Orloff and the Invisible Man / Orloff Against the Invisible Man / Orloff Against the Invisible Dead / The Invisible Dead / Dr. Orloff’s Invisible Monster / Love Life of the Invisible Man / Secret Love Life of the Invisible Man / La Vie Amoureuse de l’Homme Invisible (1970) -**

Orloff and the Invisible Man / Orloff Against the Invisible Man / Orloff Against the Invisible Dead / The Invisible Dead / Dr. Orloff’s Invisible Monster / Love Life of the Invisible Man / Secret Love Life of the Invisible Man / La Vie Amoureuse de l’Homme Invisible (1970) -**

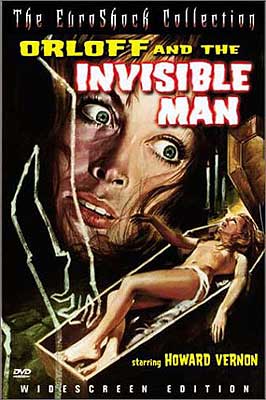

Dr. Orloff might be Jesus Franco’s signature horror movie villain, but the character was not original to him. Franco lifted Orloff from the early British Edgar Wallace adaptation, The Human Monster, crossed him with Eyes Without a Face’s Dr. Genesier, and then spent the rest of his career tinkering with the characterization. So it’s rather appropriate that somebody else would eventually swipe Dr. Orloff from Franco. The somebody in question was another Eurocine regular by the name of Pierre Chevalier. His Orloff movie, released in 1970, goes by a bewildering variety of titles, a few of them readily susceptible to confusion with this or that Franco Orloff movie, and none of them clearly favored over the others by theatrical distributors or video labels. Thus the first challenge of this review was to decide what I was even going to call the movie. Orloff and the Invisible Man may lack the zing of the other titles, but it has the advantage of more or less accurately reflecting the content of the film, without inviting mix-ups between it and Dr. Orloff’s Monster.

There’s a new physician in whatever middle-of-nowhere generic Euro-village this is supposed to be, a certain Dr. Garondet (Paco Valladares). Not being from around here, Garondet doesn’t think anything of it when a young boy arrives on his doorstep with a message that there’s a patient urgently requiring his services up at the castle of Professor Orloff (Howard Vernon, from Seven Women for Satan and Zombie Lake). Imagine his surprise when his own maid refuses the messenger entry; when no one at the local tavern will agree to drive him to the castle except at the most extortionate rate; when the coachman who does take the job contrives to leave him stranded by the side of the road before the castle so much as comes into view; and when even the professor’s servants obstinately refuse to cooperate with Garondet’s efforts to speak to their master. In the end, Garondet is left to blunder about the castle alone on just the vaguest of tips from the maid (Evane Hanska) until he finally makes contact with Orloff’s daughter, Cecile (Brigitte Carva). The doctor is not amused by what he learns from Cecile at the end of his frustrating journey— there’s no one sick at the castle at all. Cecile merely told him there was because she could think of no other way to get Garondet to stop by. Garondet is right there with you in wondering what the fuck Cecile wanted from him if nobody was ill, but the girl has reasons that almost make sense if you take a step back and squint at them in very low light. She wants somebody to persuade her father to give up his latest research project, which she characterizes as abominable, unnatural, and demonic. Cecile knows she can’t do it herself, and she figured maybe another doctor could penetrate her dad’s obsessive stubbornness.

Dr. Orloff is annoyed at first to see Garondet when Cecile shows him to the laboratory, but eventually the opportunity to talk about his work with someone who might possibly understand it wins out. Orloff has created what he bills as the perfect man, a humanoid creature superior to ordinary humans in every way both mental and physical. And in case that weren’t enough, Orloff’s Übermensch is also invisible. Garondet is understandably skeptical, but there’s no gainsaying the objects that move about the lab in response to Orloff’s commands, just as if something he couldn’t see were manipulating them. The younger doctor is thrown for a second loop, too, when Orloff explains the rationale behind this extraordinary work. Ultimately, he intends to build a whole race of these invisible creatures, “to rule mankind and dominate the world.” I’m honestly not clear on whether Orloff means that his creatures will enable him to rule and dominate, or if he intends his synthetic Herrenvolk to do the ruling and dominating on their own.

Obviously Garondet is curious about how his less than willing host got into the monster-making business in the first place, so Orloff obliges him with a long, boring, rambling story (accompanied by a long, boring, rambling flashback) that never once addresses the question! Instead, Orloff tells the other doctor about the cataleptic episode that left his daughter incurably insane. Note that this is both the first and the last we’ll ever hear of Cecile’s supposed mental malady. Certainly no one seems to have told Brigitte Carva that she was playing a hopeless lunatic. Anyway, the girl was once mistakenly pronounced dead and interred in the family crypt. But two of the servants, Maria the housekeeper (Isabel del Rio) and Raymond the gamekeeper (Fernando Sancho, from Swamp of the Ravens and The Carpet of Horror), conspired to rob Cecile’s coffin for the jewels she was wearing. Raymond had been in unrequited love with Maria, you see, while she was perfectly willing to trade her affections for a fortune in stolen property. Cecile regained consciousness while Raymond was tugging on a tight-fitting ring, however, and despite the derangement of her mind, she remained lucid enough to finger him as the burglar. Raymond in turn rolled on Maria, but it’s a tough call which of the conspirators got the worst of their master’s vengeance. Orloff set his hunting hounds on Maria, while Raymond has languished in the castle’s dungeon ever since, feeding the invisible creature with his blood.

Now that Orloff has explained himself (or not…), he has some questions for Garondet. Specifically, he wants to know who the hell let him into the castle. Not really thinking about where this might be leading, Garondet admits that he buffaloed his way past the groundskeeper (Eugene Berthier) and played upon the maid’s sympathies for her mistress. When he hears that, Orloff summons the servant girl to the lab, and promptly hands her over to the invisible man-thing for a disciplinary rape. Garondet is horrified, but he maybe should have arrived at that sentiment sooner. Now that the younger doctor knows all of his secrets, Orloff has determined that Garondet must never again leave the castle alive.

The whole time I was watching Orloff and the Invisible Man, I kept repeating to myself the same question: what could possibly possess anyone to rip off Jesus Franco? Because it isn’t just the name of the title character, or the casting of Howard Vernon in the role. Orloff and the Invisible Man really does ape an astonishing array of typical Franco-isms, from the intrusive zoom lens to the prominent pointless flashback to the score that sounds by turns like a pastiche of Daniel White in all of his various composing modes. It has the sex-crazed monster, the overwhelming mass of gratuitous nudity, and the tendency to lose the thread of the story completely whenever a pretty girl takes off her clothes. When the invisible creature’s form is revealed at last, I think you’ll agree that it belongs in some second sequel to Two Undercover Angels at least as much as it belongs in any gothic mad science movie. Hell, Orloff and the Invisible Man even copies the most… let’s call it personal… of Franco’s idiosyncrasies by casting the shaggiest-crotched young actress in the land as the female lead. (Seriously, Brigitte Carva looks like she’s wearing the gag merkin from In the Sign of the Taurus.) All Pierre Chevalier is missing— and this is indeed a serious oversight— is a nightclub scene. I had always been under the impression that Franco got as many gigs as he did simply because he worked faster and cheaper than anybody else, and that only at the turn of the century, more or less, did he start getting treated as a filmmaker worthy of attention, positive or negative. But if Eurocine hired Chevalier to make them a movie in what is incontrovertibly the Franco style, then maybe he had a conscious cult following in Continental Europe already by 1970. Otherwise, I’m powerless to explain how or why Orloff and the Invisible Man exists.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact