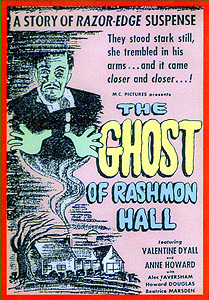

The Ghost of Rashmon Hall/Night Comes Too Soon (1947) -**Ĺ

The Ghost of Rashmon Hall/Night Comes Too Soon (1947) -**Ĺ

The American movie industry all but abandoned horror after 1946, not returning to the genre with any sustained seriousness until 1951, when it was reinterpreted for the most part as a sideline on the emergent sci-fi craze. The intervening years were very much a replay of the late 1930ís, with horror in Hollywood represented almost solely by traces of influence on movies of other types. Film noir and murder mysteries occasionally borrowed the techniques of horror atmospherics or hybridized with traditional horror premises (as in Scared to Death, which canít decide whether it wants to be a modern noir or a 1920ís-style colorful killer flick), but the only straight-up horror movie to emerge from the United States in the four years between The Beast with Five Fingers and The Thing was a roundly ignored mad doctor thing called The Creeper. However, in a truly perverse case of role reversal, Great Britain experienced a short-lived but sizeable horror boomlet at exactly the time when the genre was lapsing into a coma over here. Most of these late-40ís Anglo-horror films saw little or no overseas distribution, and a lot of them were B-pictures so lowly that even the works of Monogram and PRC look lavish in comparison, but a few have earned reputations as extremely minor classics among the handful of fans who know of their existence. On the other hand, some of themó like The Ghost of Rashmon Halló suck magnificently.

There isnít a lot of information about this movie circulatingó which is a shame, because what little is available suggests that the full behind-the-scenes story would be well worth hearing. The Ghost of Rashmon Hall was shot for a pair of undistinguished independent production companies called British Animated Films and Federated Films, originally under the title Night Comes Too Soon. Iím honestly not sure whether that means it represented an attempt by the former firm to branch out beyond their usual niche, or whether Iím just reading too much into the word, ďanimated.Ē In any case, the filmís extreme brevity (the print used for the Sinister Cinema DVD runs 49 minutes, although some sources claim running times as long as 57 minutes) indicates that it would have been intended strictly as a supporting feature, and the resources invested in it were obviously miniscule. The lionís share of the budget probably went to pay for the one name actor in the cast, BBC radio star Valentine Dyall, but he evidently was somewhat less of a draw than producer Harold Baim hoped. In fact, to judge from the very brief accounts in Jonathan Rigbyís British Gothic and Andy Bootís Fragments of Fear, The Ghost of Rashmon Hall may never have received a proper theatrical run at all, moving directly from the trade show and film festival circuit to infrequent airings on British television. The most tantalizing tidbit of all, though, concerns the filmís uncredited writers. If the Internet Movie Database is to be believed, the script was composed by Pat Dixon, working from a story by Edward Bulwer-Lytton. The latter claim is corroborated by an advertising blurb quoted in Rigbyís book, which touts The Ghost of Rashmon Hall as ďa plain down-to-Earth, intriguing ghost story, written as only Lord Lytton knew how.Ē Edward Bulwer-Lytton, of course, is the once enormously popular author for whom the Bulwer-Lytton Awards are named, and Iím sure you can imagine my excitement at the prospect of a movie based on the work of a man whose convoluted, ungainly prose could inspire an annual contest in celebration of bad writing.

Given the Bulwer-Lytton connection, itís rather a shame that The Ghost of Rashmon Hall does not begin on a dark and stormy nightó dark, yes, but not stormy. John (Alec Faversham) and Phyllis (Anne Howard) are having a group of their friends over to their immense country manor for the evening, and Dr. George Clinton (Dyall, whom fans of British fright films can also see in Latin Quarter and Horror Hotel) is running late. Lionel Waddell (Dead of Nightís Anthony Baird), Frank Morley (Howard Douglas, of Stolen Face), Mr. and Mrs. Paxton (Arthur Brander, from Old Mother Riley Meets the Vampire, and Beatrice Marsden), and their hosts pass the time by listening to a ghost story dramatization on the radio, and it is while theyíre discussing what they heard that Clinton finally makes his appearance. The guestsí collective attitude on the subject of spook stories, most forcefully expressed by Morley, seems interestingly enough to be more or less that of the British Board of Film Censors. Although they concede that such tales can be entertaining enough, they find something fundamentally distastefuló even faintly immoraló about amusements that are not grounded firmly in reality, and they worry about the mental fitness of anyone who actually prefers to spend their leisure having their most primitive emotions stimulated. Clintonís rejoinder, Iím certain, is the last one anybody in the parlor expects. He smugly informs Morley and the rest that John and Phyllis have themselves seen ghosts in real life, and that they did so in the very house where they still live. Naturally, everyone wants to hear the story despite all their earlier harrumphing, but John and Phyllis are understandably too embarrassed to tell it themselves. Thus it is that the big-shit radio star gets to spend much of the next 40 minutes or so voiceovering like crazyÖ

John and Phyllis had no easy time finding a place to live when they were newlyweds; one assumes that the Luftwaffe must have left something of a housing shortage in its wake. The couple had to go out into the countryside to find a real estate agent with even one house on offer, and even he (David Keir, from Crimes at the Dark House and The Ghost of St. Michaelís) would admit to having property to broker only after John admitted his desperate willingnes to consider anything at all by way of accommodations. Rather suspicious, if you ask me. The house in question was an 18th-century manse belonging originally to one Rinaldo Sabata, and it had lain vacant for a very long timeó possibly because no one in the last 150 years had wanted to live in a house built by someone so proud of his reputation as a necromancer that he would identify himself as such in his homeís cornerstone inscription. Phyllis did not like the place at all when she saw it (unsavory associations aside, it would need a lot of work to be made habitable), but she and John didnít exactly have a vast array of alternatives to choose from.

They didnít have to occupy their new digs for very long before they noticed the weirdness. Lights in the house cast shadows that were difficult to account for; the door to a section of the house that had not yet been restored would not stay bolted, and could be counted upon to swing back and forth on its hinges all night long; one of the taps would begin dripping as soon as the couple went to bed, only to close itself off come morning. There was also a chorus of whispering voices to be heard by night in the wing beyond the misbehaving door, but never any sign of the whisperers themselves. Most alarming of alló alarming enough, in fact, to make John and Phyllis vacate the house and take a hotel suite in the nearby villageó were the three visible phantoms: a dour-looking middle-aged man (Phantom Shipís Monti DeLyle), an attractive young woman (Nina Erber), and a youth dressed in a sailorís striped blouse (John Desmond).

John was not so terrified as to surrender completely to the supernatural occupancy, however, and he determined to get to the bottom of the haunting. By poking around in the unrestored wing during daylight hours, John turned up a bundle of letters recording an adulterous love affair between the wife of Rinaldo Sabata and a seaman whom Clinton never bothers to name in his narration. Then a trip to the public library brought to light a book called Our Notable County Homes, which contained a chapter on Rinaldo Sabata and his house. According to the book, Sabata caught his wife dallying with the sailor when he returned from a business trip abroad, and murdered both parties. As John explained to Dr. Clinton (now revealed to be something of a paranormal hobbyist) after calling him for advice and assistance, it was his belief that the corpses must be buried somewhere in or around the house. Clinton agreed to spend a night there with John, and if possible to use his expertise to lay the unquiet spirits to rest. The way the two self-made ghost-busters eventually resolved the haunting doesnít make a whole lot of sense, but it makes a great deal more than what Clinton reveals when Morley scoffs at his account. Youíll find yourself wanting to go back and look for Sam Katzmanís name in the opening credits when you see that!

You want a nice, convenient touchstone for how ineptly made this movie is? Okay. The title is The Ghost of Rashmon Halló Rashmon, got that? But the first time we hear the name of Rinaldo Sabataís house spoken aloud, by a crowd of the usual gossiping villagers, they all plainly refer to it as Ramisham Hall. Then the next time Clinton butts in with one of his all-too-frequent storytelling interludes, itís Ramblesham Hall, and when we finally see the name written out in the pages of Our Notable County Homes, itís spelled Rammelsham. Can consistency on so basic a matter as the name of the goddamned setting really be so difficult to achieve? Then again, we probably canít legitimately expect even that much from a movie in which large swaths of the frame are routinely out of focus, and in which the preferred device for skipping over conversations that would convey information we already know is to cut abruptly to several seconds of black screen. There are forms of ineptitude on display in The Ghost of Rashmon Hall that I have seen literally nowhere else, and the filmís more fundamental defectsó like non-sequitur dialogue, near-total plotlessness, and a twist ending demonstrating that the uncredited writerís thought-process does not in any way resemble our Earth-logicó seem rather unremarkable in comparison. But alas, the movie is considerably less entertaining than that makes it sound, primarily because at no point do the ghosts ever actually do anything. They appear, perhaps making a half-hearted attempt at a threatening grimace, and then go away again. The faucet drips, the door to the disused wing swings back and forth indecisively, and thatís pretty much it. Mr. Boogedy is scarier than this bunch! Consequently, The Ghost of Rashmon Hall ends up being pretty fucking boring whenever it isnít actively wowing you with screw-ups and misjudgements.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact