red House effectively conveys the impression that the events of its story are the worst things ever to happen in this sleepy little community, and that old folks are going to be talking luridly about them on each other’s front porches for decades to come. I just wish Daves had picked an angle and stuck with it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact