Mutant (1984) **

Mutant (1984) **

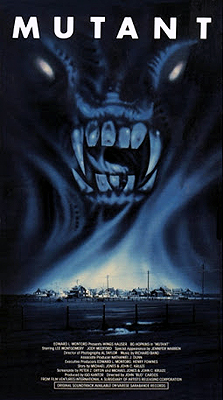

Screenwriters John C. Kruize, Michael Jones, and Peter Z. Orton wanted to call it The Pestilence. Director Bud Cardos wanted to call it Night Shadows. Film Ventures International, the also-ran schlock-peddlers who released it to American theaters, called it Mutant. Whatever you want to call it, though, this movie is certain to disappoint you. It exists in that grim entertainment wasteland where technical adequacy meets nigh-total lack of originality or inspiration, neither good enough nor bad enough to reward the 99 minutes that it asks of you. And if you rented Mutant on VHS, like I kept almost doing throughout the second half of the 1980’s, then you got suckered in by one of the truly great Damned Dirty Lie box covers of the era. Despite the promise of that fanged, phantasmal monster looming out of the clouds overhead, Mutant is at heart something closer to a zombie movie. It’s a bit like The Children, only without (except in one scene, which we’ll talk about later) the unique frisson that comes from turning little kids into killing machines.

Along with being zombie-adjacent, Mutant plays both the eco-horror and backwoods horror cards. On former front, it sets the action in Goodland, a fictional tiny town in the Deep South where a chemical company by the ominous name of New Era Industries is running amok dumping gluppity-glup and schloppity-schlop down the shafts of the played-out mine that supported the local economy in days gone by. That, of course, is what’s turning the townspeople zombie-like, but at the outset, the handful of locals whom we hear from on the subject think they’ve just got a nasty little flu outbreak on their hands. And on the backwoods horror side, Mutant gives us as our initial viewpoint characters 20-something big-city douchebag Josh Cameron (Wings Hauser, of The Wind and Beastmaster 2: Through the Portal of Time) and his brother, Mike (Lee Montgomery, the little boy from Burnt Offerings and Dead of Night all grown up), who wind up in Goodland when their rustic vacation runs them afoul of a gang of malevolent rednecks led by one Albert Hogue (Marc Clement, of King Kong Lives). The dude-bros also manage to get on the bad side of Sheriff Will Stewart (Bo Hopkins, from Tentacles and Sweet Sixteen), partly due to an altercation with Albert and his followers at the local watering hole, but mainly because Stewart takes them for troublemakers after Mike says that he and his brother found a man dead in the alley beside the railroad tracks, but the only person to be found at the scene a few minutes later is a passed-out drunk. Just the same, though, Stewart is serious enough about doing his job in a non-prejudiced manner to notice the puddle of yellow slime on the ground not far from where the drunk was lying, and to gather some up so that town physician Dr. Myra Tate (Jennifer Warren, of Shark Kill and The Intruder Within) can have a look at it. Then Stewart drops the Cameron brothers off at the boarding house run by old Mrs. Mapes (Nell Santacroce, from The Legend of Blood Mountain and the 90’s made-for-TV Night of the Hunter) with stern orders to get the fuck out of Goodland first thing in the morning.

It’s at the boarding house that Josh and Mike get directly into zombie trouble— which you’ll be pretty much expecting, since the same house figures in a pre-credits prologue about an investigator from the Environmental Protection Agency (Charles Franzen) getting ambushed by a sort-of-living sort-of-dead girl (Pat Moss). There are two surprises here, though. First, it’s Mike, despite seeming up to then like he’s on track to become one of the earliest Final Boys, who falls victim during the night, leaving obvious monster-bait Josh to take over as solo core protagonist. And second, Mike doesn’t even need to be lured outside on some flimsy pretext in order to get whacked. The zombie chick from the proloque pops out of a trapdoor concealed beneath the bed where Mrs. Mapes put him up, and drags him down to the cellar, never to be seen alive again. The old lady claims not to know where Mike got off to when Josh asks about him in the morning, saying he was up and away before she got out of bed herself. Mrs. Mapes also notes disapprovingly that wherever the missing kid went, he left last night’s clothes heaped on the bedroom floor when he split.

Josh’s efforts to locate his brother lead him into contact with elementary school teacher and sometime bartender Holly Pierce (Chained Heat’s Jody Medford), niece of the eponymous proprietor of Jack’s Tavern (Danny Nelson, from Vicious Kiss and Blood Salvage). Uncle Jack is one of the many Goodlanders laid up with the weird toxic waste sickness, but not yet running around under cover of darkness smearing caustic ichor all over people from the perpetually weeping lesions in their palms. Since the school is shut down due to mass absenteeism among staff and students alike, and since nobody but Josh has come into the bar all day, Holly agrees to help him look for Mike. Meanwhile, Dr. Tate makes the astounding discovery that Sheriff Stewart’s scum sample started out as human blood, which gets the both of them thinking about that flu everyone seems to be catching lately. Stewart’s efforts to enlist aid from the regular police department initially come to naught, however, because Captain Thomas Dawson (Johnny Popwell, slightly more visible here than he was in either Deliverance or The Visitor) has too many other problems to spare the manpower for something that shouldn’t normally be police business anyway.

Josh and Stewart cross paths again after a second clash between Cameron and Albert Hogue, this one in the basement of Holly’s school, where Hogue works as the janitor. The two men had more or less simultaneously found the body of a child who had succumbed to the New Era disease, and Albert tried to lynch Josh for “murdering” her. Having failed in that, Hogue tries to frame Cameron to the sheriff, but Stewart is perceptive enough to recognize that that little girl wasn’t killed by any man. Over the next twelve hours or so, Cameron, Stewart, Holly, Tate, and even that asshole Hogue will find themselves further and further in over their heads, as Goodland depopulates, zombies proliferate, and a team of fixers from New Era Industries try to cover up the company’s malfeasance.

I want to go back for a moment to Mutant’s opening scene, because it serves as a weirdly apt meta-commentary on the film itself. The EPA man who gets killed by Mrs. Mapes’s undead daughter is never identified as such until after almost everyone watching will have forgotten that he was ever in the picture to begin with. It’s not remotely apparent in the moment why he’s snooping around somebody’s property in the middle of the night, nor is it at all obvious what he’s up to when he scrapes that blob of viscous yellow crud from the lawn. We don’t get a good look at the zombie girl, either, so all we can say for certain by the end of the scene is that there’s a basically humanoid monster on the loose, and that its touch inflicts deadly chemical burns. To all appearances, then, this scene is simply Mutant’s take on the old routine of grabbing the audience up front with a decontextualized shock. That was one of the key narrative techniques of 1980’s horror cinema, and there’d be nothing in the world wrong with using it here if that were all the filmmakers were trying to do. But in fact this prologue was designed to accomplish something altogether different, as you’ll realize about two thirds of the running time later, when circumstances suddenly goad you to think, “EPA man? Wait— you mean that guy? Was he supposed to from the EPA?” Far from a mere suspense setup, Mutant’s prologue was intended as crucial foreshadowing of the true threat lurking in Goodland. But the meanings of its characters and events are left so obscure that the purpose of the scene itself is obscured right along with them. Instead of foreshadowing toxic zombies, an evil corporation, and maniacal rednecks, it foreshadows how Mutant is going to fall on its face just about every time it attempts to do anything more sophisticated than a straight run-through of the standard 80’s zombie-movie plot.

Indeed, Mutant’s core problem is that it won’t just settle down to be a basically adequate meat-and-potatoes programmer. It wastes entirely too much time contriving an air of mystery around New Era Industries, considering that the firm ultimately serves no purpose but to be the polluters whose malign negligence set the Goodland zombie plague in motion. We spend entirely too much time with Albert Hogue in light of his marginal impact on the main story. The second-act subplot about Josh becoming a fugitive is completely fucking pointless, since Stewart never seriously considers him a suspect in the basement girl’s death— or at any rate, not after the sheriff sees the body for himself. And it seems downright gratuitous to trap the Cameron brothers in Goodland with a car wreck (courtesy of their first encounter with Hogue and the gang), only to have Mike’s disappearance supply a far stronger reason for Josh to stick around a short while later. All these extraneous ramifications mean that Mutant feels like it’s running around in circles for most of the running time, searching frantically for its own narrative through-line.

At the same time, though, there’s a sufficiently high standard of fit and finish here to keep Mutant from ever becoming a real stinker, both for better and for worse. The movie never looks cheap in ways that can’t be excused by its economically depressed setting. The various locales all plausibly pass for whatever they’re supposed to be, regardless of whether they were constructed sets or found locations. The gore effects are good enough to pass muster in the era of Tom Savini and Rob Bottin, even if they would certainly never be mistaken for either of those masters’ work. Even the crudely simple monster makeup (not much more than black and white greasepaint applied with a starkness better suited to the stage than to a movie screen) is strangely evocative, whether or not it would meet any defensible standard of “good.” On the one hand, all that basic competence protects Mutant from being written off as garbage, but it prevents it from being enjoyed as garbage, too.

There is one sequence, though, in which everything comes together, and Mutant briefly becomes, if not the movie I wanted it to be, then at least one that I’d have been happy to settle for. As I said at the beginning of the review, Mutant’s premise is awfully close to that of The Children, what with its rural settlement beset by quasi-undead creatures with burning hands, but it lacks both that movie’s clarity of purpose and the raw nastiness that comes with making the monsters a bunch of little kids. Well, toward the end of Mutant, Josh and Holly wind up back at the school, where they face off against all the students who’ve been home sick this past week or so. At that point, we are exactly back on The Children’s turf, and the ramp-up in Mutant’s effectiveness is extraordinary. Granted, the other movie does it better for a variety of reasons even here, but there’s simply no gainsaying the inherent horrific power of a kill-or-be-killed situation in which the threat is a bunch of fourth-graders.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact