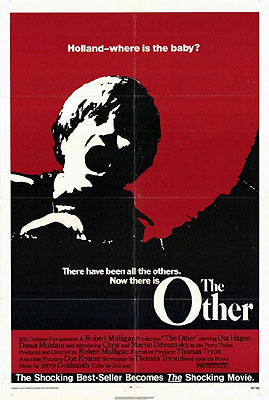

The Other (1972) ****½

The Other (1972) ****½

I don’t know what it is about evil child movies, but no matter how they may try, nobody seems to be able to make a really bad one. The Bad Seed and Village of the Damned are more or less universally acknowledged classics of the horror genre, and even The Good Son has its moments. Then, if we want to expand our definitions slightly, we might include The Exorcist, in which case we’re dealing with one of the really heavy hitters. There are more out there, of course, for those who want to dig deeper. And I would strongly suggest that anyone who well understands the pleasures of an uncommonly good horror movie do just that, because despite its comparative obscurity, The Other is among the best of the bunch.

To begin with, it has a highly unusual setting: rural New England in the mid-1930’s. Not a lot of horror movies are set in those days, not even ones that were made in those days. The bucolic milieu offers especially fertile ground for what is sometimes referred to as “sunlit horror”— that is to say, horror that does not rely on creepy atmosphere, inherently eerie places, the darkness of night, or any of the other commonplaces of the genre. It’s a very demanding approach, and when it goes awry, it often strays lethally into tedium, rather than committing the more forgivable sin of ridiculousness. But when it’s done right, it is all the more effective. The makers of The Other did it right. Then there’s the issue of casting. Unless you count Uta Hagen, who was a stage actress first and foremost, there isn’t a single notable star in this movie. With nothing but unknowns in the cast, there is much less disbelief to suspend— you’ve never seen any of these people before, so you have no reason to think of them as anybody other than the characters they’re playing here. That’s an important asset in this case, because The Other places so much emphasis on the tangled and sinister relationships between its characters.

The film’s one serious misstep occurs right at the beginning, when we are first introduced to Niles and Holland Perry (Chris and Martin Udvarnoky). The good twin-bad twin dichotomy is apparent even before either character opens his mouth; all we need to see is the expression of excessive earnestness on Niles’s face, and the wary look in Holland’s shifty little eyes, and we instantly know which is which. The boys are playing soldier, and Holland leads his brother on a raid into their neighbor’s barn with the object of pilfering some preserves. Holland breaks one of the jars while trying to remove it from its storage cabinet, and the sound brings Mrs. Rowe (Portia Nelson), the owner of the barn, rushing over to see what’s going on. Mrs. Rowe catches Niles as he flees the scene of the crime, and taking him for the mischievous Holland, begins whaling on him with her rug beater; Niles’s protestations that she’s got the wrong boy avail him nothing. Here again, the movie has tipped its hand, at least where an experienced viewer is concerned. It is immediately obvious that Holland is never in the same shot as Niles, that the former boy never appears onscreen at all as long as Mrs. Rowe remains in the frame, and that he emerges from hiding the moment the woman is gone. To anyone with a solid background in horror movies, this is a strong hint that there is no Holland Perry, that the bad twin is merely the alter ego of the good. What saves The Other from this opening burst of incontinence is the fact that, when it is at last made explicit, this revelation, in and of itself, is not the movie’s punch line.

But before we go too far down that path, we need to be introduced to the rest of the characters. Niles and Holland live with their Aunt Vee (Norma Connolly) and Uncle George (Lou Frizzell, from House of Evil and Devil Dog: The Hound of Hell); their pregnant, 20-odd-year-old sister, Winnie (Terror in the Sky’s Loretta Leversee), and her husband, Rider (John Ritter, whom you’re most likely to remember from Bride of Chucky); and their Russian immigrant grandmother, Ada (Uta Hagen, who was also in The Boys from Brazil). The boys’ father is dead, and their mother, Alexandra (Diana Muldaur, from Chosen Survivors and Planet Earth), has apparently spent most of the past year in a mental hospital, for reasons that will only gradually be revealed. In addition, a man named Angelini (Victor French, from The House on Skull Mountain), and a boy named Russell (Clarence Crow) can usually be found hanging around the Perry household. Angelini is a hired hand on the Perry farm, while Russell is some sort of cousin, though the precise nature of his relationship to the boys is not clear.

What is clear is that Holland (or the aspect of Niles’s personality that manifests itself as Holland) doesn’t like Russell. So when Russell dies in a freak accident, impaling himself on a pitchfork concealed in a hay bale, only the rankest of neophytes in the audience will fail to suspect that there is more going on than meets the eye. For not only have we seen reason to believe that Holland is really his “brother’s” out-of-control id, we also know that Niles is a truly exceptional child. At the core of his unusually close relationship with Grandma Ada is something that the boy refers to as “the Great Game.” This “game” is nothing short of astral projection, a psychic power Niles and his grandmother share, and which Ada has taught him to use with considerable skill. Niles can literally enter the mind of any living thing he sees, and experience the world through its senses. Mostly Niles plays the Great Game with animals, but as is revealed when he uses his powers to discover the secret of a carnival magician’s disappearing act, it works on humans as well.

Holland gets up to his old tricks again a few days later. The afternoon after Ada tells Niles that Holland needs to apologize to Mrs. Rowe for trying to steal her preserves (another oblique hint that Holland isn’t quite real— otherwise, why wouldn’t Ada just tell Holland directly?), he goes to the old lady’s house dressed as a stereotypical sideshow magician. After he offers the required apology, he gets Mrs. Rowe to let him into the house so that he can show her his magic act. Holland climaxes the show by pulling out of his hat not a rabbit, but a very large rat, and Mrs. Rowe, who has an extreme phobia of rats, drops dead of a heart attack right in her parlor. No one finds her body until many days later, when the stench starts attracting the neighbors’ attention.

Then Alexandra comes home from the hospital, and the pieces finally start falling into place, as we begin seeing indications of exactly how dark the secrets of the Perry family really are. Much of the mystery revolves around the relationships between Niles, Holland, and their parents. Niles’s most prized possession is a signet ring which once belonged to his father. As he spends so much time assuring himself, Niles was given this ring by Holland, who, as the older of the two twins (by 20 minutes, or so Niles says), is the rightful heir. But something is clearly amiss with this situation, because both boys frequently point out that the ring is “supposed to be buried.” For this reason, Niles never wears the ring, keeping it instead in a tin can concealed in his dresser, a hiding place it shares with another small object which is always wrapped tightly in a piece of bright blue cloth. It is shortly after Alexandra’s return that we get a look at what this parcel contains: the last two joints of a human finger! And when Niles’s mother discovers the can and its contents, the skeletons begin sneaking out of the closet in earnest. It seems Niles’s father died in a fall down the stairs to the root cellar beneath the barn, and given what we know about Holland, it’s hard not to wonder if maybe it wasn’t really an accident. Alexandra confronts Niles about his secret keepsakes one evening, and the scene rapidly turns ugly. But the really strange thing is the look of horror that passes across Alexandra’s face when Niles answers her demand to know when Holland gave him the signet ring by saying it happened shortly after their birthday. In light of everything else we’ve already seen, that look has far more impact than Alexandra’s paralyzing fall from the front porch, to which Holland pushes her when she refuses to surrender the ring and the finger. (This is the only time both boys are ever in a scene together when an adult is around.)

So what’s really going on here? Well to begin with, we are of course mostly right in surmising that there is no Holland Perry. There is no Holland now, but there used to be. He was indeed Niles’s slightly older identical twin, and he did indeed have a pronounced affinity for trouble, but he fell down a well and died on his birthday a few months before The Other’s story picks up. It was the shock of this tragedy, coming so soon after the death of her husband, that sent Alexandra to the mental ward. So if Holland died on his birthday, after his father had already had his maybe-not-so-accidental fatal fall, how do you figure Niles came to possess the signet ring? And whom might that mummified finger have belonged to?

But the nastiness has only begun. In light of my long-established policy of not blabbing too much about plot twists when a top-notch movie comes along, I’m not going to go into detail, but I will say this much: Holland may be dead, but that doesn’t necessarily mean he’s gone, especially when he and his twin brother are both powerful psychics. I’d also like to remind you that Winnie’s got a baby on the way, and to suggest to you that sibling rivalry might be transferable to the next generation. The note on which The Other ends is evil in a way that only the conclusions of 70’s movies can be. This one’s going to stick with you.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact