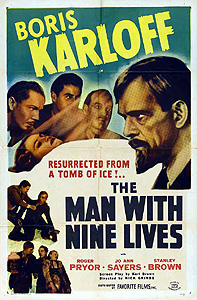

The Man with Nine Lives/Behind the Door (1940) ***

The Man with Nine Lives/Behind the Door (1940) ***

Most people either get a premise right the first time, or they never get it right at all, especially when much of the premise in question was borrowed from somebody else in the first place. That wasn’t how it worked with Columbia Pictures’ early-40’s mad doctor movies, however. The Man They Could Not Hang was a decent enough time-waster, but nothing at all more than that. Yet The Man with Nine Lives, the first of several follow-up films, represents a significant improvement over its predecessor, and might reasonably be described as the movie director Nick Grindé and screenwriter Karl Brown ought to have made originally.

It’s going to be a while this time before we get around to meeting Boris Karloff. Instead, the doctor we’re introduced to in the opening scene is Tim Mason (Scared Stiff’s Roger Pryor, returning like about two thirds of this cast from The Man They Could Not Hang), a leader in the developing field of “frozen therapy.” You can think of it as a very primitive form of cryogenics, although the applications Mason sees for it are rather broader than to freeze Walt Disney until such time as medical science devises a cure for whatever ails him. In particular, Mason sees in frozen therapy a potential cure for cancer— one which rather astonishingly works according to much the same principle as modern chemotherapy, even though chemotherapy wouldn’t begin to be developed for another four years or so when The Man with Nine Lives was made. Mason’s research indicates that healthy tissues are more resistant to the rigors of extreme cold than cancerous tumors, so that by placing the patient in a cryogenic coma for a few days, he can temporarily arrest the spread of the disease. He thinks more permanent results would be obtainable, too, if he could find some way to safely reduce the patient’s body-core temperature below 88 degrees Fahrenheit, but the means to do so have thus far eluded him. Still, even such limited progress as Mason has made causes a big enough stir when he gives a preliminary presentation of his findings for the media. That’s actually something of a problem, though, because the press (being the press) is now talking up Mason’s promising experimental treatment as a currently available cure. Mason’s boss, Dr. Harvey (Charles Trowbridge, from Valley of the Zombies and Mad Love), steps in to turn down the volume on the publicity, which among other things entails sending Mason away on vacation and shifting responsibility for all future frozen therapy work to an impersonal panel of less photogenic doctors. Mason is a little annoyed, but he understands and indeed agrees with Harvey’s reasoning.

Tim Mason is no appreciator of idleness, however, and a little nudging from his fiancee, nurse Judith Blair (Jo Ann Sayers), cements his resolve to make this a most ambitious working holiday. All along, Mason’s frozen therapy studies have been guided by the research diaries of Dr. Leon Kravaal, which hint at marvelous successes in the field, but remain frustratingly vague as to how they were achieved. Kravaal disappeared under mysterious circumstances a decade ago, too, so it isn’t as though Mason can call him up and ask for pointers. His last known whereabouts were a house on an island in the middle of Silver Lake, just below New York’s Canadian border, and Judith proposes that she and her boyfriend should spend their weeks of exile from the hospital on the hunt for anything Kravaal might have left behind up there.

The Man with Nine Lives makes its closest approach to being a standard 1940’s horror movie when Tim and Judith go to rent a boat for their reconnaissance on Crater Island, for the local coot who does the renting (ubiquitous bit-part guy Ernie Adams, whose more conspicuous castings include parts in The Invisible Ghost and The Return of the Ape Man) warns them away from the Kravaal house as insistently as if it were Castle Dracula. He’s inevitably none too forthcoming at first as to why, but Mason does eventually pry the story out of him. Evidently Kravaal was not the only one who disappeared from Crater Island ten years ago. With him when he vanished were three prickly out-of-towners named Hawthorne, Bassett, and Adams, together with Ed Stanton, the local sheriff. The waterman himself was among the posse that searched Crater Island for the missing men, and he can personally attest that there was no more sign of them than if they’d been abducted by aliens (or by whatever otherworldly agency was thought to abduct people in 1940). Naturally that tale holds little deterrent value for Judith and none at all for Tim, and the two travelers do indeed set off at once for the missing doctor’s abandoned house.

Their investigations turn up nothing of particular interest until Judith falls through a dry-rotted section of floor into a cellar that lacks any visible means of entering it normally. (We’ll later learn that access is through a secret door behind the grandfather clock in the parlor.) Secret cellars are curious enough all by themselves, but secret cellars communicating with mineshaft-like tunnels into the surrounding earth can’t help but stimulate even the dullest person’s sense of either foreboding or adventure. Tim and Judith answer to the latter, and they keep right on answering to it when the tunnel terminates in a staircase leading more than a hundred feet deeper underground. Descending those stairs brings the explorers to a sophisticated chemical laboratory and a crude surgical theater, occupied solely by a single human skeleton in a posture suggesting that its owner fell to his death while making the vertiginous climb to up to the tunnel. Could that be all that remains of Leon Kravaal? If so, then what about the other four missing men? Mason is pondering those questions when he notices the stout metal door at the back of the surgery— the one covered over completely with a thick layer of frost. The doctor is not a stupid man, and it would take a very stupid one indeed not to suspect a link between that frost-encrusted door and the topic of Kravaal’s research. Sure enough, when Mason hacks his way into the icebound chamber behind the door (oh, hey— there’s the British title), he finds a frozen body in a seemingly perfect state of preservation inside.

Reasonably assuming that they’re looking at a case of frozen therapy gone overboard, Tim and Judith immediately set about thawing out the man from the ice room according to their usual protocol. When their efforts succeed a few hours later, they learn that their patient is none other than Dr. Leon Kravaal himself (Boris Karloff). Kravaal naturally didn’t intend to freeze himself— and he sure as hell didn’t mean to freeze himself for ten years without telling a soul on Earth what he was up to. It’s rather a long story how the doctor’s predicament came about, and it begins with Jasper Adams, that skeleton his rescuers found earlier.

Adams was suffering from a deadly disease, and mainstream medical opinion held that his was a hopeless case. He came to Kravaal in 1930, having heard about the doctor’s experiments with frozen therapy, and Kravaal thought Adams was a good candidate for treatment. Unfortunately, Adams had a nephew— a grasping young man named Bob (Before I Hang’s Stanley Brown)— who, as Jasper’s sole heir, took a strong interest in his uncle’s health. When Bob learned that Jasper had signed himself up for some kind of experimental therapy, he immediately started pestering Dr. Kravaal, demanding to see his uncle, and to know exactly what this treatment regimen consisted of. When Kravaal told the younger Adams that was none of his business, the latter man went to the authorities, and the next thing Kravaal knew, he was in the office of District Attorney Hawthorne (John Dilson, of The Leopard Man and Man-Made Monster) being threatened with prosecution for murder— Bob Adams having just about convinced the DA that the reason Kravaal wouldn’t let anyone see Jasper was because the experimental therapy had killed him. The real reason, of course, was that Jasper Adams was reposing in that subterranean ice chamber, while Kravaal knew perfectly well that men like Hawthorne and Dr. Henry Bassett (Byron Foulger, from The Rocket Man and The Black Raven), the physician Adams hired to debunk Kravaal’s claims, would not see any difference between a controlled cryogenic coma and freezing to death. Nor indeed did they when Kravaal finally bowed before Hawthorne’s threats and took him, Bassett, Adams, and Sheriff Stanton (Hal Taliaferro) to see his laboratory on Crater Island. Bassett rushed the patient out of the cold room, Stanton tried to place Kravaal under arrest, and the doctor’s efforts to regain control of the situation resulted in everybody save the unfortunate Jasper Adams being accidentally put into suspended animation. Mason does indeed find the still-frozen interlopers when Kravaal tells him where to look, but thawing them out does nobody any good. Adams, Hawthorne, Bassett, and Stanton go right back about the business they were on before they got frozen, and some of Adams’s antics cause the destruction of a crucial piece of Kravaal’s notes. That’s when the good doctor finally loses it. Understanding the implications of those ten years frozen in the cellar much more clearly than his antagonists, Kravaal determines to recreate the experiments whose records Adams destroyed, using the officially dead men currently sequestered in his basement as his lab rats— and if Tim and Judith know what’s good for them, they won’t try to stand in his way!

It really is almost exactly the same story as The Man They Could Not Hang all over again, but The Man with Nine Lives presents it with substantially more panache. To start with the littlest thing, I love how cheesy and slapdash Dr. Mason’s demonstration for the press is. It looks exactly like the footage of Robert E. Cornish’s dog-reviving experiment that served as the nucleus of Life Returns six years earlier. Karl Brown makes a lot more of the tie between the mad doctor and the protagonist couple than he did the last time around, considerably increasing the tension in the film. Tim and Judith may have blundered into their roles in Kravaal’s increasingly evil scheme just as circumstantially as Scoop Foley and Janet Savaard, but The Man with Nine Lives benefits from all the complications that arise out of Mason’s status as the protégé Kravaal never knew he had, to say nothing of the moral compromises that he and Judith get themselves into simply by following their instincts as medical professionals. Leon Kravaal is a more sharply delineated character than Henryk Savaard, too, improving the credibility of the villain’s descent into madness. The specific terms on which Kravaal finally snaps feel organically connected to what we’ve already seen of his “normal” personality, in a way that simply was not the case with Dr. Savaard in Columbia’s initial mad doctor flick. It’s also worth pointing out this movie’s almost complete abandonment of the spooky house model to which The Man They Could Not Hang clung so counterproductively once Savaard’s revenge plot got fully underway. The Man with Nine Lives feels much more like its own thing without all those 1920’s leftovers cluttering up the final act, even despite being a barely disguised reworking of a film made only a few months before. Finally, The Man with Nine Lives ends on a pleasingly disturbing note, attempting to come to grips with the ethical issues raised by its premise in a way that its predecessor never did. Remember that Kravaal’s frozen therapy technique, like Savaard’s resuscitation machine, works just as it was designed to, and has enormous value for the advancement of medical science. Remember also that unlike Savaard, Kravaal puts the finishing touches on his work by experimenting on several most unwilling human subjects. Most importantly, because the heroes of this film are themselves medical professionals, and are in fact engaged in the very same area of research, Kravaal cannot realistically take the secrets of his ill-gained triumph to the grave (which is the usual way for old horror and sci-fi movies to get around this problem) unless the filmmakers are willing to kill off the protagonists, too. That would obviously have been out of the question in 1940, so Brown must eventually face up to the issue of how Dr. Harvey back at Mason’s hospital and the industry he represents will react to a groundbreaking therapeutic technique that rests on a foundation of multiple murder. Let it suffice to say that Brown’s resolution of that issue strikes me as utterly and uncomfortably realistic, both in substance and in tone.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact