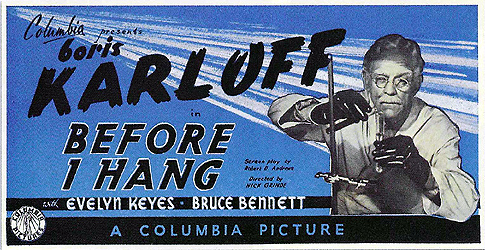

Before I Hang (1940) **½

Before I Hang (1940) **½

Everywhere I look, the consensus on Before I Hang seems to be that this is the lame entry in Columbia’s mad doctor cycle, the point at which the premise reached the creative equivalent of nutrient exhaustion. As usual, I’m not at all sure I agree. True, Before I Hang is in most respects a noticeable step down from The Man with Nine Lives, but it isn’t really any worse overall than The Man They Could Not Hang, and it reflects a clear effort on its creators’ parts to keep the series from repeating itself too blatantly while still remaining within the same thematic territory. It’s also by far the best-looking entry to date— and indeed the studio’s best-looking horror film, period, since The Black Room— with lots of imaginative lighting design and tricky cinematography giving it an infusion of visual interest to make up for whatever it lacks in freshness of subject matter.

This time, we begin with the mad doctor already in the dock and on trial for his life, even though he has not yet gone mad. Dr. John Garth (Boris Karloff) is a gerontologist who has become convinced that the ravages of age are all avoidable, reversible phenomena. After all, if all the tissues in the body of each living multicellular organism are ultimately traceable to a single zygote (which they are), and if each zygote is formed from gametes which are themselves created by the division of cells within the parent organisms’ bodies (which is also true), then cells per se are effectively immortal; this is even more obvious in the case of unicellular lifeforms, where reproduction occurs by the simple expedient of the individual dividing into two new one-celled creatures. There must be some special side-effect of multicelluarity that inhibits over time the natural, open-ended growth and replacement of cells, leading eventually to the breakdown of our bodies and the termination of our lives, and if that side-effect could be identified, isolated, and counteracted, then it should become possible to eliminate old age in and of itself as a potential cause of human death. Garth believes that the culprit in the aging process is the accumulation of certain toxins within the body, which the means of elimination we inherited from our most distant single-celled ancestors are inadequate to cope with due to the dense packing of our millions of cells. He has spent the past several years hard at work to develop a serum that will break down those toxins into harmless compounds, and his reputation is such that he eventually attracted a wealthy and very desperate patient who was in the most advanced stages of enfeeblement and decrepitude, but whose heart and brain remained strong enough thanks to a vigorous youth that he was unable to die. This man became Garth’s guinea pig for a multitude of serum formulations, but nothing seemed to do the trick. Eventually, despair got the better of him, and he begged Garth for an injection that would painlessly end his increasingly miserable life. It is that act of hubristic mercy that now has Garth before a court of law, which eventually finds him guilty of premeditated murder and sentences him to hang within a month’s time. And despite the best efforts of Garth’s daughter, Martha (Evelyn Keyes, from A Thousand and One Nights and A Return to Salem’s Lot), and colleague, Dr. Paul Ames (Bruce Bennett, of The Alligator People and The Shadow of Chinatown), the state supreme court finds no grounds for hearing an appeal of the case, and the governor refuses to grant clemency.

A funny thing happens to Garth in prison, though. A week after his incarceration, the warden (Ben Taggart, from Man-Made Monster and the 1917 version of She) calls him into the office for a meeting with Dr. Howard (Edward Van Sloan, from The Mask of Diijon and The Face Behind the Mask), the staff physician. Howard is familiar with Garth’s work, and while he certainly doesn’t condone euthanasia, he nevertheless recognizes the prisoner’s anti-aging research as perhaps the most important line of medical investigation going on in the world today. With the warden’s permission, Howard offers Garth the use of the prison infirmary so that he may spend his last three weeks on Earth productively, and perhaps grant the world one last parting gift of his genius. Garth, dedicated to the last, agrees at once, and soon he and Howard are assembling a lab in the back of the infirmary, stocked with everything Garth will need to carry on his serum studies.

The big breakthrough comes maybe a week before Garth’s date with the gallows. As soon as he has a serum that seems to perform according to spec, Garth persuades Howard to use him for the first experiment on a human subject. Howard will inoculate Garth on the day of his execution, monitor his vital signs until zero hour, and then perform a meticulously detailed autopsy with the aim of discovering every little thing that the anti-aging drug did to his cells. It’s a lucky break for Garth that he was sentenced to death by hanging, for electrocution, cyanide gas, and lethal injection would all produce system-wide derangements sufficient to render any such undertaking mostly pointless. There’s one last hurdle to overcome, in that Garth’s experiments so far have almost completely exhausted the infirmary’s supply of the human plasma necessary for making his serum, but there are other men on death row, and it’s only a minor hassle for Howard to draw off large amounts of plasma from the next man to go to his death before the condemned doctor. A sizeable monkey wrench gets thrown into the machinery of Garth’s final experiment, however, when the governor has last-minute second thoughts, and commutes his sentence to life imprisonment literally moments before the scheduled hanging. Howard is thus prevented from autopsying Garth, but the chance to make close observations on the responses of a live patient to the serum is in some ways even more valuable. The treatment subjects Garth to a dangerous degree of system shock, but its performance is impressive indeed. When Garth regains consciousness a few days later, he has the body of a man some twenty years younger than his true age.

Screenwriter Robert Andrews makes an interesting feint at this point in the direction of unintended consequences, with Garth seeming to realize the significance of a life sentence that just got a likely minimum of twenty years longer, but that, somewhat disappointingly, is not where Before I Hang is headed. It soon becomes apparent that Garth is actually okay with having all the time in the world and no demands on how to fill it save the dictates of his own studies. The trouble, rather, is the source of that serum Howard injected into him. Its plasma base, you will recall, came from the body of a second death-row inmate, extracted immediately after his execution. And death-row inmates, you will recall, don’t typically earn their places by rescuing kittens from treetops or helping little old ladies across the street. That’s right— Before I Hang is about to become The Blood of Orlac, except that Howard really did shoot Garth up with a killer’s instincts along with the killer’s plasma. Things only get worse, too, when word of Garth’s triumph gets out, and the governor yields to public pressure in favor of a “hero’s pardon” for the imprisoned doctor.

Actually, that hero’s pardon business is the biggest single flaw in Before I Hang’s story logic. Published reports of Garth’s successful experiment are the only way to make sense of a widespread outcry for his release, but the whole rest of the movie hinges on the supposition that his mastering of the aging process is as yet known to nobody but Howard and the warden. Even his closest associates— Ames, Martha, the three stuffy old duffers whom he attempts to enlist in an effort to replicate the experiment that de-aged him— all assume that his restoration to comparative youth stems from some kind of mysterious biological fluke, and it isn’t until Detective Captain McGraw (Don Beddoe, from Jack the Giant Killer and The Wizard of Baghdad) starts following Garth’s trail of bodies that anybody outside the prison begins to wonder if maybe Garth got up to something unusual while he was behind bars. I always wonder, when I see plotting fuck-ups like that in a rapidly produced B-movie such as this one, if maybe the rigors of a compressed production schedule are to blame. Like maybe Robert Andrews didn’t think of the secrecy angle until rewrite time, but the quick turnaround demanded by the producers left him in too big a hurry to make sure he’d excised all traces of a previous third-act draft in which the outcome of the prison experiment was well publicized, you know? Whatever the cause, it casts a nagging shadow of “Yeah, but…” over the whole second half of the film, which is otherwise a fairly accomplished update of the old Hands of Orlac premise. Karloff, predictably, makes a terrific go of playing a man who murders repeatedly against his will, becoming more horrified by his own behavior which each life he takes. Evelyn Keyes enlivens the basically thankless part of a typical do-nothing 40’s heroine with a hint of the winsome charisma that would come close to saving A Thousand and One Nights five years later. And of course, Before I Hang does something that neither of the preceding legitimate Orlac movies did, dispensing with the annoying bullshit frame-up conclusion. This movie makes a bona fide serial killer out of a fundamentally good (if perhaps ethically compromised) man, and it never once flinches from the implications of doing so.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact