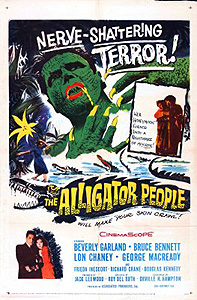

The Alligator People (1959) -**½

The Alligator People (1959) -**½

Most of the time, when we think about perfect casting, we mean the alchemy that occurs when an actor is so good and so right for the part that it becomes next to impossible to imagine anyone else doing it. Examples from my experience would include Vincent Price as Matthew Hopkins in The Conqueror Worm, Boris Karloff as the grave robber John Gray in The Body Snatcher, and John Huston as the voice of Gandalf in the Rankin-Bass Tolkien cartoons from the 70’s. But there’s another species of perfect casting, one which is perhaps even rarer, and which doesn’t attract nearly as much attention. Sometimes you’ll find an actor in a role that practically seems to have been written for him as a joke at his expense. Consider The Alligator People, in which Lon Chaney Jr., who by that point in his career was a big, useless drunk who was often barely tolerated by his employers, finds himself cast as a big, useless drunk who is barely tolerated by his employers!

There’s a framing story involving a nurse who reveals an alternate personality under hypnosis, but I’m going to ignore all that— partly because I hate writing movie reviews in the past tense and partly because most framing stories (and this is no exception) are just lame. The real movie is about a woman named Joyce Webster (Beverly Garland, from It Conquered the World and Curucu, Beast of the Amazon), who has just gotten married to former army fighter pilot Paul Webster (Rocky Jones, Space Ranger himself, Richard Crane). The two of them are on the train to their honeymoon, and though no one was supposed to know their transportation arrangements, they are nevertheless besieged by telegrams of congratulation from their friends. One of those telegrams is not like the others, however. It’s for Paul, and whatever it says is obviously very worrisome— so worrisome, in fact, that he gets off the train when it makes a 30-second stop to pick up mail, and leaves his new wife calling desperately to him from the window of their compartment.

Joyce spends most of a year looking for Paul, realizing while she’s at it that she knows almost nothing of his background. Eventually, she remembers the name of the college he attended, and is somehow able to convince the school administration to release Paul’s records to her. That gets her the address that he claimed as his childhood home, a defunct plantation called the Cypresses, deep in the Louisiana bayou. As it turns out, the Cypresses isn’t the only thing in the neighborhood that’s defunct— there’s scarcely anything left of the nearest town, and the train station where Joyce gets off is practically deserted. No one else left the train with her, and her only company on the platform as she tries to figure out what to do next is a large wooden crate with “Cobalt-60, Danger— radioactive” stenciled on it.

That crate gives Joyce an idea. She figures nobody is going to let a bunch of cobalt-60 lie around unclaimed for very long, and that someone will surely be along to fetch it shortly. When that happens, she’ll just ask whoever it is if she can get a ride to the Cypresses. Well interestingly enough, the man who comes for the cobalt is from the Cypresses. His name is Manon (Chaney), and I guess he’s supposed to be a Cajun— Chaney could never fake an accent even when he was sober, and he doesn’t even try here. On the way to the plantation, it comes out in conversation that Manon has an intense hatred of alligators, one of which bit off his left hand many years ago and left him to get by with a patently phony hook. You think this might be important in a movie called The Alligator People?

Joyce’s reception at the Cypresses is, shall we say, disappointing. The mistress of the house, Lavinia Hawthorne (Frieda Inescort, from The Return of the Vampire and The She-Creature), is not at all happy to see her, and the only reason Joyce isn’t immediately booted out on her ass is that there won’t be another train coming along to take her out of town until the next day. Despite what the college has to say on the subject, Lavinia claims never to have heard of anyone by the name of Paul Webster, and as she’s lived on the old plantation for decades and decades at a stretch, it doesn’t seem likely that any such man had been living there when Paul gave his address to the admissions office. But Lavinia’s disavowal is so strident that it can’t possibly be anything other than a big, fat lie, and Joyce, smart girl that she is, assesses the situation instantly. Moreover, what imaginable reason would Lavinia have for insisting that Joyce not leave her room during the night, or for locking her in so as to make sure that her orders are complied with unless she were hiding something? Well, perhaps that something is the man whom Joyce finds playing the piano in the darkened parlor when she escapes from her bedroom— the soggy, muddy, scaly man who just happens to look a whole hell of a lot like Paul Webster.

As Joyce will gradually learn over the next couple of days (she makes a big pest of herself and refuses to leave the Cypresses in the morning), it’s like this: Paul Webster, as Joyce already knew, had been shot down once during the war, and though you wouldn’t have guessed it from looking at him, he suffered extensive injuries that nearly killed him. The doctor who saved Paul’s life, a surgeon/medical researcher named Mark Sinclair (George MacReady, from Soul of a Monster and The Human Duplicators), was able to do the job only by subjecting his patient to an experimental treatment. Impressed by the healing properties of the hormone hydrocortisone, Sinclair began extracting the stuff from reptiles— alligators in particular. This is because (or so screenwriter O. H. Hampton would have us believe) reptiles are so much more dependent upon their endocrine systems than we are, and thus secrete far more potent versions of their hormones. Sinclair began shooting up his most seriously injured patients— Paul among them— with alligator hydrocortisone, and achieved nearly miraculous results. But because this sort of thing always happens in movies from the 50’s, those hormone treatments had the unexpected side effect of gradually gatorizing the men who received them. That’s what that alarming telegram Paul got on the train was about; Sinclair wanted him to come back and get help before the changes started. Paul really did live at the Cypresses (in fact, Lavinia is his mother), and Dr. Sinclair, helpfully enough, lives right down the road. That cobalt Manon picked up from the train station was intended for the doctor’s lab, as Sinclair has determined that radiation seems to have a controlling effect on his patients’ transformation. As for all the secrecy, the whole thing was Paul’s idea. He didn’t want his wife to know that he was turning into a monster, and wanted to stay out of her sight unless and until Sinclair found a cure for him. And as you’ve probably figured out, the monkey wrench that will inevitably find its way into Sinclair’s well-wrought plans to correct his gigantic screw-up is named Manon. That cranky old lush doesn’t like the two-legged ‘gators Sinclair has hanging around in his lab any more than he likes the four-legged ones who live in the surrounding swamp.

The Alligator People is a charmingly stupid film, but ultimately no more than that. Its main selling points are an uncommonly embarrassing performance from Lon Chaney Jr. and the exceptionally loopy monster suit representing the final phase of Paul’s transformation, which was designed by the man who did the same job on The Fly and its first sequel. (In fact, The Alligator People was originally released on a double bill with Return of the Fly.) Otherwise, there really isn’t anything here that you haven’t already seen in half a hundred earlier 50’s monster cheapies. The ‘gator-man sure is a hoot, though (somehow the fact that he’s wearing pants makes him about six times as funny as he would have been naked), and Chaney’s distractingly complete failure to disguise the presence of his perfectly functional left hand underneath that sorry-ass hook (which his dialogue requires him to call attention to every single time he appears on camera) is another big chuckle-generator. Nothing to write home about, but you’ve sat through worse.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact