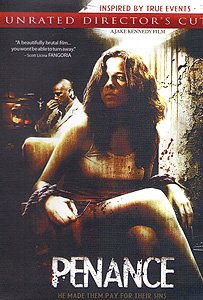

Penance (2009) **½

Penance (2009) **½

Admittedly, I’m an easy mark when it comes to any sort of transgressive horror, but Penance impressed me a little. I wasn’t expecting it to. Just reading the back cover of the DVD, you can practically hear writer/director/producer Jake Kennedy making his calculations. “The whole torture porn thing doesn’t seem to be going away any time soon,” he reckons, “and those movies are dirt cheap to shoot, right? Also, that found-footage trick they used in Cloverfield, Quarantine, and Diary of the Dead is really hot right now. So how about we make a found-footage torture porn flick? We can shoot in an abandoned building, we’ll go direct to DVD so that we don’t have to pay for more than one print, and we can use some of the money we save that way to hire a cult-horror C-lister and the no-talent relative of some big star to come in and give us one scene each, so that we can put a couple of recognizable names in the credits.” And in point of fact, the interview with Kennedy appended to the DVD confirms that that’s exactly how it was. It doesn’t give one a lot of hope for the film resulting from those calculations, and Penance does indeed have its share of serious problems. Its version of the found-footage conceit is without question the most nonsensical that I have ever seen. Tony Todd is even more completely wasted than usual (although his first appearance onscreen does make effectively unnerving use of his enormous size) in the role of the main villain’s chauffeur. Jason Connery’s epilogue scene is pure padding, serving no function except to nudge the running time far enough above 80 minutes to satisfy the modern definition of feature length— and even so, Penance would have been better off without it, as the epilogue’s action starkly underlines the absurdity of this footage ever being found in a form slightly resembling what we see. But at the same time, this movie has two very strong performances from actors I’ve never heard of in the key roles, and I found it unexpectedly thought-provoking. Mind you, I wasn’t thinking much about the things that Kennedy meant me to be thinking about (at least to judge from the most piously “significant” of the several thankfully unused alternate endings), but even a serious meditation on the state of horror cinema a decade into the 21st century represents a deeper post-viewing pondering than I would have imagined this movie able to inspire.

The central figure here is Amelia Wallis (Marieh Delfino, from Jeepers Creepers II), a young mother with a lot of expensive problems. To begin with, although this is never stated directly, it is implied that Amelia’s parenthood was far from deliberate, that her boyfriend (Automaton Transfusion’s Garrett Jones) is not the child’s father, and that Amelia and Will’s relationship has not yet progressed to the stage at which it would be reasonable to expect or to offer a pooling of economic resources. Amelia works at a battered women’s shelter, and while she finds her job extremely rewarding, she absolutely does not mean that in the financial sense. Hell, the shelter can’t even afford to grant its employees health insurance. That last is the real kick in the ass, too, because Amelia’s little girl was just diagnosed with incipient brain cancer. Asher is basically okay at the moment, but the moment won’t last long, and kiddie chemo costs more than Amelia makes in the average ever.

Luckily for Amelia, photogenic broke girls with baroque sob stories have an option in 2009 that their counterparts in previous eras lacked: reality television! We never find out the name or the premise of the show on which Amelia is angling for a spot, but we do learn that the gig pays $25,000, and that the application process involves the would-be participants essentially making a reality show of their own first, submitting an edited-highlights tape of a week in their lives. That’s right. Amelia’s audition tape is the first part of the movie’s cinema verite cover story, and it is precisely for that reason that the rest of the cover story becomes more implausible with each successive element of it that comes to light. Trust me, you’ll see what I mean.

Anyway, reality TV thrives on salaciousness and contrived drama, so it’s probably no accident that Amelia picks this week of all weeks to take some advice from her friend, Suzie Parker (Wicked Lake’s Eve Mauro), regarding a fun and easy way for a cute girl like her to turn a quick buck. Suzie, inevitably, is a freelance stripper, specializing in private parties (although she does take the occasional club booking during slow periods), and she’s evidently been nagging Amelia for ages to sign on as her partner for assignments requiring two dancers. Much of what Will films for the audition tape concerns Suzie’s imperfectly successful campaign to transform Amelia from a frumpy and slightly dour single mother into the sort of woman whose G-string men will eagerly stuff with dollar bills. Suzie herself is evidently satisfied with the results, though, because she soon has her friend taking over for her at a bachelor party where she was hired to perform. Amazingly, Amelia goes through with it even though she only narrowly escaped being raped by one of a different customer’s fouler friends (James Duval, from Evilution and Mod Fuck Explosion) a day or two before, when she tagged along to see what Suzie considers a typical day at the office. Undeterred by the camera pointed directly at his face, this fine specimen of manhood was prevented from launching his assault only by the intervention of the surprisingly formidable Suzie. That experience presumably gives Will even further reason for coming to see Amelia’s debut, his omnipresent video camera passed off to the customers as part of the training process for the newly hired “Gypsy.” In any case, the afternoon goes reasonably well (the customers are only moderately jerky, and no one tries to force himself on the entertainment), and Amelia walks away with $500— which is a hell of a lot more than I’ve ever made for one afternoon’s work. Nevertheless, she quite reasonably concludes that once was enough, and that “Gypsy” will be retiring the second Will drops that tape in the mail to the TV station.

Circumstance has other plans, however. The following evening, Suzie gets worked over by a customer even more formidable than she is, and Amelia is the first person she calls in the aftermath. This is not because she wants a shoulder to cry on or an emergency infusion of women’s activist rage to straighten out her head, though, regardless of how things might look at first glance. Suzie actually doesn’t care much about the black eye in and of itself. What she cares about is the two grand she’s going to lose out on tomorrow night, when she has to cancel a visit to a big-spending new client. Nobody wants to see a stripper with a puffy, purple eyeball (although there are a fair many bars toward the eastern end of Baltimore’s red light district where the dancers routinely sport even less appetizing disfigurements), and Suzie figures that if she can’t get the $2000, she might as well offer Amelia the chance to take her place. After all, “Sassy” could be anybody, so far as the customer is concerned. Amelia thinks that’s a terrible idea, and wants nothing whatsoever to do with it— except that $2000 is more than a month’s pay for her under normal circumstances. No, there was never really a chance that she wouldn’t cave eventually.

Thus it is that Amelia (accompanied once again by Will and his trusty camera, despite the obvious unlikelihood of someone willing to shell out $2000 for a stripper even considering consenting to that) finds herself climbing into a limo driven by Tony Todd (who can also be seen in Wishmaster and Final Destination)— a limo, I might add, with windows so thoroughly blacked out that the ones in the passenger compartment are opaque even from the inside. Not that that’s a harbinger of certain death, or anything… The journey ends at a huge institutional building that the intertitles at either end of the film identify as the Lichtenstein Hospital for the Criminally Insane, but that isn’t the only surprise that greets Amelia and Will. There are two other strippers already on the premises, and so far as Molly (Sita Young, of Bad Blood and The Last Resort) and Polly (Katherine Randolph, from Deadwater and The Story of O: Untold Pleasures) can figure, they’re each being paid an insane amount of money just to audition for some later, as yet unknown engagement. The orchestrator of all this weirdness is a middle-aged Englishman in an army uniform bearing a lieutenant general’s stars, whose several minions refer to him only as “the Great Man” (Graham McTavish). Those minions include a white-suited sleazebag who has “mafia” written all over him (Michael Rooker, from Slither and Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer); a dumpy, matronly blonde lady who would seem more at home in a second-grade classroom (Valorie Hubbard, of Flesh Eating Mothers and Resident Evil: Extinction); and a younger, dark-haired, foreign-accented woman who could have stepped right out of a New World Pictures chicks-in-chains movie (Alice Amter, from Exorcism and Mirror, Mirror IV: Reflection). In other words, this shit is looking creepier by the minute.

It gets worse rapidly from there. “The Great Man” takes little time to decide that all three girls meet his mysterious criteria, at which point it’s a round of drugged champagne for them and a bullet in the head for Will, courtesy of White Suit. The scenario here will be more than a little familiar to any of the dozen or so people who have seen The House of Whipcord; the Great Man and his followers have taken over this abandoned mental hospital for use as a reformatory for young women who are imperiling their eternal souls by partaking of the licentiousness of modern life. But rather than a retired judge, the head of this operation is a doctor— specifically, he’s Dr. Geeves Rahm, obstetrician-gynecologist. Evidently always a tad too religious for anyone’s good, Rahm was sent round the bend when he contracted AIDS from one of his patients, the latter woman not coincidentally a stripper by trade. Rahm considered his infection a sign from on high that he was supposed to spend the remainder of his truncated life redirecting sinners back onto the Path of Righteousness, and he’s developed an attitude toward sex that would make even Saint Paul say, “What the fuck, man? Seriously— lighten up!” And of the greatest importance for Molly, Polly, Amelia, and the unknown number of other girls who have fallen into his clutches, Rahm’s surgical training puts him in a position to combat temptation in ways that your average horror-movie religious fanatic can only dream about.

The implications of that training— which Penance does not shy away from in the slightest— are what got me thinking about the way horror films in general have been conducting themselves of late. We’re in a weird period in the genre’s history right now, with two starkly opposed sensibilities vying inconclusively for supremacy. On one side is the increasingly tame and bloodless school which goes far out of its way to avoid the stigma of an R-rating, even when it’s offering up an ostensible remake of a 1980’s slasher movie. Everything from The Covenant to Prom Night might be included in that category. On the other is the school that wants the hardest goddamned R it can get, and is perfectly willing to wallow hip-deep in graphically depicted suffering if that’s what it takes to get a rise out of its audience. House of 1000 Corpses, Hostel, and The Ordeal would all be good examples of the latter strain. There’s one thing both sets of films have in common, though, and it’s a rather surprising point of resemblance, all things considered. Even in the harshest and most torture-fixated of modern horror films, you almost never see anyone emerge from the story alive, but suffering from lasting injury; characters either make it through in one piece, or they don’t make it through at all. Penance, however, does not abide by that rule. The damage Rahm inflicts on Amelia is irreparable; however long she may live after making her getaway from Lichtenstein Hospital, she’s never going to get back what she lost. I suspect that’s going to make Penance a lot of enemies, especially among feminists, but this is one case where I think that says more about our prejudices than the filmmakers’. The offense that Penance commits in Rahm’s operating theater has nothing to do with reifying the patriarchy or abetting the “rape culture” (he’s the bad guy— they’re supposed to do evil things, remember?), and everything to do with breaking the most fundamental of all the unspoken agreements between consumers and producers of genre entertainment. In one short scene (which feels a lot longer than it really is), Jake Kennedy demolishes any possibility of an escapist relationship between us and his movie. Let me emphasize here that I felt it, too. When it became obvious what Rahm was going to do with that scalpel, and worse yet, that Kennedy was going to let him go through with it, my immediate response was approximately, “Aw, fuck— no fair!” I ask you, though: isn’t slavish devotion to the dictates of mere escapism one of the things for which we fans of movies made outside the system typically castigate Hollywood? We can’t have it both ways, and it would be dishonest to try, so I’m amending my “Aw, fuck— no fair!” to an “Aw, fuck— no fair! And good job, by the way.”

I just wish the rest of the movie were more worthy of that violation of expectations, or of the stellar acting work by Marieh Delfino and Graham McTavish. To begin with something I’ve already hinted at a couple of times, I can think of no other film in which the found-footage gimmick backfired so spectacularly. The object is to create a heightened sense of reality, but in Penance it achieves the exact opposite by making us constantly ask who is filming this stuff and why— and more often than not, the answers Kennedy gives us make the problem even worse. We start off with Amelia’s reality TV audition tape. Okay, I’ll buy that. I’ll also buy (albeit somewhat more reluctantly) that Will and Amelia would use the same tape to record their post-beating visit to Suzie’s house, with an eye toward documenting the incident for prosecution. One does have to ask, though, whether it’s occurred to any of these people that the evidence of Suzie’s assault won’t be very useful if it’s sitting in some TV producer’s office, or that Amelia’s TV audition won’t do her much good once it’s stashed away at the police station for use as Exhibit A in a criminal trial. What I refuse to accept is that Rahm would permit Will to bring that camera into his compound, that he would begin using it to document his own work after its original owner was dead, or that he would periodically hand it back over to Amelia so that she could film her various escape attempts! And lest you accuse me of being obtuse in assuming that Will’s camera, Amelia’s camera, and Pudgy Blonde’s camera are one and the same, let me call your attention to that epilogue I mentioned a while back, wherein a pair of detectives discuss the Lichtenstein Hospital case, and state explicitly that there’s only one tape in the evidence file. One tape means one camera, and one camera, in this context, means a colossal crock of shit. The saddest part is that if Jake Kennedy hadn’t been so inexplicably determined to have his own Diary of the Cloverfield Witch Quarantine, Penance’s most crippling defect need never have arisen at all.

There’s another major flaw that is inherent to the story, however, and it unfortunately also makes Penance a legitimate target for all the feminist rage that would have been misdirected if leveled at the surgery scene alone. I get that Kennedy made Amelia not a “real” stripper in order to keep her relatable, and in order to compound the horror of her situation by adding mistaken identity to the injustices heaped upon her. The thing is, though, that by harping on how Amelia isn’t “supposed” to be in Rahm’s insane reformatory, Kennedy implies that Molly, Polly, and the other girls are. I certainly don’t think he set out to do so, because Rahm is much too complete and convincing a villain for that, but it looks uncomfortably like an endorsement of the evil doctor’s basic assumptions about sexual morality whenever Kennedy draws the distinction between Amelia (whom Rahm and his people mistake for a sex worker) and her fellow prisoners (who genuinely do all the things their captors accuse them of). The point ought to be that no one should have to suffer through such an experience, and not just that good girls like Amelia don’t deserve this.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact