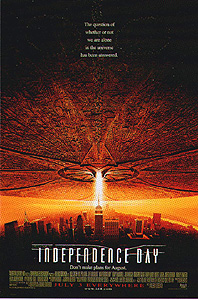

Independence Day (1996) **

Independence Day (1996) **

Who doesn’t love to see aliens blasting the shit out of world-famous landmarks? And who doesn’t think improbably enormous UFOs are cool? Right you are— fucking nobody, that’s who! So how can it be that Independence Day is so poorly regarded today despite the barrels of money it made in the theaters twelve years ago, despite the unprecedented lavishness of its landmark-annihilation scenes, and despite the almost unequalled improbable enormity of its UFOs? Well, for starters, it was directed by Roland Emmerich, produced by Dean Devlin, and written by both of those clowns working in tandem. Independence Day isn’t quite the turd-burger that the same team’s later Godzilla remake was, but it shares all of the same fundamental defects. It is an overlong and completely empty exercise in mindless spectacle that paradoxically spends but a fraction of its running time on the elaborate action that is its only reason for existing, and it represents another thoroughly wrong-headed attempt to apply the old Irwin Allen disaster-movie formula to a genre that requires a completely different approach.

July 2nd, some year in the early 21st century (which is to say, far enough in what was then the future that Bill Clinton would no longer be in the White House, but near enough that someone who had commanded a fighter squadron in the first Persian Gulf War would still be just barely old enough to satisfy the constitutional age requirement for the presidency). Radio telescope operators at the New Mexico headquarters of the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence pick up the signal for which they’ve been scanning the sky for years. The funny thing is that the alien transmissions are coming from the vicinity of the Moon. Further investigation reveals an object just inside Lunar orbit, moving steadily in Earth’s direction. This is troubling because the object in question is roughly one fourth the Moon’s size, and a collision between it and the Earth would be instantly fatal for everything on this planet. The good news is, it’s slowing down; the weird news is, asteroids don’t do that, so it seems there’s nothing else for it to be but an extraterrestrial spacecraft. The SETI scientists call the US military’s Space Command, and General William Grey (Robert Loggia, of The Ninth Configuration and Psycho II) in turn calls President Thomas Whitmore (Bill Pullman, from Lake Placid and The Serpent and the Rainbow). Obviously, this is rather a big deal for the president. For one thing, visitors from space promise to pose the stiffest challenge yet to his leadership, which has been embattled enough as it is simply because of his youth and inexperience with the practicalities of Washington politics. Then again, here, at last, is a situation to which his military background might be relevant— he may be weak and ineffectual when it comes to setting policy, but if there’s one thing Thomas Whitmore knows how to do, it’s taking calm and decisive action in an emergency. And since the one fact about the aliens that can be gleaned from their behavior in orbit is that they don’t like our spy satellites very much, it’s a more than reasonable possibility that a crisis is indeed in the offing. Nor does the aliens’ deployment of 30-some city-sized flying saucers to take up positions over the world’s major capitals and industrial centers— including Washington, New York, and Los Angeles— offer any obvious basis for putting aside such worries.

In point of fact, the president and his advisors haven’t guessed the half of it yet. Up in New York, telecommunications scientist David Levinson (Jeff Goldblum, from Jurassic Park and The Fly) is trying to figure out why satellite communications all over the globe have been buggy since early that morning, and he’s just discovered that all of the satellites’ transmissions are carrying an embedded signal. It comes in pulses at regular intervals, building to an incrementally smaller amplitude each time, and according to Levinson’s calculations, it ought therefore to fade away to nothing in about six hours. Levinson is very much the kind of guy who lives mostly in his own head, and he had been so busy pinning down the satellite distortion that he never even heard about the arrival of the aliens. He hears about it now, though, and it suddenly occurs to him what the strange, distorting signal he’s been chasing is— it’s a countdown. If the mothership is broadcasting a countdown to the saucers over the cities, then that must mean the aliens have some big operation planned that requires precise coordination. And if they’re hiding that countdown in our own television and radio broadcasts, that must mean they don’t want us to know about it. No, that can’t be good. By a fortuitous coincidence, Levinson’s ex-wife, Constance Spano (Margaret Colin), is the White House press secretary, so Levinson has at least some tiny chance of conveying his ominous discovery to somebody who is in a position to do something about it. Constance refuses to talk to him, though, so Levinson drops in on his father, Julius (Judd Hirsch)— who, unlike David, owns a car— and talks him into driving him down to Washington to deliver the message in person.

Matters are complicated by the fact that, back when the president was just a jet-jockey and Constance was just a friend of his, Levinson once started a fight with Whitmore, because he thought the two of them were having an affair. Whitmore, in other words, will not be much happier to see Spano’s ex-husband come barging into the White House than she will. But the President of the United States can’t afford not to take people seriously when they tell him, “Hey, you know what? We’re all about to die!” so the message does eventually reach its intended destination. The trouble is, there’s only about half an hour left to the countdown by then, which is going to make evacuating DC, LA, and New York rather difficult. Whitmore and his staff (of which the Levinsons may be considered de facto members by this point) have a close enough call just getting Air Force One off the ground before the saucer hovering with its center above the White House deploys its gimongous death ray, and vaporizes the whole city. New York and Los Angeles go up in smoke at the same moment, raising the question of what became of Whitmore’s wife, Marilyn (Donnie Darko’s Mary McDonell), who had been in LA on some manner of business when the aliens arrived.

With the aliens’ intentions now unambiguously established, the military springs into action. At Del Toro air base, Marine Corps Captain Steve Hiller (Will Smith, from I Am Legend and Men in Black) leads his F/A-18 squadron— the Black Knights— in an attack on the saucer that destroyed LA. It does not go well. The alien vessel is protected by an impenetrable forcefield, and the Black Knights’ AIM-120 missiles detonate harmlessly about a hundred yards from the ship’s hull. (Mind you, those missiles weren’t going to do shit worth of good, anyway. Fragmentation warheads designed to tear the control surfaces off of airplanes are pretty much worthless for large-scale demolition work, and I really can’t see something as big as the alien attack ships being bothered by anything short of a BGM-109 cruise missile.) Then the saucer disgorges its own swarm of fighter aircraft (also forcefield-protected), which make short work of Hiller’s squadron. Hiller alone survives, and he is the only one to down an enemy fighter; the latter he does almost by accident, and without doing it more than superficial damage. Hiller is also the first human to see one of the aliens, when the pilot of the crashed fighter climbs out of its cockpit— and for that matter, he’s the first human to punch one of them in the face, too.

Meanwhile, the saucers are traveling from city to city, raining down destruction as they go. There’s some talk of unleashing the nation’s nuclear arsenal against them, but that plan is not very popular, and is in any event rendered impracticable by the incineration of SAC-NORAD headquarters. Recriminations begin flying throughout Air Force One, with nobody recriminating louder than Julius Levinson, who berates the assembled officials for getting caught with their pants down even though they’ve had an alien spaceship in cold storage at Area 51 for some 50 years. At first, everybody scoffs at the elder Levinson’s angle of attack, but then the secretary of defense shamefacedly admits that there is indeed an Area 51, and there is indeed an alien vessel in storage there. Whitmore, understandably peeved that nobody ever thought to tell him about that (I mean, he’s only the fucking president, right?), orders Air Force One to detour there immediately. Thus it is that we are introduced to Dr. Okun (Brent Spiner, in a futile attempt to get himself remembered as something other than Lieutenant Commander Data on “Star Trek: The Next Generation”) and his secret underground laboratory. Not only is there a partially functioning alien fighter there, Dr. Okun also has the preserved carcasses of the craft’s three crewmembers… you know— for all the good it did anybody. While Whitmore and the others process these revelations, Captain Hiller (together with the unconscious alien he’s been dragging along behind him in his parachute) has been picked up by a caravan of refugees led by the slightly cracked Russell Casse (Randy Quaid, of Parents and The Wraith), a crop-duster pilot who claims to have been abducted and experimented upon by aliens ten years ago. Because Hiller happened to spot Area 51 from the air while he was dogfighting with the invaders (he assumes it’s just an ordinary Air Force base), he has directed the refugees toward it, and while the guards at the front gate initially refuse to let even him onto the premises, the space monster he has wrapped up in his parachute proves to be a very persuasive alternative to a security clearance. Now Dr. Okun has a live alien to poke and prod (sadly, at no point does he ever order any of his assistants to ready the anal probe), but again this is not a very helpful development. The space creatures are telepaths, and they are able to use a sort of psychic scream to scramble the brains of any intelligent organism. The alien incapacitates Okun as soon as it regains consciousness, and attempts to do the same to President Whitmore before the soldiers accompanying him gun it down. All Team Earth gains from the close-quarters encounter is an awareness of the invaders’ aims— they travel the universe like driver ants, pillaging any inhabitable planet they can find and then moving on to the next when its resources are totally depleted.

That’s a serious enough threat to put the nuclear option back on the table, and General Grey manages to round up four B-2 stealth bombers in flying condition to launch an attack. The first into action, against the saucer that just blew up Houston, enjoys about as much success as an earlier flying-wing bomber had nuking aliens in War of the Worlds. That would seem to indicate Game Over, but David Levinson has an idea for something a little more subtle. He wants to write a computer virus to shut down the aliens’ shields, allowing whatever military forces can be scrounged up a chance to counterattack on slightly more even terms. That will mean getting aboard the mothership, but if Dr. Okun’s team (which is now Levinson’s team) can get the spaceship they’ve been sitting on since the 40’s up and running, that should be easier than it sounds. General Grey goes that plan one better, suggesting that the infiltration carry an H-bomb as well, to blow up the mothership from inside after the toxic software has been passed along to all the invasion ships in the terrestrial skies. Now it’s just a matter of finding somebody to fly that mini-saucer, together with enough pilots to constitute a credible strike force.

I’m sure there’s an object lesson in this for cheapskate PC users like myself— apparently if you have a Mac, you can hack into computers running on outer space operating systems that no human has ever had a chance to analyze. It’s an achievement of sorts, I guess, that that isn’t the dumbest thing about Independence Day, either. If this movie is to be believed, F/A-18 supersonic fighter-bombers handle enough like crop-dusting biplanes that what little retraining is necessary can be squeezed into an afternoon. Fireballs pouring through confined spaces can not only be outrun on foot (even in stripper heels), but are incapable of turning corners. Similarly, a Boeing 747 on takeoff accelerates faster than the shockwave and firestorm generated by a weapon powerful enough to incinerate a large city with a single shot. Space-alien technology develops at such a glacial pace that the exact same model of short-range fighter— and, more importantly, the exact same electronic IFF system— is still in service 50 Earth-years after the Roswell crash. An object with a mass of 18 quintillion metric tons can take up a geosynchronous orbit just a few thousand miles above the Earth without its gravity having any noticeable effect on the surface at all (and can perform a close-range fly-by of the Moon without doing more than to partially efface Neil Armstrong’s footprints in the dust). A single tactical nuclear weapon (something in the 20-kiloton range, judging by the size) is sufficient to obliterate an 18-quintillion-ton object, too. And so on, and so forth, for almost two and a half hours. Once upon a time, I’d have included Bill Pullman’s turn as the president in that litany of absurdities as well, but time, sadly, has shown Devlin and Emmerich to be better judges of national character than I. In 1996, I scoffed at the notion of a hapless nincompoop like Thomas Whitmore being elected president on the strength of his obviously irrelevant experience flying jet fighters in the Gulf War. Since then, however, the American people elected— twice— a nincompoop so hapless as to make Warren G. Harding look like Harry S. Truman, whose military record consisted of not showing up to fly jet fighters on the home front during Vietnam, and who couldn’t even manage a baseball team effectively. Pullman seems positively Solonic in comparison.

Nevertheless, as with Godzilla two years later, the cavalcade of cretinism proves less of a hindrance to Independence Day than Devlin and Emmerich’s determination not to make the movie the subject matter suggests. Independence Day is good for one thing— meticulous portrayals of destruction on an epic scale— and it does that one thing extremely well. Unfortunately, there’s very little of it in the movie, because the nad-handlers in charge are too busy getting their Irwin Allen on. When we could be watching the giant alien saucers etching a swath of ruin across the face of North America, we get stuck instead with Captain Hiller’s stripper girlfriend (Vivica A. Fox, of Idle Hands)— whom we don’t even get to see strip, by the way— camping out in the wreckage of LA with the badly wounded Marilyn Whitmore. Why settle for ass-kicking, city-leveling action, when there are blatherous attempts at heavy-handed irony to be had, am I right? Then there’s the reunion scene between Marilyn (actually dying by this point) and her family, which would almost be enough to earn Independence Day a slot in the Lifetime broadcast schedule, managing as it does to be even more maudlin than the similar scenes that invariably found their way into Allen’s 70’s disaster movies. Devlin and Emmerich have even copied Allen’s tendency to wedge washed-up second-string celebrities into any position where they can be made to fit. Thus we have Judd Hirsh hamming it up like he thinks he’s playing Jonathan Silverman’s dad in some God-awful Neil Simon schmaltz-fest, and worse yet, Harvey Fierstein in a completely pointless and boundlessly irritating part as one of David Levinson’s coworkers. Think back to Slim Pickens showing up just long enough to collect his paycheck in The Swarm, and you’ll get the general idea (although Fierstein, naturally, is doing his standard Gravelly-Voiced Jewish Queer routine rather than Pickens’s equally standard Cartoon Cowboy). Devlin and Emmerich may have started with the premise behind Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, but the execution is nearer to The Towering Inferno, and the resulting film is saved from infernality only by the handful of scenes in which its creators briefly remember what they’re supposed to be doing.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact