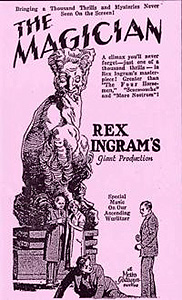

The Magician (1926) ***

The Magician (1926) ***

The mass talent migration from the German movie industry to Hollywood during the later 1920’s and early 1930’s is a much-discussed phenomenon, and as I’ve mentioned elsewhere myself, it was one of especial importance for the development of the American horror film. With Conrad Veidt taking on Gwynplaine in Universal’s The Man Who Laughs, Peter Lorre reinterpreting one of Veidt’s old roles in Mad Love, former Golem crewmembers blossoming into important second-tier directors in the United States, and so on, it’s hard to turn over a rock in an old American fright flick without finding a German toiling beneath it. There’s at least one case, though, of a noteworthy Teutonic screen bogeyman working under American auspices not because he came to Hollywood, but because Hollywood came to him.

There had been no movie industry to speak of in Southern California until 1911, when independent-minded filmmakers fed up with the Motion Picture Patents Company began flocking from New York and Jacksonville to Los Angeles, precisely because it was as far away from Thomas Edison as they could get without leaving the country. Hollywood did not remain a creator’s paradise for long, however, and already by the 1920’s, the West Coast studios were coming increasingly to be dominated by men who cared more about making money than they did about making art. In as capital-intensive a medium as film, it could hardly have been any other way. One of the those ascendant moneymen was Louis B. Mayer— the second “M” in MGM— and one of the artistic purists on Mayer’s payroll with whom he frequently clashed was an Irish transplant named Rex Ingram. In 1926, Ingram finally grew sufficiently weary of what he considered Mayer’s meddling to make a second escape of his own, only he actually did flee the country. Relocating to France, he set up shop in Nice, where he turned the then-disused Victorine studio complex into what amounted to a colonial outpost of MGM. (Some indication of Ingram’s loathing for Mayer can be gleaned from the fact that the films he shot overseas invariably carried the legend “A Metro-Goldwyn Picture” in their main titles. We might also take the fact that the snub was always allowed to stand as an indication that Mayer didn’t give a shit what his underlings thought of him, provided they turned out profitable work.) The second of Ingram’s productions in self-imposed exile was The Magician, adapted from W. Somerset Maugham’s fictional hatchet-job on Aleister Crowley, and it was only natural that Ingram would want some German horror luminary in the Crowley role. Assistant director Michael Powell (who would later fuck up a long and successful career by making the phenomenal Peeping Tom) would have preferred Conrad Veidt, but Ingram had recently screened The Golem, and he gave the part to Paul Wegener instead.

Somewhere in the Latin Quarter of Paris (so called because of the language traditionally spoken in the lecture halls of its numerous colleges and universities) stands the studio where sculptress Margaret Dauncey (Alice Terry) does her work. One afternoon, the massive statue of a seated satyr to which she has been devoting most of her recent efforts collapses under its own titanic weight, leaving Margaret pinned beneath several hundred pounds of unfired clay. Margaret’s roommate, Susie Boud (Gladys Hamer), is quick in summoning help, but the damage is already done. The girl’s spine was seriously injured in the accident, she now has no feeling in her legs or lower body, and the doctor who initially examines her sees little hope of her ever recovering. Luckily for Margaret, however, her guardian uncle, Dr. Porhoët (Firmin Gémier), is a well-connected physician himself, and the teaching hospital where he works is currently hosting an extremely talented American surgeon by the name of Arthur Burdon (Ivan Petrovich, from the 1928 version of Alraune). Burdon believes he can indeed repair Margaret’s spine, and he agrees to undertake the necessary operation at once.

Given that this is a teaching hospital, it’s only to be expected that it would draw a big crowd when the visiting star surgeon performs an operation that pushes the limits of medical science. Among those assembled med students is one Oliver Haddo (Wegener, from The Student of Prague and the silent German Svengali), a strangely intense man whose advanced age as compared to his classmates may be intended to imply that he developed an interest in surgery only after a long time spent pursuing some other career. (Silent movies were rarely cast with much thought given to whether an actor was the right age for his or her part, though, so the twenty years or so that separate Haddo from his fellows could simply be a happy accident.) Certainly Haddo is already notorious for things other than his medical learning— he’s an occultist and hypnotist who claims mastery of legitimate magical techniques, and there is every reason to believe that his studies at the hospital relate more to advancing his professed wizardry than to any desire to heal the sick. Witness, for example, his dismissive reply to one student’s marveling over Burdon’s “magical” skill with his scalpel: “Saving a life is no great accomplishment. Creating life— that requires real magic!”

Yes, that means exactly what you think it does, and the next time we see Haddo, he’s in the university library, poring over rare and ancient texts in search of a forgotten formula for creating and animating a homunculus. Ingram remains decorously silent on the details when the sorcerer finds what he’s looking for, but the key ingredient is, inevitably, the heartblood of a blonde, fair-skinned maiden with blue or gray eyes. And now that you mention it, that description does seem to fit Margaret Dauncey rather well. Haddo’s subsequent efforts to ingratiate himself to the girl after her recovery are somewhat impeded by the romance developing between her and Arthur Burdon, but we’ve already established that hypnosis is one of the magician’s many talents. As usual, hypnosis in a horror movie means something rather different from what it generally means in real life— when Haddo drops in to lay his whammy on Margaret, the result is something resembling a tamer revamp of the black mass scene from Witchcraft Through the Ages, with Haddo inducing in his prey a vision of satyrs and nymphs frolicking wantonly in a stony grotto tinted an infernal red. From that moment on, Margaret has less and less control over her own actions, until she finally winds up marrying the magician against her will. Burdon and Porhoët know at once that something untoward must be going on when that news gets out, and they proceed to hound Haddo all over Europe in a quest to free Margaret from what they rightly assume is his domination. What they don’t realize, of course, is that Haddo isn’t at all interested in Margaret as a woman. The marriage was nothing more than a stratagem to preserve her virginity until the day when he’s ready to retreat to his secret laboratory in the loft of a remote medieval keep, where the raw materials for his homunculus are being gradually amassed.

Wait a minute— secret monster-making laboratory? Medieval keep? Why yes, I do believe that is the second act of Frankenstein taking shape five years early. Hell, Haddo even has a diminutive hunchbacked flunky (Henry Wilson, who also played villainous henchmen in the Eille Norwood Sherlock Holmes movies The Sign of Four and The Speckled Band) much like Dwight Frye’s Fritz. Meanwhile, the seduction, capture, and pursuit of Margaret which consumes much of The Magician’s second half bears more than a passing resemblance to the 1931 version of Svengali, and the set design for Haddo’s lab makes it a dead ringer for Dracula’s Carfax Abbey. I would very much like to know how much of this foreshadowing of major first-generation horror talkies is coincidence and how much is actual influence; The Magician may be little remembered today, but it was a fairly recent film when Tod Browning, James Whale, Archie Mayo, and their collaborators were making their contributions toward defining Hollywood horror, and with MGM’s muscle behind The Magician’s marketing and distribution, you’d expect it to have been pretty widely seen. At the very least, the similarities are hugely suggestive. At most, The Magician may have a great deal to tell us about how modern perceptions of trends in movie history are distorted by the vagaries of access and preservation. What obvious links to the deeper past could we be missing in seemingly groundbreaking early films, simply because inspirational antecedents have gotten lost or faded into obscurity?

As I’ve already implied, Michael Powell was not impressed with Paul Wegener, describing him as “a pompous German whose one idea was to pose like a statue and whose one expression to indicate magical powers was to open his huge eyes even wider, until he looked about as frightening as a bullfrog.” I can’t really argue with that assessment of Wegener’s performance in The Magician, but Powell missed a very important point in making it. Yes, Wegener is a pompous ham here, acting in a style that was already hopelessly obsolete in 1926, however appropriate it might have seemed in the days of Monster of Fate and The Student of Prague. However, Oliver Haddo is a ham himself, and is to all appearances even more pompous than the man portraying him. That being so, Wegener’s playing to the cheap seats is just what the role demands, and the impossibility of taking Haddo seriously as a threat until after Margaret is safely in his clutches becomes a point in The Magician’s favor. Audience and characters alike write Haddo off as no more than an irritating buffoon, and it comes as an effective shock when we see how far we’ve underestimated him. This is another way in which The Magician prefigures the 1931 Svengali, although Wegener does not convey, to my eye, an impression of the villain strategically encouraging such underestimation like John Barrymore would in the later film. Rather, I imagine Haddo seething inside about how he’s going to show everyone whom they’re really dealing with one of these days, and fantasizing about the looks he’s going to see on their faces when that day finally comes.

With that in mind, I find it doubly interesting that The Magician stops short of revealing just how real Haddo’s professed skill in the black arts is. Clearly he’s an organic chemist of considerable ability, and he’s certainly got hypnosis (possibly including self-hypnosis, depending on how you wish to read one scene involving a poisonous snake) nailed down. But would his homunculus really have come to life if he’d managed to bleed Margaret like he planned? (Look— it’s an MGM movie from 1926; I refuse to consider it a spoiler to mention that the good guys win.) We don’t know. In fact, we can’t even be sure that Haddo ever had a homunculus in the first place— there’s no counterpart in Haddo’s lab to Boris Karloff under the sheet, awaiting the lightning strike that will trigger Frankenstein’s cosmic ray projector. Realistically speaking, this is probably no more than the usual Hollywood squeamishness about the supernatural, the phenomenon that would insistently turn ghosts into gangsters and vampires into disguised detectives for another four years or so. But even if leaving an opening for a rational explanation was the only actual aim, the way Ingram handled it turns what could have been (and typically is) an obnoxious cop-out into an honest and deliberate-looking ambiguity. The Magician thus feels decades ahead of its time, steering a middle course between avowing the supernatural and denying it in an era when the avowal alone would have been radical enough.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact