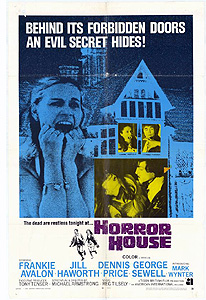

Horror House/The Haunted House of Horror (1969/1970) *½

Horror House/The Haunted House of Horror (1969/1970) *½

Night one of the 2012 Drive-In Super Monster-Rama was unexpectedly brutal. I don’t mean that the movies shown that night were unwontedly gory, grim, or intense, but rather that they weren’t just bad, but bad in that crowd-killing way that regular B-Fest attendees know all too well from the predawn soul-crusher stretch. After the opening film (the superb Theater of Blood), it was a beat-down unlike anything previous years’ programs had prepared me for, until the group I came with fully expected the dawn to find us with Beware! The Blob gloating over our supine bodies, our still-beating hearts clutched in Larry Hagman’s fists. The first audience throat-punch of the evening was thrown by Horror House, a justly forgotten example of Tigon’s ongoing efforts to woo the Swinging London crowd of the late 1960’s, featuring Frankie Avalon in exactly the sort of role that fellow has-been teen idol John Ashley had recently fled to the Philippines to escape.

It’ll be a while, though, before we meet that character, let alone have any reason to pay attention to him. For now, the focus is squarely upon Gary Scott (Mark Wynter), a randy lad whose main point of distinction is to possess even more tragic fashion sense than Alan in Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things. Gary is currently juggling two girls. His official paramour is a bubbly yet prudish blonde called Dorothy Pullman (The Trygon Factor’s Carol Dilworth), whose eye makeup easily matches Gary’s pants for sheer, self-defeating hideousness. The other is Sylvia Fuller (Gina Warwick), older, smarter, and more worldly than her rival. Sylvia knows about Dorothy (the converse is emphatically not true), and she seems understandably annoyed that Gary’s affections are trending in the latter girl’s favor of late. Maybe that’s why Sylvia has been pursuing a dalliance of her own with a much older married man named Bob Kellett (George Sewell, from The Vengeance of She and Journey to the Far Side of the Sun). Whatever her reasons for forming it in the first place, Sylvia has grown weary of her attachment to Bob, and now wishes to break it off. Unfortunately, Bob is not cooperating, and Sylvia is too chickenshit to treat him unequivocally like an ex whenever he comes around offering her rides to places, doing her intrusive favors, and generally stalking the shit out of her.

The reason we need to know about, and must pretend to care about, that silly quadrilateral soap opera is that all four of the participants are present for the event at the center of what passes for the plot, under circumstances suggesting that there might be a connection of some kind. A friend of the kids by the name of Chris (Avalon, whose other rare attempts to do something unrelated to beach parties include Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea and The Million Eyes of Sumuru) is throwing a party, with Gary, Sylvia, and Dorothy all in attendance. Bob manages to browbeat Sylvia into accepting a lift to Chris’s flat, and proceeds to spend the rest of the evening spying on the festivities from outside like a great, big psycho. One of the other guests, a girl named Sheila (Jill Haworth, from It! and Tower of Evil) who is sort of dating Chris in much the same way that Gary is sort of dating Sylvia, quickly loses interest in the gathering, complaining that it isn’t up to the standard she has come to expect of her sometime lover’s parties. She’s got a point, too— I mean, there are no surfboards, no bikinis, and not a trace of Dick Dale anywhere! Sheila’s grousing prompts one of the boys to suggest a change of venue. There’s an old mansion outside of town, supposedly haunted thanks to a family massacre some years back, and breaking in should present no trouble at all. It may not be a beach, but if I learned anything from Quadrophenia, it’s that British beaches are no place for proper recreation anyway.

Chris, Sheila, Gary, Dorothy, and Sylvia are among the group that ditches the original party in favor of ghost-hunting, together with three others: Peter (Richard O’Sullivan, of The Young Playmates), Richard (John Barnes, who later had bit parts in Mars Attacks! and Frankenstein: The True Story), and Madge (Veronica Doran, from The Sex Thief and Escort Girls). And naturally Bob follows along at a discreetly pervy distance when he sees Sylvia taking off in company with no fewer than four other guys. That means that although Kellett doesn’t participate in scouring the mansion for spooks that never appear, or in the séance that never really gets off the ground, or in any of the other things that the kids talk about but don’t actually do, he is there on the premises all night long, stewing angrily over Sylvia. He doesn’t even get an opportunity to pull his usual “Get in the car— I’ll give you a lift” trick, however, for although Sylvia does skip out early and alone on the relocated party, she outmaneuvers her increasingly irritating surplus boyfriend by hitchhiking home instead. So what do you think? Should we conclude the unseen assailant who brings the party to a crashing halt by stabbing Gary to death when he wanders off on his own from the rest of the gang to be Bob, acting out of vengeful jealousy?

Most modern viewers will naturally make certain assumptions about the next hour of Horror House at this point. Spooky house? Pack of teenagers? Stabby maniac running loose in a secluded place? Obviously we’re going to spend the rest of this movie watching six of the remaining eight characters getting carved up one by one, culminating in a fight to the death between the final two. And obviously Bob won’t really be the killer; instead, it’ll be somebody like Peter or Madge— or better yet, Sylvia, since she wasn’t even supposed to be on the grounds anymore when Gary was killed. At first, that does seem to be where Horror House is headed, too. What else are we to make of Chris ludicrously insisting that that none of his erstwhile party guests must leave the mansion until they have figured out which of their number is the killer? As it happens, however, Chris loses his resolve, the murderer refrains from striking again, and everyone eventually disperses with a round of obviously counterproductive vows never to speak of the incident to anyone outside the group.

Yeah, well Gary has a job and a family and friends who weren’t at the mansion on the night of his death, and eventually somebody notices and reports his disappearance. So despite Chris’s best efforts to forestall such a thing, every long-haired young person in London is soon hearing from Inspector Bradley (Dennis Price, from Twins of Evil and Vampyros Lesbos) to answer questions about the missing boy, and that includes Sylvia. True, she left the house before the stabbing, and is therefore in no position to say more than that she hasn’t seen Gary in a while. But her early departure also means that she isn’t in on the conspiracy of silence, and she has no qualms about telling Bradley when and where she and Gary last met. Meanwhile, Bob (who still won’t leave her alone) seems inordinately concerned about the personalized cigarette lighter that she thinks she might have lost at the empty house that night. Those two things might look unconnected, but when Bob sneaks into the mansion himself after dark to go looking for the lighter, somebody stabs him to death, too. Bradley ends up assigned to Bob’s disappearance as well, and he learns from Mrs. Kellett that her husband was having an affair with Sylvia— which makes two missing persons who can be linked in some way to the girl. A return visit with Sylvia reveals the detail about the lighter, which in turn links both of the vanished to the same location. And while that’s going on, Gary’s friends who are in on the cover-up— Dorothy, Madge, and Sheila especially— are rapidly approaching the limit of their endurance for secrecy and paranoia. Their restiveness soon inspires Chris to his most cockamamie idea yet: the gang will return to the scene of the crime to recreate the events leading up to it. As anyone who’s seen Doctor X knows, that will surely compel the killer to reveal him- or herself, and then the others can safely involve the police!

It’s been a long time since I saw a movie as committed to doing nothing as Horror House. What I would normally call the entire first act goes by without ever so much as hinting at the existence of a plot, let alone initiating one. When Sheila fumes about her boredom during the party scene, the audience is all but guaranteed to share her sentiments. Bob, the most useful potential villain, is wasted as a red herring, and is revealed as such when the movie is only half-over. The body-count murders which the film’s premise cues us to expect fail to materialize not only during the first gathering at the mansion, but during the second as well. Bradley’s investigation never amounts to anything, even when the clues point him straight at a chance to catch the killer in the act. Both of Chris’s attempts to lure the killer into the open give rise to more milling around in the dark and complaining than crime-solving worthy of the name, and are hobbled by people shipping out early to do something more productive with their time. The ending gives new meaning to the word “inconclusive,” with the murderer dissuaded from pursuing a victim by his own fear of the dark, and with neither said victim’s decisive escape nor the arrival of the onrushing Inspector Bradley ever depicted. Sheila never even gets her séance in the supposedly haunted house! In short, the beginning of the film sets nothing in motion; the ending brings nothing to a close; and in between, nobody manages to accomplish much of anything they set out to do.

That being the case, what little interest Horror House is able to generate is mostly of an academic nature. For example, a viewer who can muster the necessary attention to detail can see here how Tigon consistently had at least slightly firmer a handle on Britain’s late-60’s youth culture than did their rivals at Hammer and Amicus. The filmmakers don’t do as good a job of articulating the point as they should have, but the kids’ reluctance to involve the authorities is driven by fear that the police will indiscriminately hold them all responsible for Gary’s murder. After all, they’ve all got histories of drug use, and no sensible counterculture type in 1969 would have put it past a cop to take one look at the circumstances surrounding Gary’s death, and immediately think, “Satanic hippy dope orgy ends in acid-addled stabbing.” More importantly, Horror House is basically sympathetic toward its young protagonists’ perspectives. Sure, they smoke pot, drop acid, and drink too much, but that doesn’t stop them from holding down jobs or keeping up with the rent on their apartments. Sure, everyone but Dorothy evinces a sharply dissident understanding of sexual morality, but even Sylvia’s extremely tangled love life is treated non-salaciously, and neither she nor anyone else ever seems to be punished for all their screwing around— unless you count Bob, who is emphatically not a part of the youth culture! And although these kids do dabble in mysticism, it’s a long road indeed from them to Horace Bones and his Mansonesque cult in I Drink Your Blood. Horror House’s creators might not have all the details quite in line as regards the clothes, hair, and music (or maybe they do— I wouldn’t really know one way or the other, since these are British hippies we’re talking about), but they get the underlying ideas shockingly close to right.

The other bit of interest to be extracted from Horror House concerns my age-old fixation, the prehistory of the slasher movie. By 1969, there were several variant traditions within the “loonies with knives” school of horror cinema. There was the ancestral spooky house strain, with its two most important sub-subgenres, the Colorful Killer and Phony Séance categories. There was the original-recipe body-counter, as exemplified by Thirteen Women and And Then There Were None. There was the Diabolique-Psycho-What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? model, with its midstream focal shifts, prosaic settings, and fixation on abnormal psychology. And across the Channel in Continental Europe, there were the Krimi and giallo forms, emphasizing (in different ways and different sets of proportions) visual stylization, bloody violence, and glamorous social milieus. What’s curious about Horror House is that it flirts with all of those approaches, but never settles on any of them. The setup with the ghost hunt and séance in the purportedly haunted mansion is pure spooky house, but that line gets dropped long before any of the associated tropes— the clutching hands, the secret passages, the hidden treasure, the skulking jewel thieves, the inexplicable gorilla in the basement— can come into play. The mob of poorly differentiated characters is normally a clear sign of a body count in the offing, but this killer never works up a sufficient head of steam for that. Killing off Gary after treating him for half an hour as the viewpoint character is a classic post-Psycho touch, as is the motivation for the crimes, which has nothing to do with “rational” considerations like greed or even revenge. However, nothing else about Horror House much resembles a Hammer mini-Hitchcock or a William Castle psycho-horror film. There are hints of the Continental styles, too: the mad killer’s convoluted symptomology, the enviable hipness of the protagonists (or at any rate, what was supposed to be their enviable hipness), the embarrassing ineffectuality of the police. Again, though, those elements aren’t given enough weight for Horror House to feel like a British attempt at making a Krimi or a giallo. Really, this is all just a special case of that overall commitment to doing nothing that I talked about a couple paragraphs ago, but it intrigues me because of the particular things that aren’t getting done. It’s like a bus tour of the genre’s past, driving by all the famous landmarks, but never stopping for a proper visit to any of them.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact